Umm Khaled, who comes from the southern neighborhoods of Damascus, has been living for more than a decade in the shadow of her son’s disappearance. He was only eighteen years old when he was arrested in 2013.

After his arrest, he was taken directly to the Palestine Branch. Four years passed before Umm Khaled found a small thread of hope. In 2017, she obtained a civil registry extract in Damascus confirming that he was still alive, while someone else told her that he was being held in the State Security Branch in Damascus. From that day on, her waiting became an entire life suspended between hope and fear.

At the dawn of December 8 of last year, following the fall of the Assad regime, she rushed to the massive gates of Sednaya Prison north of the capital, holding a photo of her son, hoping she could finally embrace him after his long absence.

But when she arrived that cold morning, amid crowds of people searching for their loved ones, she walked up the road leading to the cells with heavy steps, her eyes filled with hope. The doors opened before her — but her son was not among those emerging from the dark, frigid cells.

About a month later, she visited Sednaya Prison again to attend a commemoration ceremony for the prison’s victims. There, the investigative team met her once more, still holding her son’s photograph, whispering words laden with sorrow as she showed his picture to anyone who might see it — hoping someone might remember him, or might have seen him somewhere inside that prison.

With tears in her eyes, she said: “Unfortunately, my son did not come out alive… Those who survived that prison can be counted on one hand.”

According to Veronica Bellintani, Head of the International Law Support Unit at the Syrian Legal Development Programme (SDLP), execution orders in Sednaya Prison were issued and carried out by secret field committees that provided no minimum guarantees of due process.

She explains: “The executions carried out inside Sednaya Prison clearly fall within the scope of crimes against humanity and conflict-related crimes, given their systematic and widespread nature, and their connection to repressive policies pursued by the Syrian authorities against civilians.”

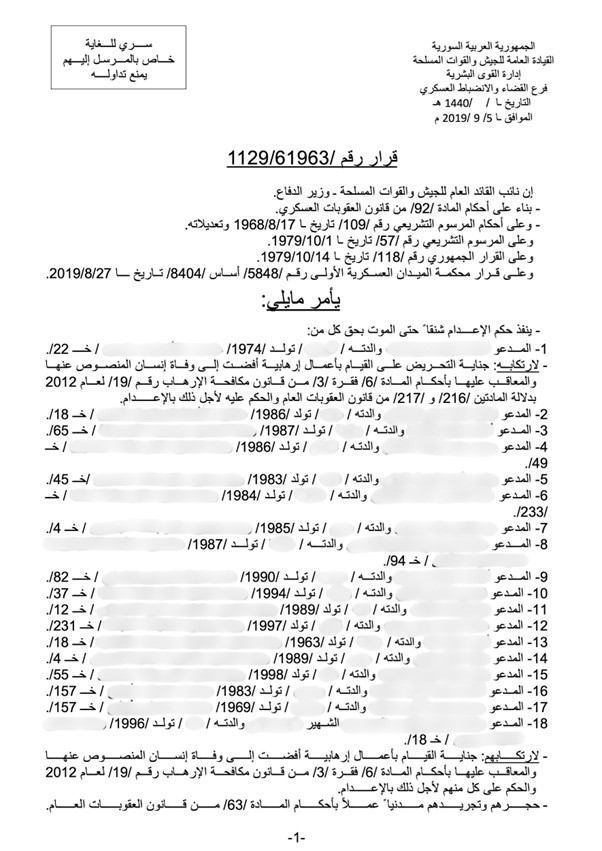

According to information reviewed by the investigative team, at least 15,347 execution sentences were carried out in Sednaya between 2011 and 2021, based on rulings issued by the Military Field Court.

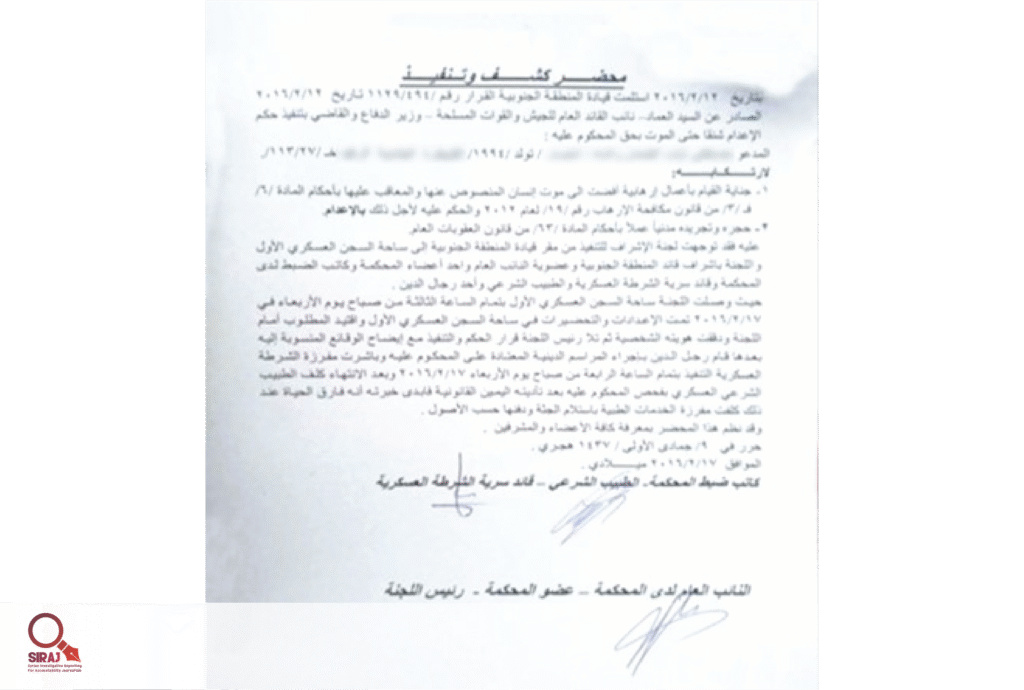

The documents and information reviewed by the investigative team reveal the formation of execution committees whose purpose was to end the lives of prisoners by hanging, with special teams assigned to carry out these executions inside the prison.

On September 16, 2019, 18 detainees lost their lives; they were from Damascus, Daraa, and Aleppo. On September 3, 2020, 29 people were executed, including Tunisians, Iraqis, and Saudis. The gallows were also erected on July 30, November 12, and December 10, 2020, as well as January 19, 2021, to execute groups ranging from four to twenty-eight people at a time.

After the fall of the Syrian regime and the opening of the prison gates, an intense debate emerged among Syrians—especially the families of the victims—about who was responsible for these executions. There has been, and still remains, a strong desire to uncover the chain of command behind the execution orders, and to identify the individuals involved, whose names have long been shrouded in secrecy inside one of the most secretive prisons in the world.

This investigation seeks to answer that question.

Once a death sentence is issued by the Military Field Court, a closed chain of secret procedures begins. According to documents reviewed by the investigation team, these procedures are overseen by what can be described as a hierarchical apparatus composed of two main levels, each with a distinct committee.

At the first level is the “Central Committee”, also referred to as the “Supervisory Committee”, which carries out tasks at the national level on behalf of the state and oversees the general planning and implementation of execution decisions.

At the second level is the “Execution Committee”, which is responsible for carrying out the sentences on the ground inside the prison. Among survivors, this committee is known as the “Chain Committee”, in reference to the chain used to bind the victims’ legs as they are led to the execution chamber to meet their fate.

Orders establishing these committees are issued by the commander of the First Military Prison— the official designation for Saydnaya Prison— whose approval appears only in the form of a signature, without a name.

After reviewing the formation orders of the named committees and examining them, the SIRAJ unit assembled a team to track members of the two execution committees listed in the documents, using analysis of official records, cross-referencing survivor testimonies, and open-source intelligence techniques.

The investigation team and the open-source unit were able to trace 27 individuals whose names appeared in the documents. Some of them remain inside Syria, while others are believed to have left the country.

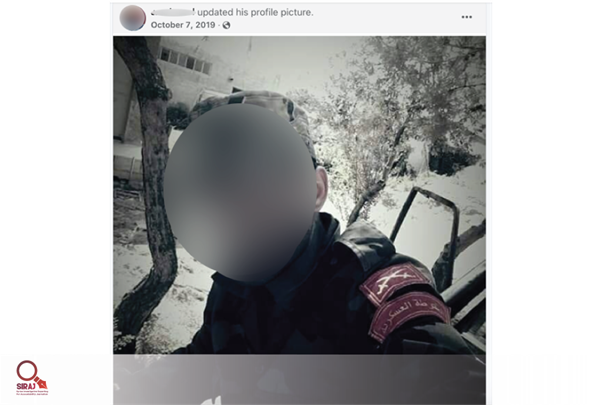

In addition to the names of the execution committee members, the information collected includes: their dates of birth, social media accounts—particularly Facebook—photographs of them in both military and civilian attire, and images showing them with well-known figures associated with Saydnaya Prison. Some were previously photographed alongside Aws Salloum, known by the nickname “The Angel of Death of Saydnaya.”

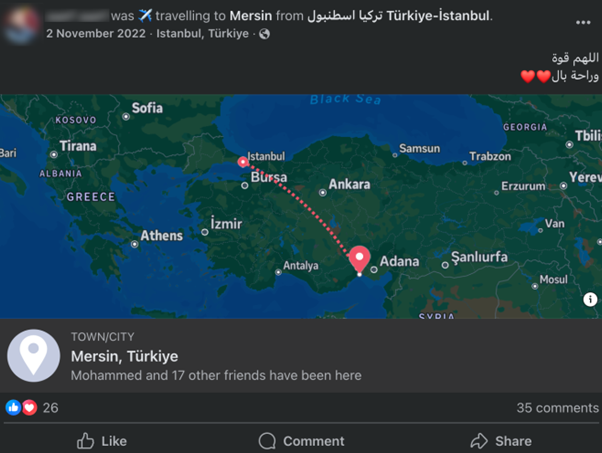

One member of the 2020 execution committee (the “Chain Committee”), identified as “Ahmad A.”, is currently residing outside Syria and moving freely within Turkish territory.

On his Facebook account, he shared a post showing that he traveled from Istanbul to the southern city of Mersin on November 2, 2022.

He also appears in photos he claims were taken at the port of Odesa, Ukraine, on October 18, 2022. Before that, on September 20, 2022, he asked his friends and followers to wish him success on a trip to Egypt. Earlier posts show him in military uniform, wearing the Military Police insignia on his arm, inside the prison grounds.

Many other photos show members of the execution committees in their everyday lives— sitting in cafés, at private gatherings, or on the beach —while others are engaged in different professions. One example is a dentist who now works at a charitable association in the village of Beit Yashout in Latakia province, offering free medical services.

The investigation team worked to cross-match the names and images of members of the two execution committees across a wide range of open sources, despite their dispersion and differing natures, in order to accurately verify the identities of the individuals.

To strengthen the verification process, the team consulted Syrian researcher Hussam Jazmati, who spent years documenting the social media accounts of officers and personnel at Saydnaya Military Prison, including several members of the execution committees.

Jazmati maintains a well-documented archive that intersects with the work of Syrian organizations specializing in the cases of detainees and their families. A comparison between his findings and those of the investigation team showed a 100% exact match in names and photographs.

In addition, we contacted a military doctor whose name appeared in one of the execution committees under investigation. He was able to identify the faces and names of many of the other committee members—his colleagues—on the same committee.

This testimony, being the first of its kind, served as a final and decisive confirmation for the investigation team in verifying and identifying the members of the execution committee.

“In Absolute Secrecy”: The Structure of the Execution Committees

The investigation into the execution committees began when the team obtained copies of official documents indicating the formation of a supervisory committee responsible for carrying out execution rulings. The committee was composed of at least three members:

The Deputy President of the Military Court, a forensic doctor, and an officer from the Military Police.

Executions at Saydnaya Prison are carried out on a weekly basis. Between 20 and 50 detainees are taken to the gallows without prior notice; they are not informed of the execution date. Instead, they are transferred at night and executed either that same night or early the next morning, before dawn.

The operation is overseen by senior security and military officials, including the head of the prison’s security office, the prison director, the military prosecutor of the Field Court, the commander of the Syrian Army’s Southern Region, an officer from the Military Intelligence Directorate, and the head of Branch 248 (the Investigations Branch), in addition to a forensic doctor from Tishreen Military Hospital. In some cases, a religious cleric is brought in to provide a veneer of religious legitimacy to the executions.

This committee handles the official (state) supervision of the executions, documenting the process and confirming the deaths, all in the absence of any independent oversight or civilian legal supervision.

The actual execution is carried out by the Execution Committee at 4:00 a.m., inside the First Military Prison building.

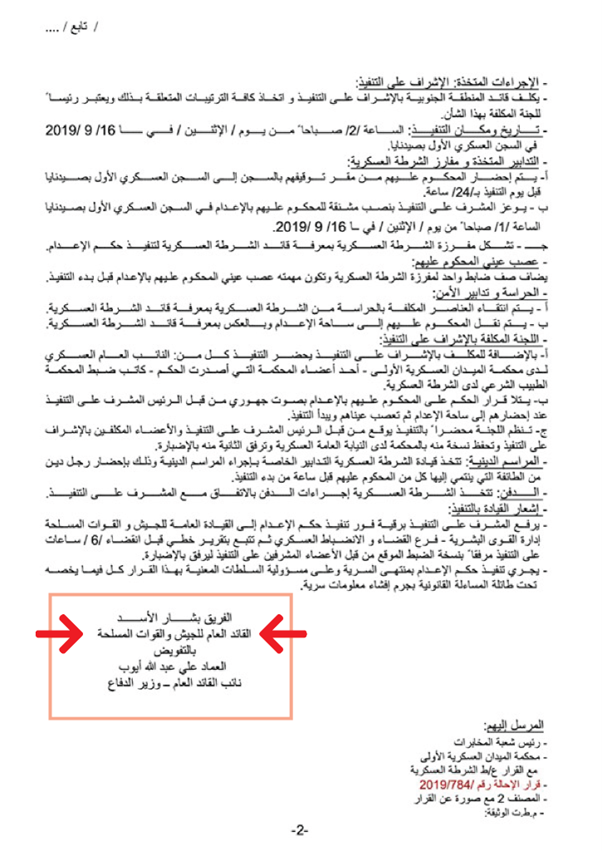

The execution report is then submitted to the Command of the Southern Region of the Syrian Army, with an explicit note stating that it is carried out “based on the order of the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Minister of Defense.” This indicates that the orders are not local, but are directly tied to the leadership of the regime—and therefore to Bashar al-Assad himself.

Marwan Al-Ash, from the Syrian Detainees and Detainees’ Council (SDC), explains that executions are carried out in a routine, rigid, and highly secretive manner. The names of those to be executed are summoned by the judge of the Military Field Court, following a chain of approvals that begins with the Director of the Military Judiciary and ends with the Minister of Defense acting on behalf of the President. This process applies to Syrian, Arab, and foreign detainees alike.

Convicts are separated from the rest of the prisoners 48 hours prior to execution and transferred to an “isolation room” in the Red Building, where they are deprived of food and subjected to intense torture. Later, the group is transported at night to the White Building in a closed truck, under violent procedures that include beatings, blindfolding, and shackling with chains.

According to Al-Ash: “Executions are carried out by hanging, in batches of seven. The bodies are suspended and then dropped, and left in a side room, sometimes for days, before being moved to the prison’s outer courtyard to await a truck or refrigerated vehicle that transports them to mass graves.”

From Blindfolding to the Noose

All documents issued by Saydnaya Prison regarding execution orders contain the same directive: that executions must be carried out under strict secrecy.

Each document specifically names an officer or assistant tasked with carrying out the order, with explicit instructions emphasizing absolute confidentiality.

Secret documents from Saydnaya Prison from 2019 and 2020 list dozens of officers and conscripts, each assigned precise duties within the execution system.

Each committee consists of between 14 and 16 guards and commanding personnel. Their duties include: blindfolding prisoners before removal from their cells, fastening restraints, confirming identities, preparing the execution chamber and the noose, and medically documenting the death.

Often, the documents identify an officer or assistant assigned to “carry out the order in complete secrecy at the specified time and place.” They are signed by the Director of Saydnaya Prison and countersigned by a junior military doctor serving on the committee.

Although the identity of the prison director is often obscured, numerous sources—including the Syrian Network for Human Rights—indicate that the directors of Saydnaya Prison during 2019–2020, the period covered by the documents obtained by the investigation team, were Colonel Wasim Suleiman Hassan, followed by Brigadier General Osama Mohammed Al-Ali.

Colonel Wasim Hassan, from rural Latakia, served as prison director from 2017 until 2020, when he was replaced by Brigadier General Osama Al-Ali, from rural Tartus, who remained in the position until the fall of the Assad regime.

In one order dated January 16, 2020, the name “Assistant Yazan M.” (listed in the execution documents) appears as the individual tasked with blindfolding detainees before execution. In another document, the signature of “Amer T.”, a dentist, appears in his capacity as the medical officer accompanying the execution committee.

Regarding leadership responsibility, Belintani explains that “execution orders signed by senior officials, bearing their names and signatures, may constitute strong evidence of their knowledge of the executions, their contribution to the criminal process, and the existence of a systematic policy behind these acts.” This, she says, could therefore allow for their criminal liability under international criminal law.

From the Death Chamber to Television Screens

Each execution committee is assigned, by order of the prison director, the task of carrying out death sentences—though individual roles may vary.

For example, assistants “Mudar A.” and “Yazan M.”, according to the official formation orders of the execution committees in 2019 and 2020, were tasked with blindfolding detainees prior to mass executions.

However, Mudar A. also had an additional role: he was responsible for receiving the bodies of executed detainees when they were returned from military hospitals.

The investigation team reviewed three documents listing execution committees for 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively, and found several repeated names, indicating a stable structural pattern in how personnel were assigned.

Among the recurring names are conscript “Mohammad M.” and sergeant Ramadan Al-Issa, both of whom appeared on multiple committees. Al-Issa recently appeared in a video released by the Syrian Ministry of Interior, in which he confessed to crimes committed during his service in Saydnaya Prison.

The documents also reveal promotion pathways for some committee members, suggesting a direct link between participation in executions and career advancement. For instance, “Yazan S.” served as a corporal on the 2019 and 2020 execution committees, before being promoted to sergeant and appearing again on the 2021 committee.

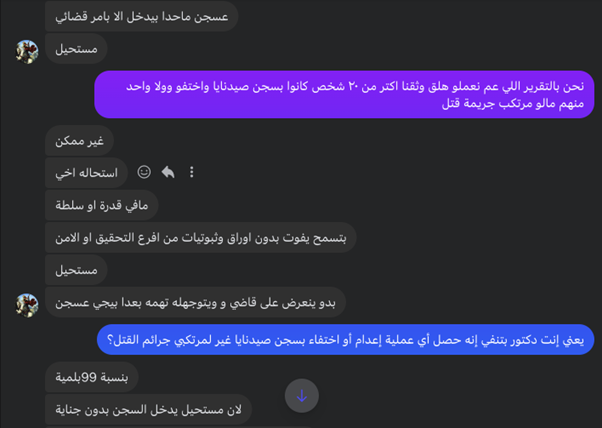

The investigation team contacted 12 members of the execution committees via messaging platforms such as Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp to verify their identities and confirm their roles.

Conscript “Amjad A.” denied his identity entirely, claimed to be someone else, then blocked the reporter on Facebook and changed the name of his account.

The second individual who responded was Lieutenant Dentist “Amer T.”, whose name appears on the 2020 execution committee.

Another member, also a dentist whose name appears on the 2019 committee, also responded and provided critical acknowledgements, on the condition that his name not be disclosed.

Both doctors stated that they were performing compulsory military service at Saydnaya at the time. They also said they contacted the new Syrian authorities immediately after arriving in Damascus.

The first doctor, Amer T., denied that his role involved examining bodies after execution. Instead, he claimed his task was only to examine the health condition and readiness of military personnel involved in the execution process, not the detainees themselves.

The doctor whose name appeared on the 2020 execution committee confirmed that he was serving his mandatory military service as a dentist at Saydnaya Prison. Although he insisted that he was “not allowed to know any information regarding the implementation of executions,” he nevertheless provided detailed accounts of the military personnel on the execution team whom he examined and recognized from photographs. He recalled all of their identities, including First Assistant “Diaa A.”, Corporal “Yazan S.”, conscript “Ahmad A.”, conscript “Mohammad M.”, conscript “Elias H.”, and conscript “Zakaria H.”. He also identified additional individuals involved in the executions, such as conscript “Khedr Q.” and “Hayan D.”

(All of these names were listed in the official documents that formed the execution committee.

He explained that, to his knowledge, executions were carried out in the presence of personnel from Military Intelligence, the regional military commander, judges from the Military Field Court, and a forensic doctor from the military hospital.

When asked how he felt about examining military personnel prior to executions, he said: “I did not choose to be in that place, and if I had been given a choice, I would not have accepted it. Of course, it was disturbing, but I cannot speak of regret because a doctor is supposed to serve the community away from chaos — especially since I did not know the crime committed or the circumstances of the case.”

He claimed that death sentences were only carried out in cases of murder, while what he described as “ordinary violations” resulted in fixed prison terms or, at times, pardons.

However, dozens of documents signed in the name of the Commander-in-Chief (Bashar al-Assad) show that most of those executed were civilians arrested on security-related grounds, including students, women, and former conscripts, contradicting the testimony of Amer T.

A document reviewed by the investigation team from the Syrian Revolution Archive reveals an order issued by former Defense Minister Ali Abdullah Ayoub, acting on behalf of Bashar al-Assad, to execute 18 individuals on charges of “incitement to terrorism” or “committing terrorist acts,” with the executions to be carried out in Saydnaya Prison. The document details the full structure and procedures of the execution process — and is one of many examined by the investigative team.

The dentist also denied that any political detainees had been executed in Saydnaya Prison, claiming that he was “99% certain” that those who were executed had committed murder or “horrific massacres.”

He continued defending Saydnaya’s practices, stating: “It is impossible for anyone to be admitted to the prison without a judicial order.”

When asked about the families who lost their children in Saydnaya—families who dug through the prison grounds searching for their loved ones after the fall of the regime—he attributed this to “misleading media propaganda,” insisting that “it is impossible for anyone to be imprisoned without having committed a crime.”

He added: “Political detainees may have disappeared in security branches,” noting that political detainees are tried in civilian courts, where—according to him—no violations leading to execution occur.

This claim ignores well-documented facts and reports issued by human rights organizations and United Nations bodies confirming that thousands of political detainees in Syria were subjected to summary trials before Military Field Courts or the Counter-Terrorism Court, without due process, and that their families were never informed of their deaths. No national or international entity was allowed access to Saydnaya or other prisons of the former regime until its collapse.

This is also emphasized by Syrian lawyer Hala Ibrahim, a member of the Syrian Free Lawyers Association, who has been closely following the Saydnaya executions while working with a rights organization in Syria. She stresses that the rulings issued by the Military Field Court violated not only international law, but also the Syrian Constitution in force at the time, which guaranteed the right to a fair trial in Article 28—conditions entirely absent from these show trials, which relied on confessions extracted under torture.

For his part, dentist Amer T. told reporters that three days after Syria was liberated, he was contacted by the “Military Operations Directorate” for information regarding the prison’s layout. He claimed that he cooperated, providing them with full details, and explained that he was a conscripted doctor serving mandatory service at Saydnaya. He added, “Brigadier Abu Khaled contacted me from a private number and asked for help to determine whether there were secret tunnels inside the prison. They assured me of my safety, and I explained the structure to them. They also offered me financial compensation for the information, but I refused.”

For its part, the Syrian Ministry of Interior denied the dentists’ statements about their alleged communication with the “Military Operations Room” after the fall of the regime, calling their account “false,” intended to defame the government and evade responsibility for violations.

Ministry spokesperson Noureddine Al-Babba stated: “The number of those implicated in the violations at Saydnaya Prison reaches into the hundreds, and the Ministry is working to bring all of them to justice. We are exerting all efforts to apprehend those involved.”

He added that some have not yet been brought to trial because they are either in hiding inside Syria or have fled abroad, noting that many others are currently detained pending further investigation.

In the same context, lawyer Hala Ibrahim believes that the transitional government’s approach to accountability and transitional justice remains framed through a political or security lens. She stresses that this file requires a comprehensive legal and rights-based approach, making clear that accountability is not an act of revenge, but a legal process in the interest of Syrian society.

The second doctor at Saydnaya Prison, whose name appeared on the execution committee formed in 2019, hesitated to speak with us for weeks before eventually agreeing—on the condition that his name not be published, out of fear of extrajudicial killings. He explained that he was “a doctor for judicial detainees, performing mandatory military service.”

He clarified that his role in the execution committee began after the sentence had already been carried out.

According to him, the Military Medical Services Administration transported the bodies from the execution chamber to the small clinic where he worked inside Saydnaya Prison, so that he could “check vital signs” and confirm death.

He began his service at Military Hospital 601 and was later transferred to Saydnaya.

He stated, “I confirmed the deaths of people who had been executed by hanging twice. The first time was a group of 17–18 detainees brought to me after the execution. I simply confirmed their deaths, and then the Medical Services Administration handled the burial.”

The second case involved a civilian prisoner convicted of murder and rape under a civilian court ruling. He noted that civilian death sentences were also carried out in Saydnaya Prison.

He explained that during executions, a committee from outside the prison would be brought in to carry out the hanging, while the Medical Services Administration was responsible for the execution and burial procedures, “after presenting the executed individuals to me to confirm death.”

He emphasized that people from outside the prison were present during the executions, underscoring the role of the supervisory committee.

He added, “I spent a year in Saydnaya. The execution system had been in place for ten years.”

The doctor described himself as “the lowest-ranked person in a large military hierarchy,” stating that he only received orders to confirm death and that his role came after the execution had already taken place.

Execution Battalions Led by Doctors

On May 1, 2021, what became known as “execution battalions” were formed inside Saydnaya Prison. Each battalion consisted of eight members, including an assistant named “Iyad A.” and a doctor assigned to supervise executions named “Lujain M.” The mention of the doctor is particularly significant: documents reviewed in cooperation with Zaman al-Wasl do not refer to forensic doctors, but rather to specialist physicians—such as ophthalmologists or dentists—who were brought into execution teams. This raises serious questions about the nature of the role they were expected to play.

A document dating back to 2022 concerning “financial rewards” for members of these battalions reinforces the credibility of their existence and function within the prison. Records indicate that in 2021 alone, more than eight execution battalions were formed in Saydnaya, involving approximately 90 individuals—officers, soldiers, and doctors—some of whom were brought in from the Military Police outside the prison to accommodate the high volume of executions.

However, according to Veronica Belintani of the Syrian Legal Development Program: “Medical personnel who participate in documenting, facilitating, or supervising executions bear criminal responsibility under international criminal law.”

She adds:“Their involvement—whether active or passive—may lead to individual liability for war crimes and crimes against humanity, depending on the circumstances of their participation.”

The Execution Platform

On the morning of December 8, a young man named Ghazi Al-Muhammad was scheduled to be executed alongside 54 other detainees inside Saydnaya Prison. But just hours before the sentence was carried out, the prison garrison fled following the collapse of the regime and Bashar al-Assad’s escape to Moscow. Ghazi survived the execution, while the gallows had already claimed the lives of thousands before him.

And although Ghazi was given a second chance at life, thousands before him were not as fortunate. Among them were the brother of Hayat Al-Turki and five of her relatives. Despite spending four days inside Saydnaya after the prison was opened—searching desperately for any trace of them—she found nothing. She believes they were executed.

What she found instead was silence, emptiness, and the remnants of those who died without a witness and without a grave.

The escape and disappearance of members of the execution committees—those responsible for the killings of hundreds of prisoners—have shattered Hayat’s remaining hope of learning the fate of her loved ones, or of seeing their jailers held accountable during Syria’s transitional justice process.

Inside the Execution Chamber at Saydnaya

The investigation team was able to inspect what is known as the “execution chamber.” The room is located on the lower level of what is referred to as the “White Building” within the Saydnaya Military Prison complex, specifically behind a burned door overlooking the southeastern courtyard of the facility. Its entrance leads to a short staircase of three or four steps, opening into a narrow corridor lined with small cells that once held prisoners awaiting execution.

At the end of the corridor lies the main chamber, which over the years was transformed into a site of mass hangings. Burn marks are still visible on the walls and on the metal bunk beds. Two wooden platforms used for executions remain in place, each preceded by a short set of three steps — exactly as depicted in the architectural diagrams documented by international human rights organizations.

Field evidence indicates that prisoners were led onto these platforms to be suspended from the ceiling, where executioners would pull down on their bodies to accelerate death by breaking the neck. Charred markings and remnants of metal execution ropes attest to the intensive use of the room, which now stands as a silent witness to one of the most systematic and brutal episodes of violence in the prisons of the former Syrian regime.

When Will the Execution Squads Be Prosecuted?

In 2017, a report by Amnesty International documenting mass executions and extermination at Saydnaya Prison concluded that the bodies of detainees who were executed or who died under torture and in inhumane detention conditions were buried in mass graves. One of these sites was visited by the investigation team after the fall of the regime in December 2024.

The executions and enforced disappearances were not isolated acts, but rather a systematic policy overseen by the highest levels of the Assad regime’s security and military leadership.

Fadel Abdul Ghany, director of the Syrian Network for Human Rights, states: “These crimes require international legal accountability under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, as they constitute crimes against humanity and war crimes.”

Regarding the possibility of prosecution, Veronica Belintani emphasizes that: “Universal jurisdiction allows European states to prosecute perpetrators even if the crimes did not occur on their territory, provided sufficient evidence exists and the suspects are within their jurisdiction.”

All official documents related to execution orders were signed by Field Marshal Bashar al-Assad as Commander-in-Chief, and delegated to General Ali Abdullah Ayoub, Minister of Defense. According to international legal experts, this constitutes prima facie evidence of the leadership’s knowledge of, and direct involvement in, the executions.

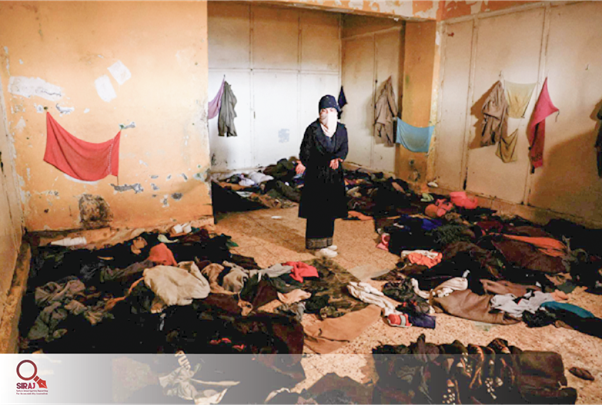

Refrigeration Room and Mass Graves That Swallow the Evidence

In the dim corridor leading to the refrigeration room on the prison’s lower level, the personal belongings and clothing of detainees are scattered alongside used military blankets. Orange execution uniforms in various sizes—small (S), medium (M), and large (XL)—are strewn across the floor, in the corners, and on the metal steps leading into the chamber.

When the investigation team visited the site in February, the cold winter air added an extra layer of chill to the atmosphere of the refrigeration room, which had been hastily constructed inside the prison to cope with the rising pace of executions and the accumulation of bodies.

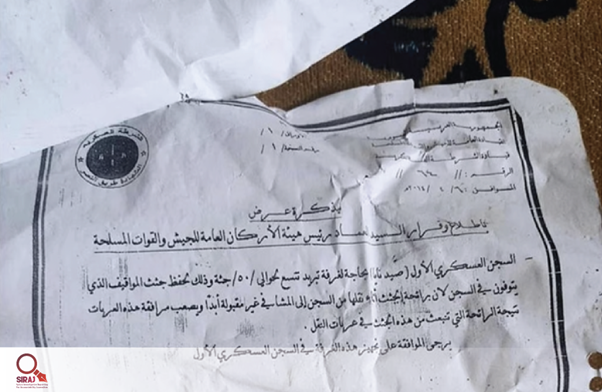

A “request memorandum” issued in April 2014 by the Military Police Commander, Major General Akram Salloum Al-Abdullah, shows a request to establish a room for storing the bodies of deceased detainees inside the prison, with a capacity of no less than fifty bodies, due to difficulties in transferring them to hospitals.

The memorandum was submitted directly to the Chief of Staff at the time, General Ali Abdullah Ayoub, who signed it with approval, indicating once again that senior leadership was aware of these practices — and authorized them.

Aya Majzoub, Deputy Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International, states: “Extrajudicial executions and killings carried out through summary procedures constitute grave violations of international human rights law, and may amount to crimes against humanity when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population, pursuant to a state or organizational policy to carry out such an ‘attack’ or to further that policy.”

According to Amnesty International, the application of the death penalty in Syria violates international human rights standards, specifically Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which restricts the death penalty to “the most serious crimes” and requires that it only be imposed following a fair trial.

By examining official documents from Saydnaya Military Prison, the Syrian Detainees and Detainees’ Councilconcluded that the number of death sentences carried out inside the prison against detainees from the revolution reached 15,347 executions, issued solely by the Military Field Court and the Counter-Terrorism Court—not including deaths resulting from torture, medical neglect, or disease, which are estimated to be several times higher.

Rituals of Mass Death

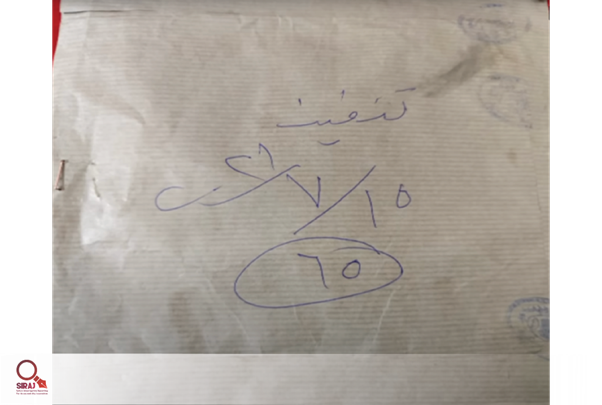

Mohammad Fares and Adnan are among eight former prisoners interviewed by SIRAJ who were released from Saydnaya. Fares provided the investigation team with a list of 65 individuals executed in July 2021.

Fares was sentenced to death without ever appearing in court.

He says: “I survived execution only after my family paid $100,000 to have the sentence reduced to life imprisonment.”

He adds:

“Everything in Saydnaya Prison was for sale — even lives.”

Marwan Al-Ash, a member of the Syrian Detainees and Detainees’ Council, explains: “Everything is carried out under strict secrecy. Bodies are not returned to families, and no burial ceremonies are allowed. Death is recorded on paper, and the bodies are buried in the ground without a trace.”

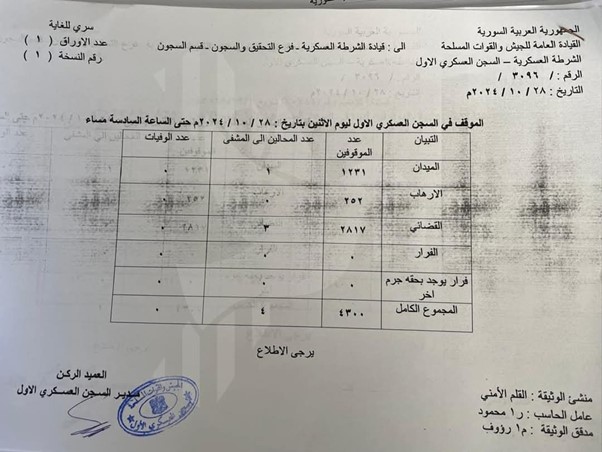

According to Al-Ash’s estimates, 300,000 people were forcibly disappeared for security-related reasons in Syria between 2011 and 2024. Around 90,000 detainees are believed to have entered Saydnaya Prison, while no more than 4,200 are estimated to have survived.

Media advisor at the National Commission for the Missing, Zeina Shahla, explains that the Commission does not yet have consolidated estimates regarding the number of missing persons in the prison, as it is still in the early stages of establishing its foundational framework. She notes that the Commission is responsible for uncovering the fate of the missing across all detention sites—including Saydnaya—using documents, collective interviews, and various documentation methods.

In May of last year, the new Syrian government established a state-level National Commission for the Missing, an independent Syrian body tasked with determining the fate of tens of thousands of disappeared and forcibly disappeared individuals in the country, and ensuring justice for their families.

The Hidden Role of Doctors in Concealing Evidence

The violations against victims of execution at Saydnaya did not end when they fell from the gallows. The abuse continued after death, through a complex system designed to hide the truth and erase identities. After executions, the bodies were transferred to military hospitals, where they were reduced to numbers in official registers that concealed the real crimes.

Official documents reviewed by the investigation team reveal the involvement of doctors and officers at Tishreen Military Hospital in Damascus in receiving dozens of bodies transferred from security branches and prisons. They routinely recorded false causes of death, such as “cardiac arrest” or “heart failure,” while the true cause was execution by hanging.

One of the key figures appearing in the documents is Brigadier General Dr. Ismail Jadallah Kiwan. Documents covering a period of less than four months in 2016 show that he received more than 82 bodies of detainees and recorded the cause of death in almost all cases as “sudden cardiac arrest.”

The documents also show that, in the same period, Kiwan received 746 detainees in critical condition due to torture, most of whom remain unaccounted for. Given that these documents represent only a small window within his 14-year tenure, sources estimate that the total number of detainees and bodies he handled could exceed 10,000.

Kiwan’s role was not limited to Tishreen Hospital. The documents also link him directly to the numbering of bodies at Military Hospital 601, one of the central facilities for receiving and processing the victims of torture in Damascus.

With the fall of the regime on December 8, 2024, Kiwan fled the hospital, leaving behind a record saturated with evidence of systematic medical complicity in one of the most extensive, organized efforts to conceal crimes in modern Syrian history.

The investigation team examined the logbook of Tishreen Military Hospital in Damascus, which contains lists of detainees transferred from security branches. Next to the name of each detainee who arrived deceased, only the word “body” (جثة) was written—without any reference to the cause or circumstances of death—reflecting a deliberate attempt to erase evidence and conceal the truth.

The records also included the names of several doctors and nurses suspected of involvement in these procedures, including the hospital director Moufid Darwish, forensic doctor Akram Al-Shaar, and other medical and administrative personnel who either documented the cases or supervised the receipt of bodies.

Contributors:

Omar Al-Bam contributed to this investigation

Creative coordination and visual design: Radwan Awad

The editorial team at SIRAJ has withheld the full names of members of the execution squads at Saydnaya Prison, and faces have been blurred, in order to protect the public interest and prevent any extrajudicial retaliation, in line with the principles of transitional justice in Syria.