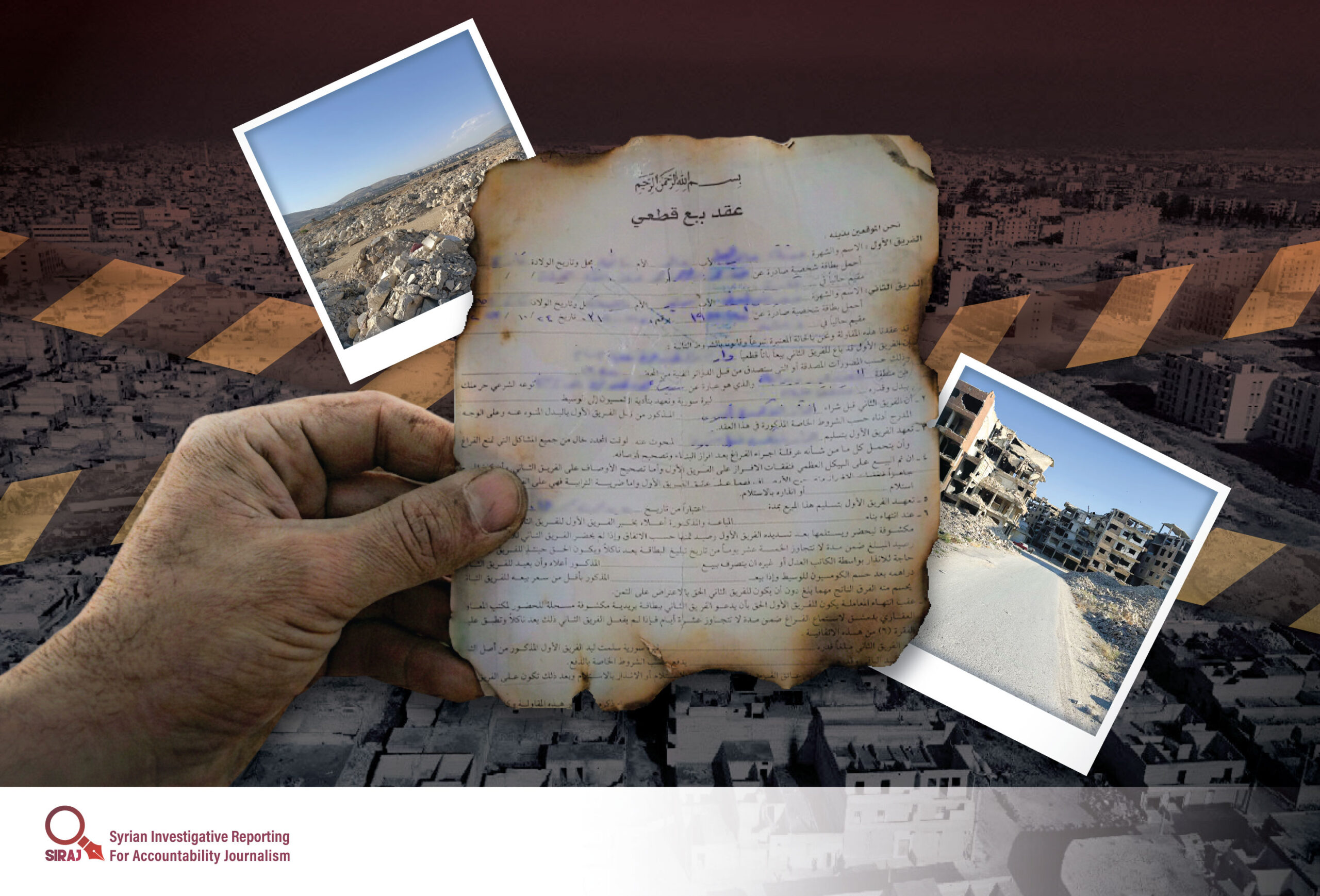

More than 13 years after the attack on the media center in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, Syria, which resulted in the killing and injury of international journalists, new evidence has emerged confirming that the attack was not random shelling but a targeted operation against the media center and its journalists.

The attack resulted in the death of American journalist Marie Colvin and French photojournalist Rémi Ochlik, and it injured French journalist Édith Bouvier and British photographer Paul Conroy. Several Syrian journalists and media workers, including Syrian translator Wael al-Omar, activists Bassel Fouad, Abbad al-Soufi, and others, also sustained injuries.

Marie Colvin, the war correspondent born in January 1956 in New York City, worked for many years with the British newspaper The Sunday Times and reported from some of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones. She was widely recognized for her exceptional courage and her ability to penetrate front lines that others could not.

New evidence published for the first time in this investigation strongly supports years-long claims that the Syrian regime deliberately targeted the media center after identifying the journalists who were inside.

The evidence not only shows that Syrian regime officers had prior knowledge of the journalists’ presence inside the center at the time it was attacked, but also refutes claims made by former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in an interview with the American NBC News TV that his forces had no knowledge or intention to kill Colvin.

Before the strike, the regime created detailed intelligence plans to ensure the attack’s success in killing everyone inside the center, including both Syrian and foreign journalists.

The findings further confirm that the artillery shelling of the media center in the Baba Amr neighborhood constitutes a war crime, based on the documented preparatory actions carried out by Assad’s officers in the area. Based on numerous credible witness accounts and expert analysis, the investigation also identifies with a high degree of certainty the type of artillery shell used, its launch location, and its trajectory.

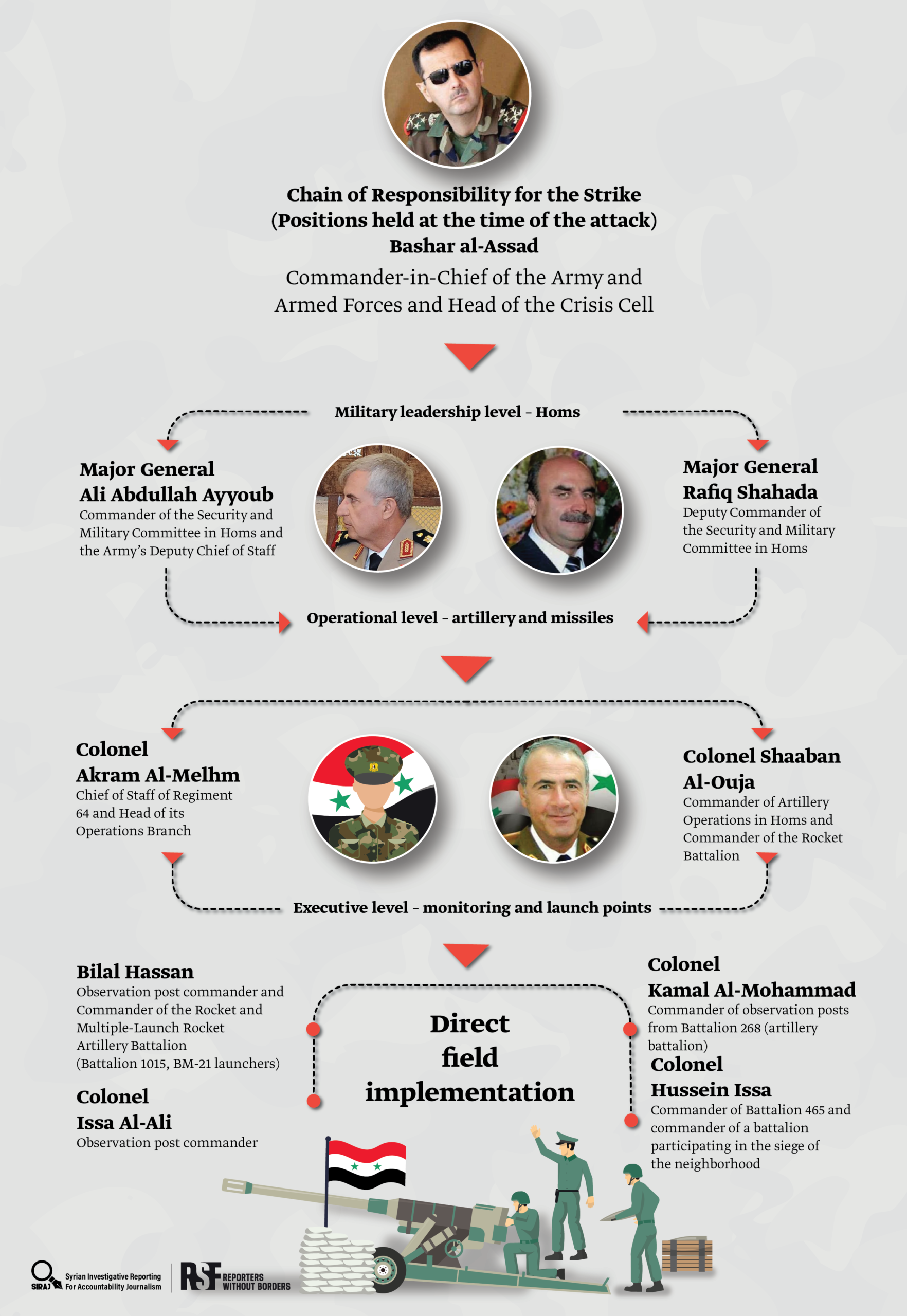

This investigation establishes a clear chain of responsibility for the strike, involving multiple officers within the Assad regime ranks who approved the attack before it was executed with high precision. It traces the chain of command all the way to the top of the administrative and military hierarchy within the regime’s army.

The evidence also includes information and testimonies indicating the existence of surveillance and monitoring mechanisms targeting the media center, as well as monitoring the conditions surrounding the evacuation of the injured journalist Édith Bouvier from the besieged area, after she refused to leave through humanitarian corridors controlled by the Syrian regime.

These materials were compiled as part of a lawsuit led by the Syrian Free Lawyers Association and a group of French lawyers before the War Crimes Court in Paris. The investigation team reviewed the documents and files that contributed to this investigation.

The conclusions establishes that the attack on the media center in Baba Amr “was not random, but rather premeditated and carried out with the aim of eliminating the presence of journalists in Homs to prevent coverage of the Syrian regime’s deadly attacks, and to instill fear among journalists to deter them from entering Syria to cover the conflict from opposition-held areas,” according to a statement sent to the investigation team from the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), a Paris-based human rights organization closely following the case.

Tracking Before the Strike

In 2001, Colvin lost her left eye while covering the civil war in Sri Lanka after being hit by shrapnel from a shell. The injury did not end her career; instead, the black eye patch she wore became a symbol of her determination to continue reporting.

At the start of the Syrian uprising in March 2011, Colvin set her sights on Syria. Although the Syrian authorities denied her an official entry permit, Colvin, who had never known retreat, was determined to reach the country and expose what was happening on the ground, regardless of the cost. She arranged to cross the border from Lebanon, heading to Homs—one of the first cities to come under heavy bombardment and a central hub of protests against the regime.

Colvin arrived in the besieged neighborhood of Baba Amr and took shelter with other journalists and activists in a building that had been turned into a makeshift media center. There, she spent days closely witnessing the suffering of civilians: hunger, cold, and the constant fear of shelling that never ceased. These scenes, which she documented in her final reports, became the testimony that placed her at the heart of danger—later turning into the final chapter of both her professional and personal life.

On February 21, 2012, one day before the media center was shelled, Colvin and her colleagues visited civilian areas that had been bombarded by the regime, resulting in the deaths of many civilians, including women and children.

In the midst of the shock she experienced upon seeing a dying child, Colvin went live on TV from inside the Baba Amr media center. She described civilian casualties, the terror engulfing the neighborhood’s residents, and the catastrophic conditions in local hospitals.

Marie bravely broadcast live using satellite technology in an environment overwhelmed by the regime’s spying drones, telecommunications jamming, and networks of informants, but the regime was able to locate the signal. She did not realize that this broadcast would be her last.

On this night, French journalist Édith Bouvier arrived in Baba Amr, unaware that the next morning, the media center would be targeted and she would be inches from death while witnessing the deaths of Colvin and Ochlik.

Yasser Shalti, a specialist investigator in war crimes and crimes against humanity, led the investigation and evidence-gathering in the case concerning the targeting of the media center in the Baba Amr neighborhood. The lawsuit was filed against the Syrian regime before the War Crimes Court in Paris, leading to the issuance of arrest warrants.

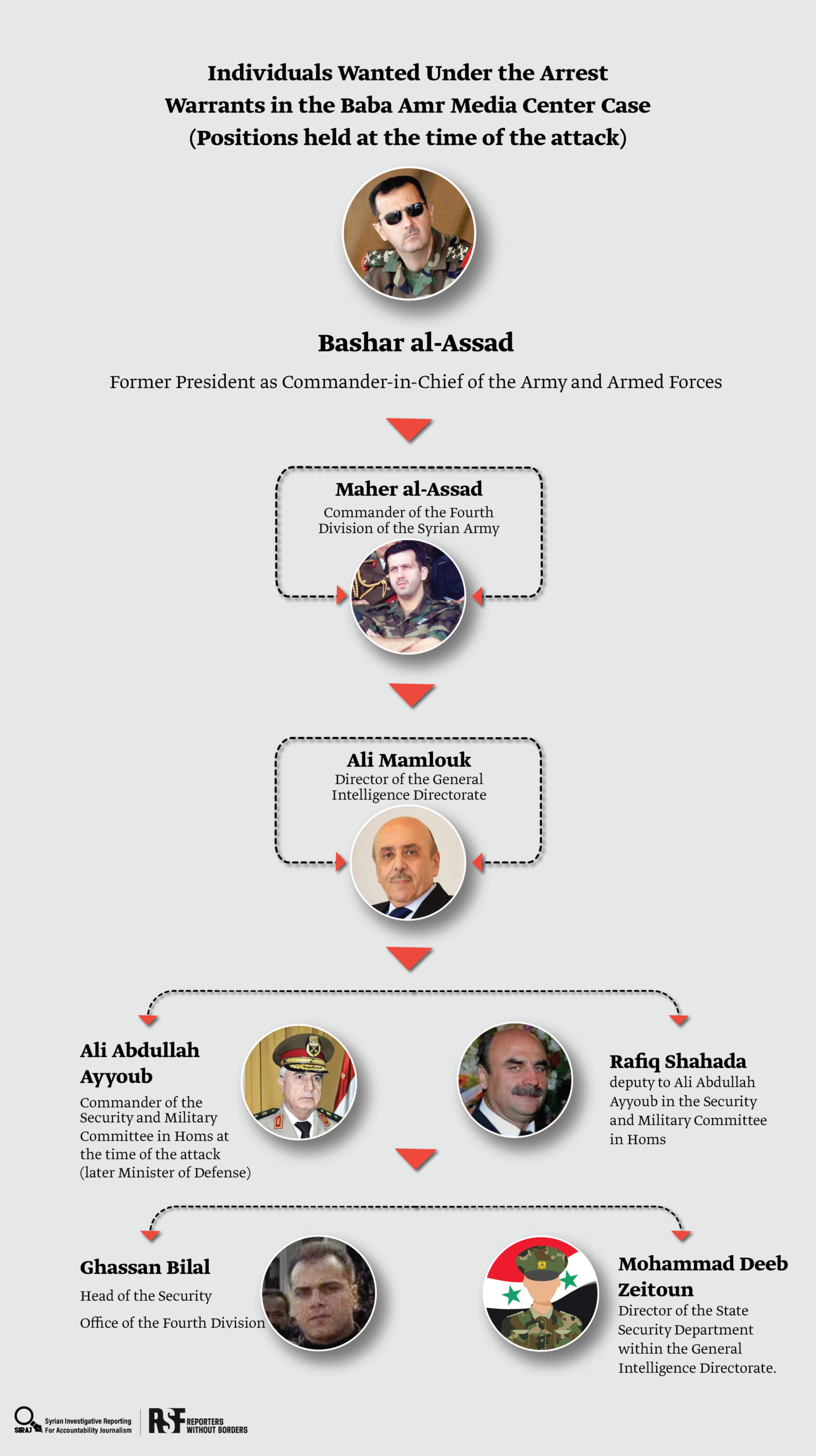

On September 1, 2025, the French judiciary issued an indictment ordering the issuance of seven arrest warrants against senior Syrian officials over the 2012 shelling of the Baba Amr media center. The warrants include former president Bashar al-Assad and several high-ranking officers, accusing them of complicity in war crimes and crimes against humanity related to the February 22 attack.

Shalti stated: “We proved that the targeting of the center was deliberate through three key elements. First, documents we obtained for corroborative purposes indicate that the Syrian regime was aware of the entry of non-Syrian individuals from Lebanon. Security branches were notified of the entry of non-Syrian figures through official cables, meaning the regime was aware of the journalists’ entry at the moment they crossed the border from Lebanon.”

A witness in the case, using the pseudonym “Ulysses”, who worked in the Military Intelligence branch, confirmed that Major General Ali Mamlouk was informed in December 2011 by Lebanese sources on the arrival of the journalists in Syria. Mamlouk, then head of the General Intelligence Directorate, informed all his counterparts in security branches to locate and arrest the journalists.

The second element, according to Shalti, was that once journalists began publishing from the area, their geographical locations became identifiable to the regime.

A defected Syrian officer stated: “The intelligence branch 225 was responsible for monitoring communications, using technical equipment to locate communications made through non-Syrian SIM cards or satellite internet, using devices known as ‘al-Rashedat’,” globally referred to as IMSI catchers.

The third element, Shalti added, involved reconnaissance aircraft and local informants. In this context, he explained that investigators identified several informants through consistent testimonies from defected officers and witnesses in Baba Amr.

In an interview with the RSF and SIRAJ joint-investigation team, French journalist Édith Bouvier said: “The drones were really awful. We were listening to the sound of it all day, so we knew that they were continuing to track us, to try and find us.”

According to Ulysses, on the night before the attack, February 21, 2012, a female informant was brought to the Homs military academy to meet with more than 10 senior intelligence and army officers. In this meeting, she confirmed the exact location of the media center, and the entire operation was prepared.

Shalti concluded: “When these elements are combined, it becomes clear that the Syrian regime had full knowledge of the journalists’ location, their presence, and their movements within the neighborhood.”

The Soviet 130-millimeter artillery gun

On the day of the attack, February 22, 2012, a soldier within the Syrian army uploaded a video on YouTube showing a shelling that targeted the Baba Amr neighborhood. The footage displays several artillery guns that experts and defected officers confirmed to be Soviet-made M46 field guns, known among Syrian army officers as the “130 gun,” a reference to the 130-millimeter caliber of the shells it fires.

In the background of the video, the gate and a building for Regiment 64 of the Syrian regime’s army are clearly visible—the same unit that launched the shelling targeting the media center.

By comparing the visual evidence in the video with satellite imagery, and showing both to defected members of Regiment 64, the investigators confirmed that the building visible in the footage is indeed the regiment’s headquarters.

Video published by a Syrian army member showing shelling launched from Regiment 64 on February 22, 2012 -YouTube.

The video also shows the presence of at least six M46 artillery guns, which matches satellite imagery of Regiment 64 from May 2012, that reveal six guns of the same model positioned in firing mode toward the north, in the direction of the Baba Amr neighborhood.

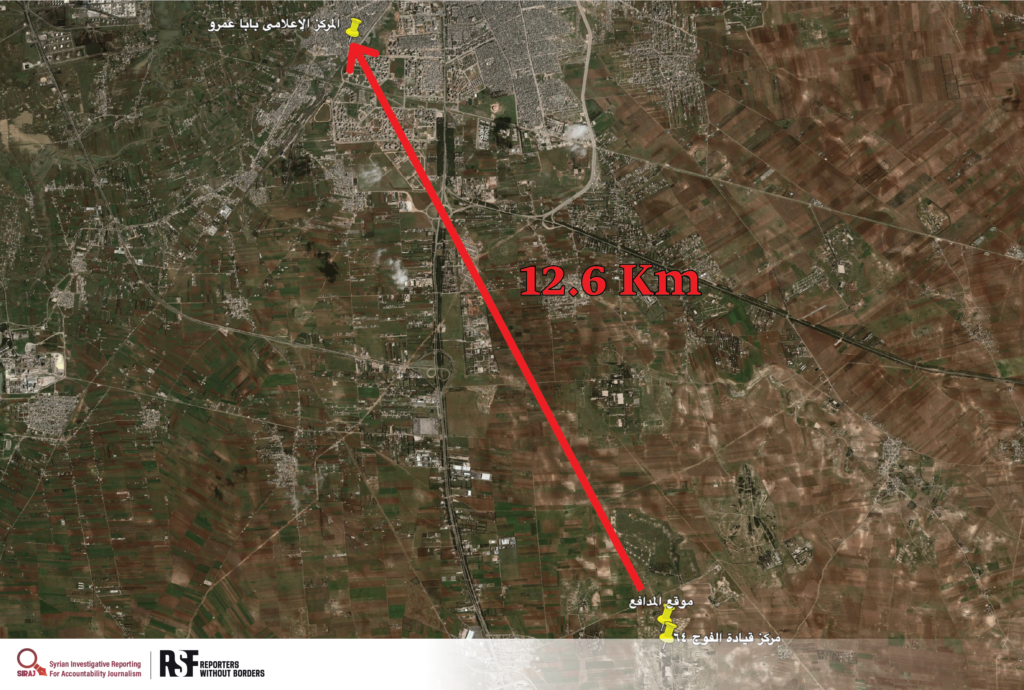

Other videos of the shelling of Baba Amr, reviewed by weapons experts and former military officers, confirmed that the weapon used is a M46 130-millimeter field gun. Based on this, they confirmed that the shelling originated from a single source and, by comparing the sound of launch with the sound of impact, determined that the 130-millimeter shell takes 10.95 seconds to reach the target. Based on the specifications of this gun, the shells were fired from a distance of about 12 kilometres.

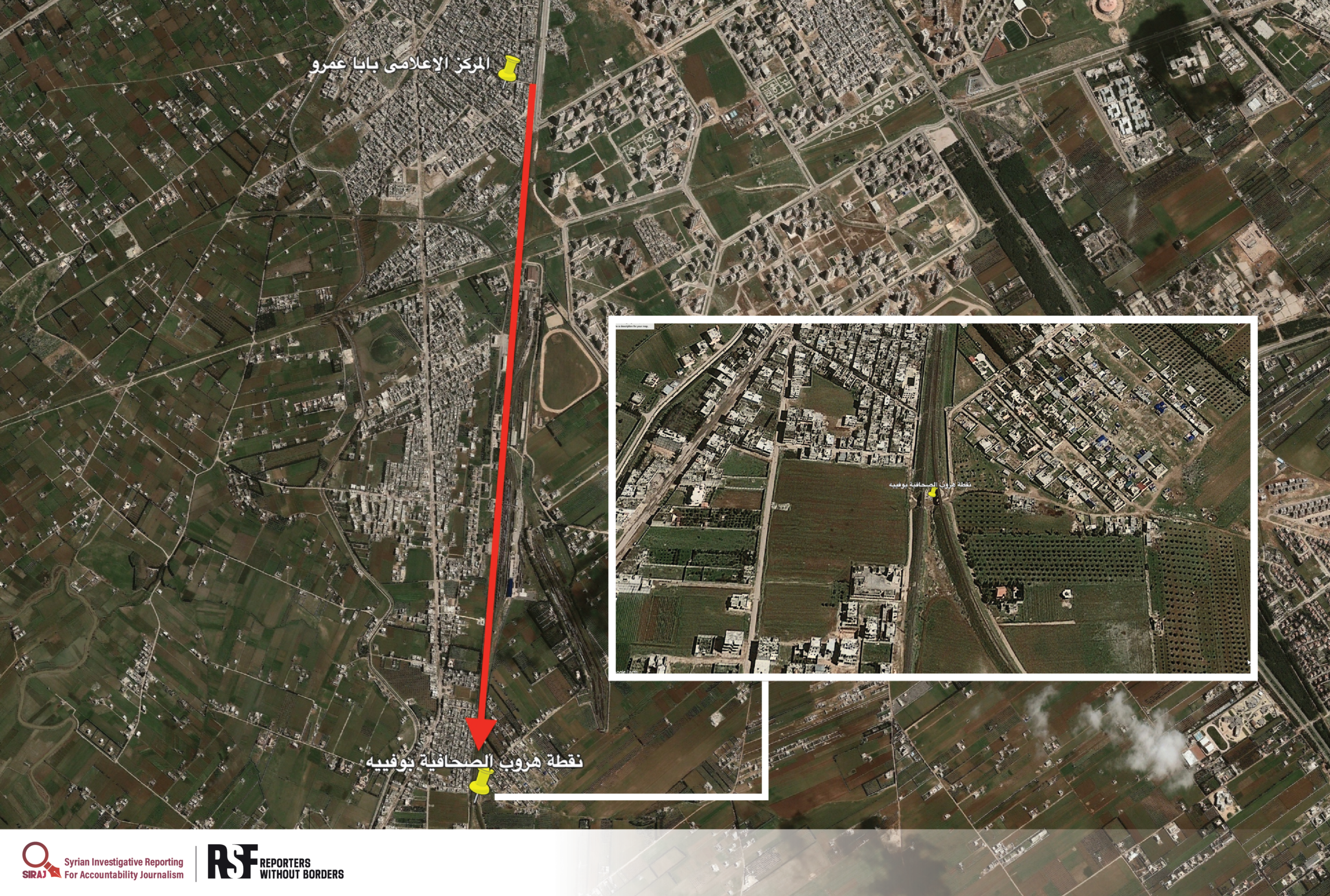

The investigators conducted a geospatial analysis using satellite imagery, outlining a semi-circular search area for artillery positions with similar characteristics within a 12-kilometer radius south of the Baba Amr media center. The only location that matched these criteria, at a distance of 12.6 kilometers, was Regiment 64.

A chain of complicity

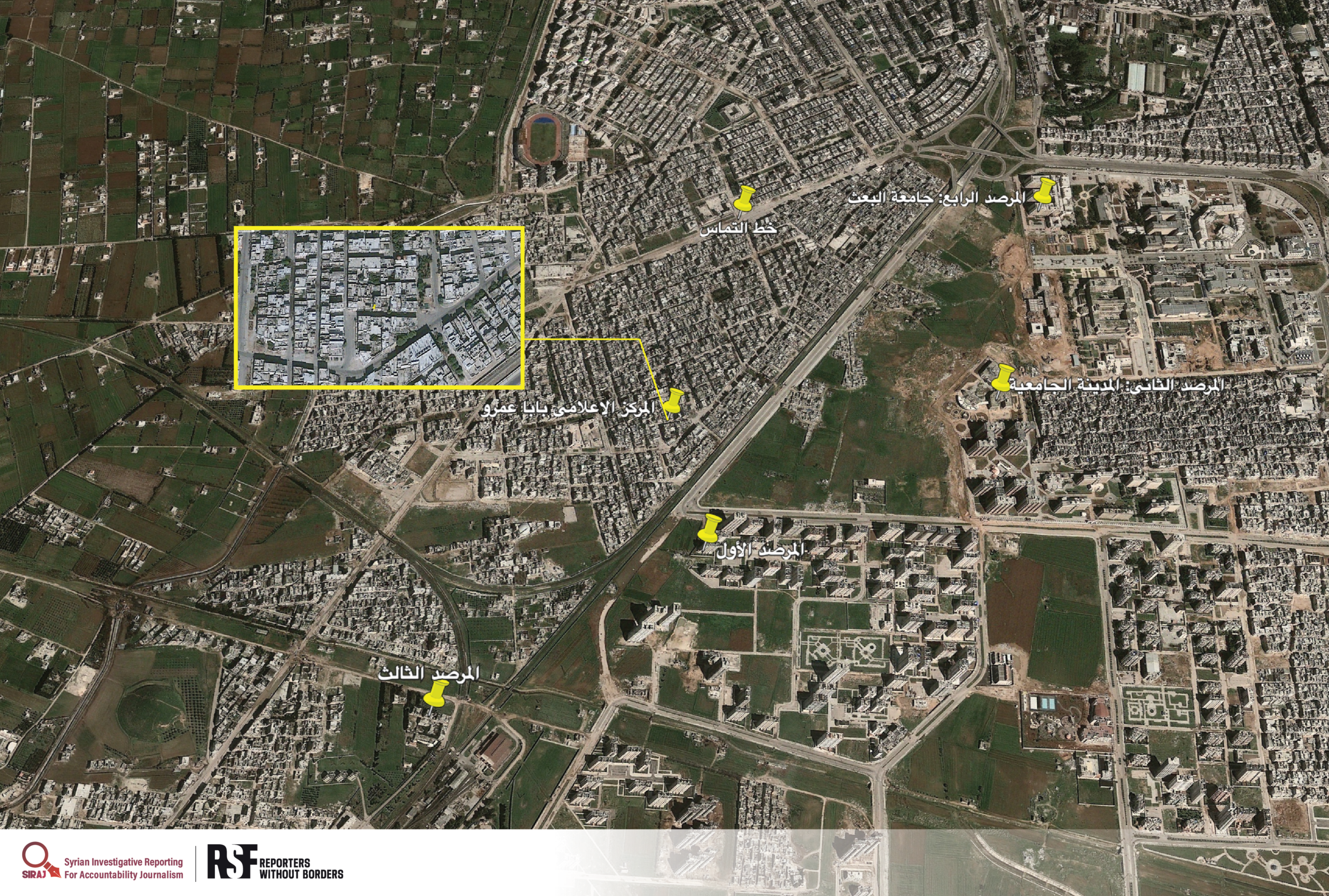

The media center was surrounded by high-rise buildings, including the dormitory and Al-Baath University buildings, as well as residential towers in the Al-Insha’at neighborhood, which were used by regime forces to monitor the area. The media center was also located south of the front line separating regime forces from the Free Syrian Army and other opposition factions, making it subject to prolonged surveillance by regime forces.

At the top of the chain of responsibility for the strike was former regime leader Bashar al-Assad, in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces.

Next in the chain was Major General Ali Abdullah Ayyoub, serving then as the Commander of the Security and Military Committee in Homs. This committee held exclusive authority to issue orders for military attacks and security operations. All military operational orders were issued by Ayyoub, in coordination with his deputy, Rafiq Shahada, who shared responsibility for military decision-making.

After the decision was made, orders to target the media center were sent to Colonel Shaaban Al-Ouja, Commander of Artillery Operations in Homs and head of the Rocket Battalion, to carry out the attack. Al-Ouja then relayed the order to Colonel Akram Al-Melhem, Chief of Staff of Regiment 64 and head of its Operations Branch, to determine the artillery bearing and firing parameters.

The orders were subsequently sent to the commanders of the three observation posts surrounding the media center to identify precise coordinates: Colonel Bilal Hassan, Colonel Issa Al-Ali, and Colonel Kamal Al-Mohammad. The coordinates were then relayed back to Shaaban Al-Ouja.

Violating International Law

In an interview with the SIRAJ team regarding the legal status of the “media center” as a protected object, Yara Badr the head of the Media and Freedoms Program at SCM, stated: “Media centers, including the headquarters of television channels, newspapers, and news agencies, are considered civilian objects and may not be targeted unless they are directly and effectively used to support military operations (such as broadcasting military orders or providing direct intelligence).”

Fadi Al-Abdallah, official spokesperson for the International Criminal Court in The Hague, said: “The protection of journalists falls under the protection of civilians according to international law, the Geneva Conventions, and the resolutions of the UN Security Council and General Assembly. Journalists are covered by the protection granted to civilians during armed conflicts,” adding, “While there is no specific provision dedicated exclusively to journalists in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, they remain fully protected as civilians.”

The Day of the Attack

Colonel Shaaban Al-Ouja assigned the artillery battery command—represented by Colonel Hussein Issa, Commander of Battalion 465—to prepare the strike. He supervised the positioning of artillery guns toward the designated target before opening fire.

The Baba Amr media center was struck by two artillery shells. The first was a hollow (penetrating) shell, intended to breach the building, verify the accuracy of the coordinates and firing angle, and create panic among those inside, forcing them out of their protective positions. After military observers confirmed that the hollow shell had hit the target and exposed those sheltering inside, a second high-explosive shell was fired at the media center.

In an interview with SIRAJ and RSF, journalist Bouvier confirmed that the center was hit twice that morning, between 7 and 8 AM, describing the horror of the final moments of Colvin and Ochlik:

“I was inside the building when they fired the second shot. I think [Colvin and Ochlik] heard the sound of the last shell, and they were killed on their way back to the building, right at the entrance,” she said.

In a video published by a Syrian activist from inside the media center at the moment it was struck by the first hollow shell on 22 February 2012, the flash caused by the first hollow artillery shell can be seen reflected on the glass of a building opposite the media center. This clearly indicates that the artillery strike originated from the south.

Video from inside the media center at the moment it was hit by the first artillery shell, 22 February 2012.

The investigators geolocated the video and confirmed it was taken from inside the Baba Amr media center.

Between the Artillery Battery and the Observation Post

After the first strike, the journalists decided to exit the media center in pairs toward the opposite street.

The first group consisted of a Syrian journalist and a Spanish photographer, who safely crossed to the building across the media center.

The second group was supposed to include Marie Colvin and Rémi Ochlik. However, after the first group crossed, the observation posts noticed that journalists had begun leaving the building and ordered the firing of the second high-explosive shell.

According to testimonies from defected officers, one of the observation posts confirmed that the journalists had been killed and that the shell had hit its target.

Captain Rabee’ Hamza, who was stationed at one of the security checkpoints forming the siege around Baba Amr, told investigators: “At the time of the strike, it was around eight o’clock in the morning. I was sitting with another officer and heard a conversation over the radio between the observation post and the artillery battery.”

The observation post said, “These are the coordinates of the media center. Observe the shot.” And after the first shell, it followed: “The shot is on target.”

There was a pause between the hollow shot and the explosive one. During that interval, Colvin and Ochlik had exited the media center and were about to reach the entrance of the opposite building when the shell struck them, killing them instantly.

The same shell also injured journalist Bouvier and British photographer Paul Conroy, who were near the entrance of the media center, preparing to leave as part of the third group. Syrian translator Wael Al-Omar was also seriously wounded as a result of the strike.

“I was still processing what to do, and I wanted to be useful. I was injured, and I didn’t even know how severe my injury was,” Bouvier said.

According to a testimony of a defected officer, regime forces celebrated after the fatal strike. Ali Abdullah Ayyoub was quoted as saying: “We got rid of those whores.” At the time, the belief was that everyone inside the media center had been killed. However, after appeals emerged from Baba Amr calling for the rescue of Bouvier and Conroy, the regime realized that some individuals had survived.

From Condemnation to “War Crime”

Since 2017, the Syrian Free Lawyers Association has worked to collect evidence related to the crime in Baba Amr, ultimately securing arrest warrants—the first since the targeting of the media center in February 2012.

The association collected and examined a large body of evidence, enabling the competent French judiciary to issue seven arrest warrants against Bashar al-Assad and several high-ranking regime officers, establishing a judicial precedent of particular significance within the framework of universal jurisdiction.

The evidence submitted relied on multiple elements, including testimonies from defected officers and information related to field-level security arrangements. These included measures reportedly taken against security personnel suspected of assisting the injured journalist Édith Bouvier in leaving the besieged area. The evidence also included subsequent detention cases, among them the arrest of Captain Rabee’ Hamza, one of the commanders of the checkpoints forming the security cordon around Baba Amr, who was held for several years in Saydnaya Prison, along with other colleagues of his who died in detention.

These materials were further supported by testimonies from legal experts, witnesses, and survivors, helping to build a comprehensive case file that characterizes the events as a war crime and a crime against humanity, within a framework that meets the requirements of international criminal justice.

The War Crimes Court in Paris issued the arrest warrants under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows national courts to prosecute crimes even when they were committed outside the country’s territory.

This ruling is considered unprecedented, as previous judicial efforts had failed to establish the intent required to classify the attack as a war crime.

On February 1, 2019, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued a default judgment in a lawsuit filed by relatives of Marie Colvin, awarding $302,511,836 in damages against the Syrian Arab Republic. The court held the Syrian government responsible for Colvin’s death.

However, that ruling was purely civil, classifying the crime as an extrajudicial killing and failing to pursue criminal accountability for senior Syrian regime officials, including Bashar al-Assad.

Samer Al-Dayyi, Director of the Syrian Free Lawyers Association, explained: “The American lawsuit was a civil case that ended with financial compensation. By default, this path does not result in criminal accountability, does not aim to determine individual responsibility or dismantle the chain of command, and does not legally allow for the issuance of arrest warrants.”

Al-Dayyi emphasized that the current proceedings before the French court represent a fundamentally different process. “We are dealing with a criminal investigation into war crimes and crimes against humanity, based on evidence that established deliberate intent and premeditation, and linked the targeting to a broader, systematic attack on a known media center housing foreign civilian journalists.”

Since the early days of the Syrian uprising, Al-Dayyi has worked within a legal team documenting human rights violations and coordinating with field journalists to facilitate access for foreign reporters to areas outside regime control.

According to the SCM, “the path is now far more open for pursuing criminal proceedings in the United States as well… The primary move may be the surrender of Bashar al-Assad and the arrest of the other accused for trial in France or Syria.”

Al-Dayyi added: “The case was initiated at the request of the victims’ families and journalist Édith Bouvier in her capacity as a civil party, and the facts were legally characterized as a war crime.”

From a legal standpoint, proving intentional targeting of civilian journalists during an armed conflict meets the criteria of a war crime. When it is further established that such acts form part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against the civilian population, with knowledge of the broader context, the legal classification extends to a crime against humanity.

When the association began work on this case, the facts and information were fragmented and lacked a unified legal framework. The legal team restructured the file, built a coherent chain of criminal responsibility, and strengthened the element of prior knowledge.

The Syrian Free Lawyers Association’s role went beyond documentation or legal advocacy; it was officially recognized as a civil party in the case by the French judiciary, which specializes in war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The Crown Witness

After the strike, the Syrian regime dispatched two ambulances through the Syrian Red Crescent to facilitate the transfer of Édith Bouvier and Paul Conroy to Lebanon. However, both journalists decided not to leave with the ambulances after a Red Crescent worker warned them they might be arrested on the way, or even worse. An emergency surgical procedure was performed on Bouvier at the site, as she confirmed to the investigators.

Later, an attempt was made to evacuate them through one of the tunnels leading out of the Baba Amr neighborhood. However, Bouvier’s evacuation failed because she was being transported on a medical stretcher inside the tunnel, part of which had collapsed due to shelling. Paul Conroy managed to exit successfully.

In December 2011, several months before the targeting of the media center, the Syrian regime began encircling and besieging Baba Amr through what were then known as the “security cordon forces.” These forces were a mix of regular military units not specifically trained for urban assault.

The cordon consisted of dozens of military checkpoints surrounding the neighborhood. Among them was a checkpoint near the village of Al-Naqeera, commanded by Captain Rabee’ Hamza of Regiment 64, along with 13 soldiers armed with light weapons, tasked with controlling access to and from the area.

When efforts to evacuate journalist Bouvier through the tunnels failed, the last resort was to evacuate her through the checkpoint commanded by Captain Hamza.

Hamza did not want to be exposed publicly and agreed to help on the condition that the journalist would not know his name. He coordinated the operation with a local notable.

On the morning of February 26, 2012, Bouvier was ready to leave Baba Amr, and the vehicle transporting her passed the checkpoint Hamza was overseeing at 9:00 A.M.

Hamza recalled: “I saw some of the people I had been coordinating with inside the car, and Édith Bouvier was in the back seat. She was made to wear a headscarf, and her cast was removed so she would appear like an ordinary Syrian woman. They passed beneath the railway line, from where she was transferred to the border town of Al-Qusayr, and then on to Lebanon, under a strict media blackout.”

After Bouvier reached France and news spread that she had escaped from Baba Amr, the regime launched internal investigations to determine how she had been evacuated. One informant was sent to Captain Rabee’ Hamza, posing as a Baba Amr resident and requesting assistance. Hamza did not suspect he was an informant. Over time, as communication continued and trust was established, the informant learned that Hamza, along with First Lieutenant Qusai al-Hussein, was responsible for smuggling Bouvier out. Hamza was then arrested, along with al-Hussein and several fellow officers.

They were all transferred to the Military Security Branch in Homs, where he was interrogated about how he had helped Bouvier escape. He was then transferred to Military Intelligence Branch 293 in the Mezzeh district of Damascus for further interrogation, where Hamza admitted that Bouvier had passed through his checkpoint—though he claimed he did not know she was a journalist.

Following his confession, Hamza and the other officers were transferred to the infamous Sednaya Military Prison. He was sentenced to death at the request of the prosecutor of the Second Field Military Court, on charges of participating in terrorist acts. The sentence was later commuted to ten years in prison following significant mediation efforts, while First Lieutenant Qusai al-Hussein died in Sednaya in December 2014.

Hamza was later transferred in 2016 to a prison known as “Al-Ballouna” in Homs. On September 24, 2019, he was released and later moved to France, where he now resides.

Samer Al-Dayyi, Director of the Syrian Free Lawyers Association, stated: Following all those arrests and his release from prison, Hamza then became the crown witness in the case brought before the War Crimes Court in Paris.”