To eke out a living, Rama accompanies her mother and younger sister to farms near Salqin city, west of Idlib, where each family is hardly paid 1,500 Syrian pounds (less than a dollar) per day.

“We better die from the virus, if it spreads to the camps, than starve to death, since it is particularly difficult to obtain detergents in the camp,” the mother said, weary of the long arduous day on the farm.

With the money she and her daughters earn, she gets to buy as much vegetables and crops as possible. These, she then turns into food storage for winter.

Displaced from the al-Ghab Plain, the family today lives in the al-Safsafe Camp, near Salqin city. As COVID-19 prevailed, Rama’s brothers, like the rest of the camp men, yielded to unemployment after they lost their jobs in construction.

With the significant spread of the virus, the camps’ people had to grapple with major challenges, most importantly their severely affected jobs. Furthermore, they are toiling to make a living, considering their long stay at the camps, lacking job opportunities and humanitarian aid, which before amounted to food shares and a few healthcare services at best, provided by organizations and civil society associations, the camp’s residents said.

It is dangerous and horrifying, a number of despondent displaced persons at the camps in north Syria said, describing their life there.

“We almost have no food. The aid we get every now and then is insufficient. We are not even getting enough water, drinkable or for household uses,” said Hind Malaki (33 years), a woman displaced from Mount Zawiya to rural Idlib with her three-member family. “My husband was a day labourer, and we struggled only to get bread. Our life in the camp has grown worse than ever.”

The larger proportion of the camps’ residents are displaced from areas in Hama, Aleppo and Idlib, fleeing the military operations launched by the regime and Russian forces. They, thus, sought refuge in less hostile areas, which incubate over two million civilians, the Syria Response Coordinators Group (SRCG) said, adding that IDPs live in 1277 camps, 366 of which are informal.

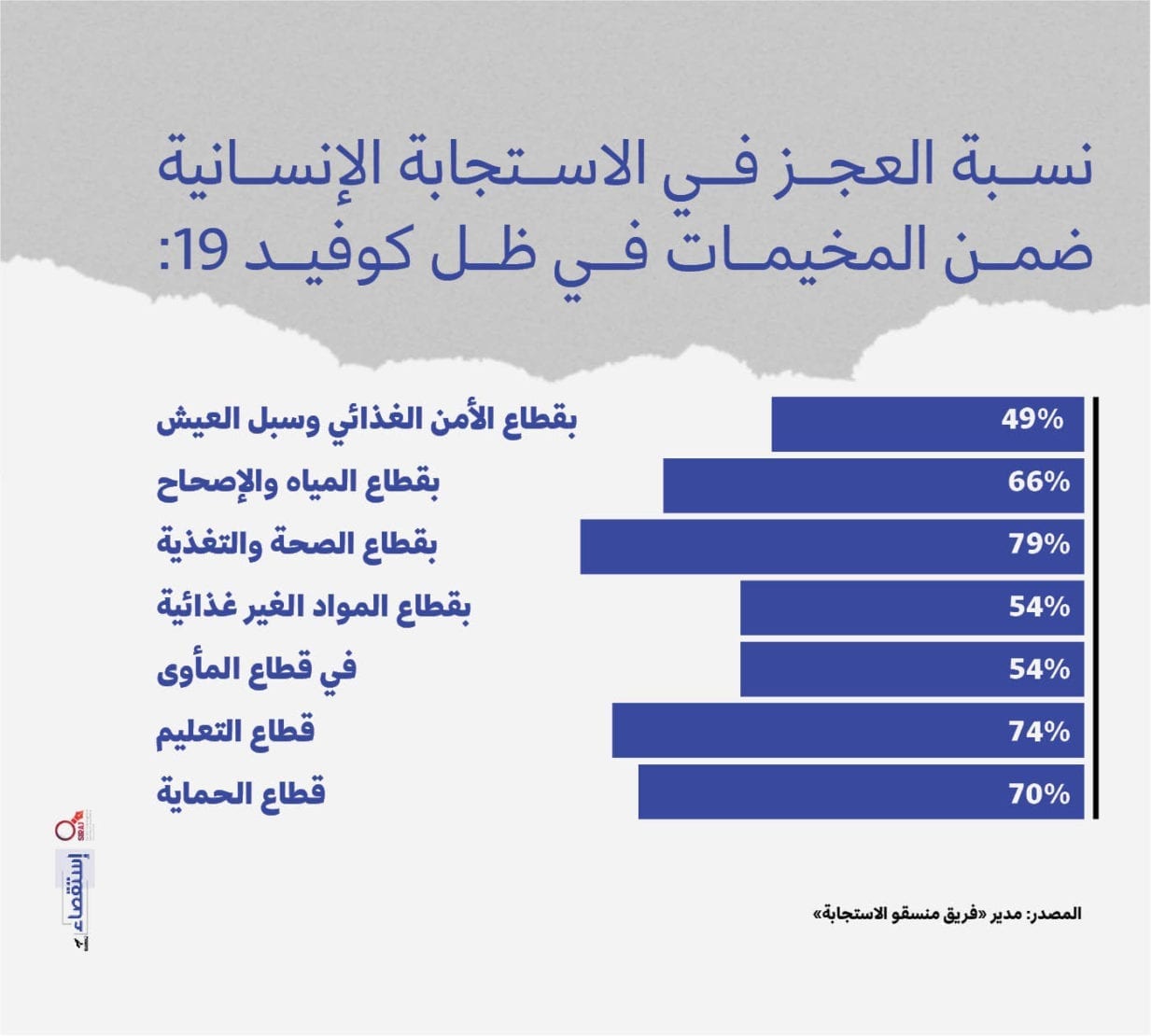

Shortfall in Humanitarian Response within Camps under COVID-19:

Livelihoods and food security sector 49%

Water and sanitation sector 66%

Healthcare and nutrition sector 79%

Non-food items sector 54%

Shelter and housing sector 54%

Education sector 74%

Protection sector 70%

– Source: Director of the Syria Response Coordinators Group

In a statement, the Syrian Civil Defense, a volunteer civil defense organization that helps people affected by the war in Syria, said that the viral outbreak is haunting over four million Syrian IDPs in Idlib province and western rural Aleppo, as well as those in the camps spreading along the Turkish border strip, particularly day labourers, who are stuck in a state of anticipation and are obsessed with the pandemic and infection.

Furthermore, people’s suffering has hit new extremes, for over a million persons live in camps that lack life essentials, according to statistics reported by the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).

“In the camps, people struggle to earn themselves a single day’s living, particularly with the widespread virus, which cost a large proportion of people their source of income,” Dima al-Hak, a member of Idlib Province Municipality, said.

Even though a COVID-19 outbreak in the Syrian displacement camps in rural Idlib and Aleppo will be a disaster, to apply social distancing inside the tents is out of question. However, many people are not scared of the pandemic, as much as they are concerned for their lives and safety.

As the Syrian pound’s value crashed before the dollar, reaching an exchange rate of about 2500 Syrian pounds per dollar in July 2020, according to one currency conversion website, most of the markets were closed down, while prices spiked. Consequently, complaints increased among workers in camps and north Syria, who are tormented by economic and living crises alike.

“My two daughters and I are coerced to work in the fields, getting 500 Syrian pounds each. We are trying to earn our bread money, after my husband and son lost their jobs at the olive factories due to the COVID-19 spread, which devastated our lives to the roots. Both my husband and son had jobs, and our finances were acceptable. However, after they stopped working, we had to work for a low wage that does not exceed 500 Syrian pounds. If the virus continues hitting us hard, we might even consent to work in return for 100 Syrian pounds a day,” Rama’s mother said, who is forty-something.

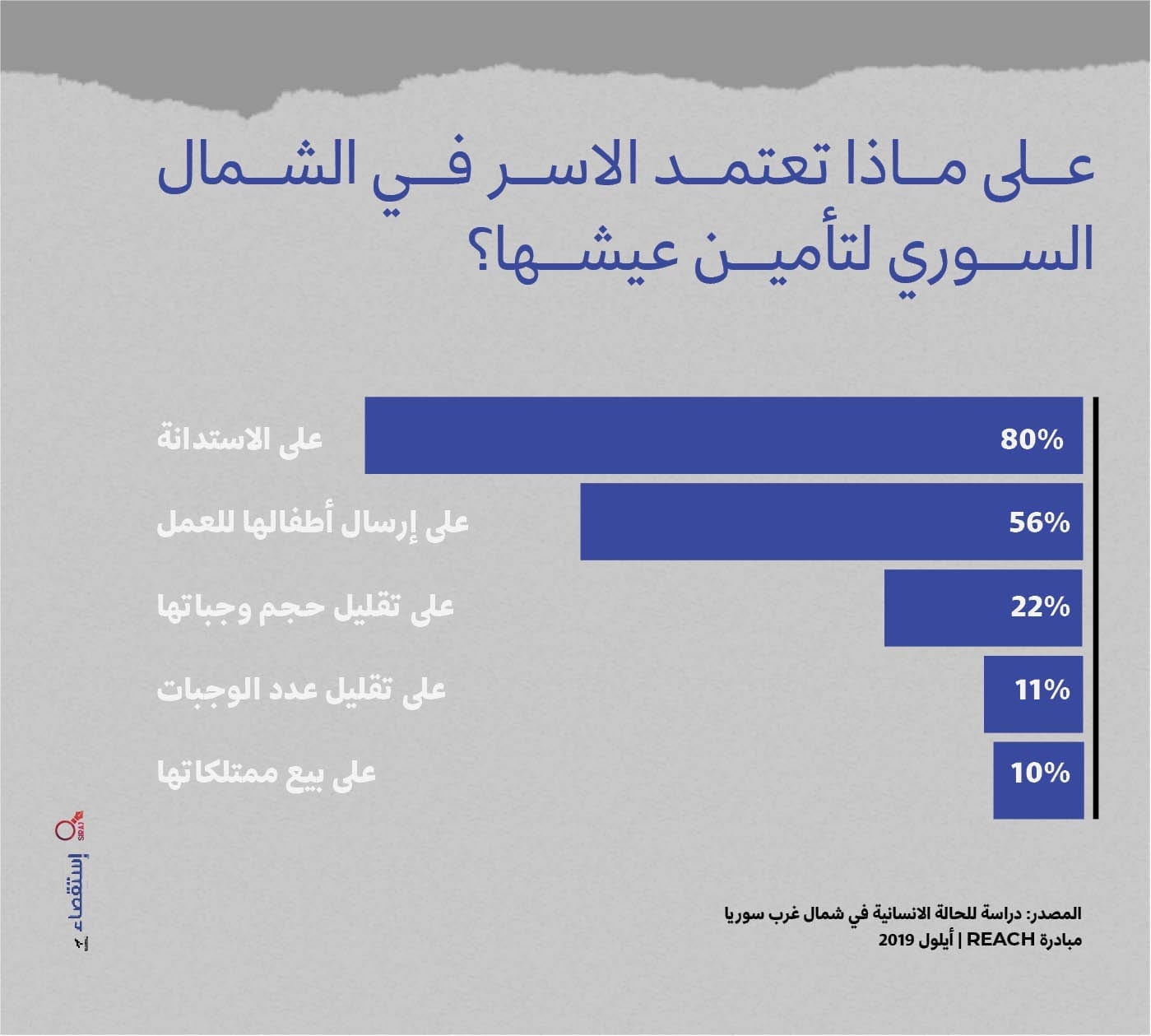

On the same regard, a Humanitarian Situation Overview in northwest Syria, conducted by REACH Initiative in September 2019, scanning 1051 local communities, villages and towns in north Syria, stated that the majority of the Syrian families’ monthly income amounts to a staggering 50,000 Syrian pounds (about 25 dollars), while the income of 941 of the target communities does not suffice to cover the family’s food-related needs.

To make do, the overview further reported, 80% of the families borrow money, 56% send their children to work, 22% reduce the size of meals, 11% skip meals, and 10% offer their household assets for sale.

Yousef Osman, a Syrian young man and a day labourer who sells vegetables in the city of Idlib, shares the demands of other workers: “We need some entities’ support to help us through these wretched conditions, caused by the spread of the virus and death.”

A report, published by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) on 13 July, stated that the COVID-19 impact was added to the repercussions of repeated displacement, persistent security threats, and instability due to local currency depreciation. These concerns boosted the burdens of the area’s population, amounting to 4.1 million persons, 2.8 of whom primarily depend on relief aid to live.

The listed factors, the report claimed, induced a rise in the food parcel’s cost by 68% over a single month, thus threatening to push the rest of the area’s population below the poverty line, who would not be capable of affording their needs unaided.

Concerns and challenges

Muhammad Da’boul (12 years) lives with his family in an informal camp in Atme, rural Idlib in north Syria. The family is extremely concerned over the precautionary measures adopted by the local authorities in Idlib province.

As a wage earner, Muhammad used to make a daily 1000 Syrian pounds, with which his five-member family managed to get along. “I would shuck corn husks every day, boil them and then sell them in the camp. However, with the COVID-19 outbreak, people are no longer willing to buy. My customers went missing, for people are afraid of contracting the virus from vendors,” Muhammad said, his face overcome by confusion.

An estimated 83% of Syrians are below the poverty line, according to the United Nations (UN) 2019 annual report, which assesses major humanitarian needs in Syria.

Muhammad is one among thousands of Syrians who are now in desperate need of assistance amidst the rising prices of commodities in the market and the spiralling COVID-19 crisis.

Local councils in Idlib, responding to the first positive COVID-19 case announced on 9 July 2020, made several statements, providing for banning weekly bazaars in al-Dana, Binish, al-Fu’a and Atme areas “until further notice”, seeking to prevent civilians from gathering. Nevertheless, the area, where three-quarters of the population are on relief aid, is now facing a reality no less threatening than the virus itself.

Major Sources of Income in North Syria

Borrow money from family/friends 80%

Reduce meal size 56%

Children sent to work 22%

Skip meals 11%

Sell household assets 10%

– Source: Humanitarian Situation Overview in Northwest Syria

– REACH Initiative / September 2019

Day labourers left to their own devices

Five months ago, Fatima Muhammad spent long hours behind a sewing machine in her tent in rural Idlib. That was her job for about three years, which she said made her the most happy.

Sewing was Fatima’s source of income, but she is devoid of all resources today, as she cannot continue working. “I am a tailor. I made a living for the family; we asked no one for help. However, due to COVID-19, less customers are showing up. I am no longer capable of affording my needs or sewing tools and materials, such as needles and threads. I am also a heart and hypertension patient. The doctors have cautioned me against seeking another job,” Fatima said.

Relating to sources of income, the Humanitarian Situation Overview in northwest Syria indicated that 85% of the people do not have stable jobs, depending thus on day labour, 84% work on the farms they own, 60% work in business and trade, 14% depend on remittances from outside Syria, and only 13% count on stable salaried labour.

“In the camps, displaced workers, whose main source of income is day labour, are facing a living catastrophe today. Those, however, who work in workshops might be severely affected in two months, if the crisis inflates further,” lawyer Youssef Qadour said, who works with a local team to document violations against the rights of workers in north Syria.

For her part, Dr. Dulama, SRCG director in northwest Syria, listed the key professions in the camps in north Syria: “The majority of the people are day labourers. Others, however, are either tailors or barbers, or work in sell-buy businesses.”

Reporting on the purchase power index in Syria, Numbeo stated that it hit extremely low, scoring only 9.30 points out of a hundred.

Further, the investigative unit interviewed a number of displaced day labourers, who lost their jobs due to the COVID-19 outbreak. They addressed the measures adopted in response and the ensuing repercussions, which aggravated unemployment and poverty rates among IDPs, who were already enduring dire humanitarian conditions before the outbreak and its consequences, which had a catastrophic negative impact on the camps, particularly.

Residents of IDP camps in north Syria face challenging living conditions, in the absence of minimum resources and services, including water, electricity, sanitation and housing, according to the SRCG.

Eight families in the camps, selected randomly by the investigative unit, reported that despite losing their jobs, no organizations came forward to help day labourers, covering neither of their needs, especially ones related to relief and healthcare.

In the camps, key professions are farming, sewing, vending, building, shop keeping, transporting people, hairdressing or selling commodities on stalls.

Dreading haunger

Under the COVID-19 crisis, the IDPs challenging condition effected a great shortfall in the humanitarian response within the camps, which amounted to 49% in livelihoods and food security sector, 66% in water and sanitation sector, 79% in healthcare and nutrition sector, 54% in non-food items sector, 54% in shelter and housing sector (providing tents to informal camps), 74% in education sector, and 70% in the protection sector, the SRCG reported.

Over 5000 persons live in the al-Safsafe Camp in rural Idlib, north Syria, most of whom sought the camp in batches coming from al-Ghab Plain in 2013. They know no other profession but farming, given the nature of the area they fled.

“Before the COVID-19 outbreak, over 40% of the camp’s residents had day jobs at olive and canned food factories. Their daily wages, however, did not exceed a 1000 Syrian pounds, which was acceptable and sufficient to support the family, for all the members worked in these factors. As the virus started spreading, the factories were shut down, boosting unemployment and poverty rates in the camp, which already lacked healthcare and food aid,” the camp manager Wael al-Jasim said, describing the suffering endured by the day labourers.

Mostly covered in blue tarpaulin, several informal camps rest between fields and hills, such as those in western rural Idlib, near the Syria-Turkey border in Jisr al-Shughur area.

Set up in 2014, these camps shelter families that fled from rural Latakia and western rural Idlib. They all live in low-quality dwellings that turn into swamps in winter, while unbearable during the scorching summer.

“We live in this tent, the eight of us,” Ahmad al-Barhou said, a thirty-something man, who lives with his family, while also taking care of his sister and her children.

He pauses, and then adds: “My sister lost her husband during a Syrian regime air raid on our town in the Turkmen Mountain, rural Latakia. I made a living for my family, my sister and her children. I had a modest vegetables stall. My work stopped due to the coronavirus outbreak and the people’s inability to purchase as the Syrian pound crashed.”

Addressing purchase power, several financial overviews indicated that the living costs of a five-member-family is 300,000 Syrian pounds, or 200 to 250 dollars. Nevertheless, these figures are eight to 10 times less than the actual costs.

Delivery

Before the outbreak, the camps’ people suffered from long-term unemployment, lacking money and job opportunities. But still, many of them are trying to forge themselves a chance and make a living to improve their life.

To earn his living, Ghadeer al-Hamwi (29 years) transported passengers and delivered commodities aboard his motorcycle in the Atme Camp on the Syria-Turkey border. However, there are no errands to run these days.

Standing next to his motorcycle, Ghadeer said: “I transported customers between the camps and to marketplaces for a bit of money, aboard my motorcycle that consumes little oil. The transportation fee is also less compared to cars. So, I had many customers before COVID-19. With the restrictions, preventative measures, and the distancing rules, as well as the rising concerns which accompanied the virus, the people stopped seeking my services. I ended up jobless.”

On 28 July, the Idlib Healthcare Directorate reported new cases, which brings the total case number to 29 in the area.

The new confirmed case is in Idlib city, the directorate stated, while larger case numbers are in the two cities of Sarmada and Sarmin in rural Idlib, as well as near the camps in Azaz city, rural Aleppo.

“Inside Syria, over 11 million people need humanitarian assistance, of whom over four millions are children,” Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, said in early March.

In north Syria, Ghadeer and fellow day labourers wait for the COVID-19 crisis to end, to resume their jobs after a two-month interruption.

Ghadeer, who by now sat on the ground near his motorcycle inside the camp, stressed that the condition of his family, consisting of four children, is tragic, while he is unable to meet their needs, or even make a living. “Work has stopped. Unfortunately, we are offered no assistance or food aid. A disaster is looming, a lot more dangerous than the virus. It is starvation,” he said.

The Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ)