Syrian government blocked UN earthquake response in opposition areas. An investigation by Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (Siraj) and MEE has also prompted accusations of negligence against UN officials who, critics say, failed to make use of protocols and principles that should have allowed them to send in rescue teams on humanitarian grounds even without the government’s consent.

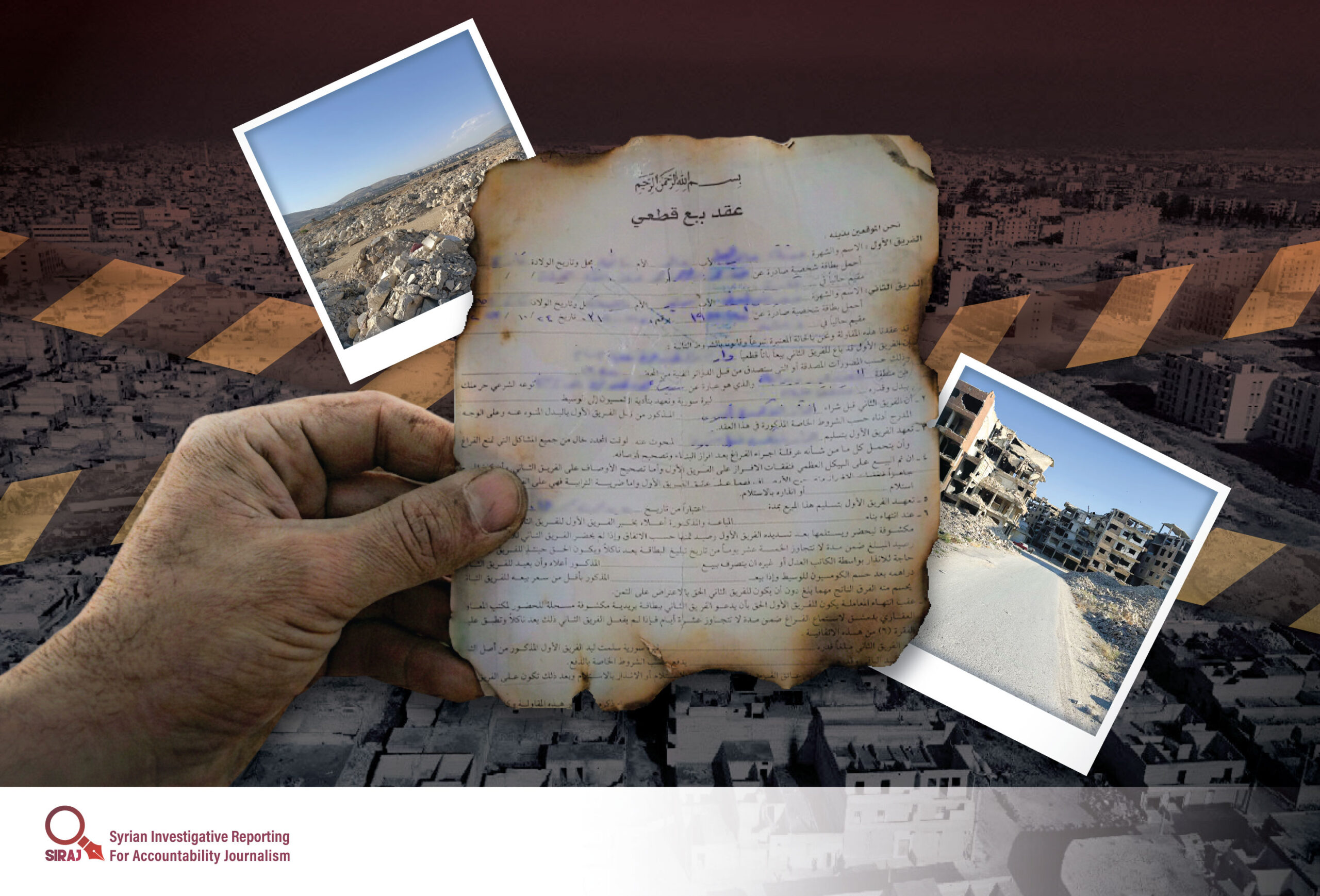

The 6 February earthquake caused widespread destruction over a large area of southern Turkey and northwestern Syria.

Within Syria, the worst-hit region was the opposition-held enclave, including Idlib and parts of Aleppo province, where at least 4,191 people were killed, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).

In government-controlled areas, the death toll was at least 394 people, with most of those deaths reported in the town of Jableh in Latakia province, according to SNHR.

Other sources put the death toll in Syria even higher. A UN spokesperson told Siraj that at least 6,000 people had died in the country. The International Medical Corps said in April that 7,259 people were confirmed killed in Syria.

After more than a decade of war, the opposition-held region was already in a state of humanitarian crisis, with a population of 4.6 million swollen by those displaced from other areas by the conflict and aid deliveries into the enclave long restricted to a single border crossing from Turkey.

Search and rescue efforts after the earthquake largely relied on volunteers from the Syria Civil Defence, the so-called White Helmets who for years have operated as a de facto emergency service in opposition-held areas pummelled by air strikes and shelling.

Footage showed White Helmets volunteers and others desperately searching for survivors by digging through rubble with their hands and basic tools, highlighting the lack of specialist equipment and the improvised nature of the rescue effort.

“After the earthquake, I evacuated my three daughters from the house to the car and didn’t see them for five days,” said Ahmad Yaziji, a member of the Idlib branch of the Syria Civil Defence.

“Several other volunteers left the evacuation areas in order to bury their loved ones before rapidly returning to the rescue. There were so many locations where people were still alive and trapped under the rubble.”

According to the Syria Civil Defence, its volunteers rescued 2,950 people from the rubble and retrieved the bodies of 2,172 people from 182 sites.

The lack of an immediate UN-coordinated response prompted angry criticism from Raed al-Saleh, the head of the Syria Civil Defence.

Saleh told Siraj his organisation had sent distress calls to the UN on the day of the earthquake requesting the deployment of specialist rescue teams.

Opposition authorities including the Salvation Government, the civil administration in Idlib backed by the dominant Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) militant group, and the Turkish-backed Syrian Interim Government in Azaz also requested international assistance.

“Let me be clear: The White Helmets received no support from the United Nations during the most critical moments of the rescue operations,” Saleh wrote in an opinion piece for CNN one week after the earthquake.

“The UN’s failure to respond quickly to this catastrophe is shameful. When I asked the UN why help had failed to arrive in time, the answer I received was bureaucracy. In the face of one of the deadliest catastrophes to strike the world in years, it seems the UN’s hands were tied by red tape.”

The critical importance of a quick response after an earthquake is embedded in search and rescue best practice.

In Turkey there were more than 7,800 live rescues within 24 hours of the earthquake. Despite a massive international effort, only 260 people were rescued alive over the next eight days.

In opposition-held Syria, the situation was very different. Families of some of the victims interviewed by Siraj have described hearing voices trapped under collapsed buildings for several days.

They believe their loved ones and many more lives could have been saved if rescue teams with appropriate equipment had been quickly deployed.

Muhammad al-Mustafa, 32, from the town of Jindires near the Turkish border, said he had to listen helplessly to the cries of his two-year-old son Wafeek and other members of his family trapped under the ruins of their home.

“It was like doomsday,” said Mustafa. “I remember how the voices started to fade on the second day. We couldn’t get them out on our own. There was so much rubble we needed specialist equipment.”

A search team eventually retrieved the bodies of Mustafa’s wife, son, parents and three siblings.

“The fact I could hear my child pleading for me to save him while I was unable to do so devastated me the most,” said Mustafa.

Similarly tragic scenes were playing out in towns and villages across the northwest.

In Bseenah, near Salqin in northwest Idlib province, 39-year-old Rami al-Abdullah said he could hear the screams of his wife and eldest daughter trapped under the rubble for two days after the quake. Only his one-and-a-half-year-old son was eventually pulled out alive.

“The whole village was demolished, and the Civil Defence could not reach everyone and save them,” said Abdullah. “Residents were trying to help, but they were afraid of aftershocks and new collapses.”

‘Coordination mechanisms’

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Ocha) operates an international emergency response system with the capacity to send rescue teams anywhere in the world within hours of a disaster.

The two main organisations, described by Ocha as “coordination mechanisms”, within this system are United Nations Disaster and Coordination (Undac) and the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (Insarag).

Undac’s responsibilities include assessing and coordinating emergency response missions, while Insarag is a network of search and rescue teams from 90 UN member states and international organisations.

Undac and Insarag typically send teams into disaster zones at the request of a government. But UN guidelines also allow for rescue efforts to be initiated by a UN resident coordinator in the affected country.

According to several sources who spoke to Siraj, including el-Mostafa Benlemlih, the UN’s resident coordinator in Syria until earlier this month, the Syrian government did file a request to the UN for help, but this was limited to government-controlled areas.

Benlemlih, who spoke to Siraj while he was still in the role, described Undac’s work as a “complement to national efforts”.

“The Undac team was deployed as soon as they received a request from the usual channels [the Syrian government]. The team was deployed to assess the situation in Aleppo, Latakia, Tartous, Homs and Hama,” said Benlemlih.

Asked why Undac had not deployed to opposition-held areas, Benlemlih said the UN had been “fully prepared to support those affected in Idlib and [opposition-held areas of] Aleppo”.

But he added: “However, the activation of the response system is linked to the approval of the concerned authorities, and is also linked to the provision of mechanisms to support logistical work and protection. These conditions were not available even for the humanitarian support we tried to deliver in the first hours of the disaster.”

Earlier this month, the UN named Adam Abdelmoula as its new residential coordinator in Syria.

Documents obtained by Siraj also show UN and Syrian officials discussed sending aid convoys – but not search and rescue teams – into opposition-held areas in the days after the earthquake.

But no convoys were sent across the front line. According to Reuters, the delivery of aid from government-held areas was opposed by HTS.

Details about Insarag’s response within Syria, and issues which hindered the UN rescue effort in the country, were discussed at a meeting of Insarag team leaders in Singapore on 28 February.

Search and rescue teams from Russia, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates were deployed to Latakia, and teams from Tunisia, Armenia, Algeria and China were deployed to Aleppo, according to a presentation delivered at the meeting.

But challenges faced by Undac and Insarag included a “lack of awareness of the Government of Syria of the international response mechanisms” and the “lack of a basic structure to receive and coordinate international assistance including USAR [urban search and rescue]”.

Team leaders complained that coordination had been complicated by the involvement of multiple entities, including civil defence, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and national security, and by an “inconsistent approach of LEMA [local emergency management agency] in assigning USAR teams to geographic sectors”.

The Syrian government had not responded at the time of publication to questions from Siraj and MEE about why it had not asked for international rescue teams to be deployed to opposition-controlled areas.

In response to questions about why Undac and Insarag teams were not deployed into opposition-held Syria, Jens Laerke, a spokesperson for Ocha, said the deployment of search and rescue teams through Insarag was a matter for national governments rather than the UN.

Laerke said: “To be clear, the United Nations does not have search-and-rescue capabilities, including heavy machinery, nor does it decide which teams deploy to which countries for how long.”

Ocha’s role through Undac, he said, was limited to coordinating the work of search and rescue teams and sharing updates about casualties, damage and requests for assistance.

“While the UN can decide where to deploy its own staff, the decision to deploy national search-and-rescue teams rests solely with the national governments of those teams,” said Laerke.

‘Speed is critical’

Yet the failure of the UN to coordinate the deployment of search and rescue teams into opposition-controlled areas appears to fall short of Undac’s own guidelines on responding to “complex emergencies”, such as in countries in a state of civil war.

These guidelines are contained in the Undac Handbook, a reference guide for Undac team members involved in emergency missions.

The handbook acknowledges that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states must be fully respected, and that humanitarian assistance should be provided with the consent of the affected country.

But it makes an exception in circumstances in which “the legitimacy and territory of the State is under, often violent, dispute”.

The guidance reads: “This situation makes the adherence to the above principles problematic in complex emergencies. In these cases the commitment to the victims may supersede the commitment to the State.”

The handbook advises that “coordination efforts will need to acknowledge the legitimacy of competing authorities [and]… maintain effective relationships not only with the State but also with the antagonists and political opposition”.

It stresses, too, the urgency of deploying emergency teams as quickly as possible, particularly in the aftermath of an earthquake.

“In a natural disaster speed of response is critical and is measured in hours and days. This is especially so in an earthquake situation where trapped people are unlikely to survive more than 3-4 days unless rescued.”

According to one legal expert, the Syrian government’s failure to request or facilitate the deployment of rescue teams to opposition-held territory may be in breach of principles of international humanitarian law established through the Geneva Conventions guaranteeing access to conflict zones for humanitarian actors.

“If the Syrian authorities refused these teams entry into areas beyond their control, this is an arbitrary rejection prohibited by international law,” said Sama Kiki, executive director of the Syrian Legal Development Programme, a UK-based legal advocacy organisation.

Kiki added that a periodically renewed UN Security Council resolution permitting humanitarian aid to be sent into northwest Syria from Turkey through the Bab al-Hawa crossing offered a further legal avenue, and an established route, for Undac and Insarag teams to be deployed into opposition territory.

Bodies instead of aid

The situation in northwest Syria was in stark contrast to the UN response in southern Turkey, where Insarag deployed 221 search and rescue teams from 82 countries in support of the rescue effort by Turkey’s own disaster agency (Afad), according to documents reviewed by Siraj.

In Idlib, the only international response in the days after the earthquake was a visit by a three-person Spanish team who crossed into Syria through Bab al-Hawa on 9 February independently of the UN aid effort.

Mazen Aloush, the media officer for the crossing, said the visit had been coordinated by a Salvation Government charitable support coordination office. It lasted only a few hours and was limited in its scope to assessing the damage, Aloush said.

Muhammad al-Sadiq, a Salvation Government spokesperson, said the Spanish team had trained local volunteers to use a sensor device to detect people still alive under the rubble.

No other equipment was provided, and hopes of finding any further survivors had by then mostly faded.

The Syria Civil Defence head Saleh told Siraj that assessment teams from a number of UN agencies finally entered opposition-held Syria six days after the earthquake.

“These were needs assessment teams, and not search and rescue,” Saleh said.

“After six days people had already died. No one was left from those who were alive.”

Those critical of the UN’s failure to send search and rescue teams and heavy-duty rescue equipment into Idlib through Bab al-Hawa question remarks, made by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on 9 February, in which he said damage to roads leading to the crossing had hindered the aid effort.

According to Aloush, the spokesperson for Bab al-Hawa, within hours of the earthquake the bodies of Syrians killed in Turkey were being delivered to the border post.

“On the evening of the same day, we received cars carrying bodies from all the stricken Turkish provinces without any problem on the roads,” he said.

Border crossing authorities reported 85 bodies delivered to Bab al-Hawa one day after the earthquake, with the number rising over the next few days to more than 1,200. Photos and videos posted on social media showed some of these bodies being delivered on flatbed trucks.

Laerke, the Ocha spokesperson, told Siraj that cross-border aid into northwest Syria had been briefly suspended due to road damage and because of casualties and injuries among staff at a UN aid hub in Reyhanli.

The failings of the UN response were frankly acknowledged by Martin Griffiths, the UN humanitarian relief chief, during a visit to Bab al-Hawa on 12 February.

“We have so far failed the people in northwest Syria. They rightly feel abandoned. Looking for international help that hasn’t arrived,” Griffiths wrote in a tweet.

“My duty and our obligation is to correct this failure as fast as we can. That’s my focus now.”

The following day, Griffiths was in Damascus for talks with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Soon afterwards, two more border crossings from Turkey into opposition-held northwest Syria had opened for the delivery of humanitarian aid.

Fadel Abdul Ghany, the chairman of the Syrian Network for Human Rights, said that serious questions remained unanswered about the failure of the UN to deploy search and rescue teams into opposition-held territory.

“There was negligence on the part of the United Nations,” he said. “This is incomprehensible, unjustified, immoral and illegal.”

Ghany believes that at least dozens of lives could have been saved if the UN had taken prompt and decisive action. He said he had called on the UN to conduct an internal investigation but had not received a response.

UN officials, he said, had talked at length about the mechanisms and details of the earthquake response, but without providing adequate answers as to what had gone wrong.

“In the end, all of these mechanisms failed,” said Ghany.

SOURCE: Middle East Eye