Online Research Tools and Investigative Techniques

Editor’s Note: The Verification Handbook for Investigative Reporting is a new guide to online search and research techniques to using user-generated content and open source information in investigations. Published by the European Journalism Centre, a GIJN member based in the Netherlands, the manual consists of ten chapters and is available for free download.

We’re pleased to reprint below chapter 3, by Internet research specialist Paul Myers. For a comprehensive look at online research tools, see Myers’ Research & Investigative Links.

Search engines are an intrinsic part of the array of commonly used “open source” research tools. Together with social media, domain name look-ups, and more traditional solutions such as newspapers and telephone directories, effective web searching will help you find vital information to support your investigation.

Many people find that search engines often bring up disappointing results from dubious sources. A few tricks, however, can ensure that you corner the pages you are looking for, from sites you can trust. The same goes for searching social networks and other sources to locate people: A bit of strategy and an understanding of how to extract what you need will improve results.

This chapter focuses on three areas of online investigation:

- Effective web searching.

- Finding people online.

- Identifying domain ownership.

1. Effective web searching

Search engines like Google don’t actually know what web pages are about. They do, however, know the words that are on the pages. So to get a search engine to behave itself, you need to work out which words are on your target pages.

First off, choose your search terms wisely. Each word you add to the search focuses the results by eliminating results that don’t include your chosen keywords.

Some words are on every page you are after. Other words might or might not be on the target page. Try to avoid those subjective keywords, as they can eliminate useful pages from the results.

Use advanced search syntax.

Most search engines have useful so-called hidden features that are essential to helping focus your search and improve results.

Optional keywords

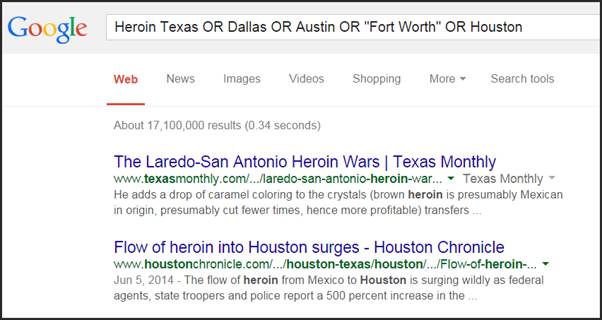

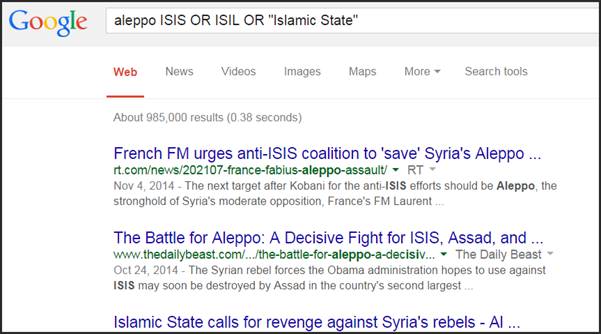

If you don’t have definite keywords, you can still build in other possible keywords without damaging the results. For example, pages discussing heroin use in Texas might not include the word “Texas”; they may just mention the names of different cities. You can build these into your search as optional keywords by separating them with the word OR (in capital letters).

You can use the same technique to search for different spellings of the name of an individual, company or organization.

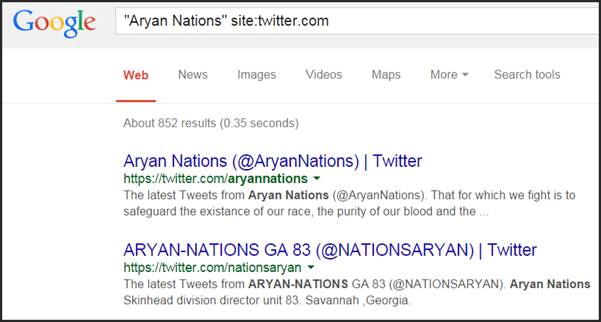

Search by domain

You can focus your search on a particular site by using the search syntax “site:” followed by the domain name.

For example, to restrict your search to results from Twitter:

To add Facebook to the search, simply use “OR” again:

You can use this technique to focus on a particular company’s website, for example. Google will then return results only from that site.

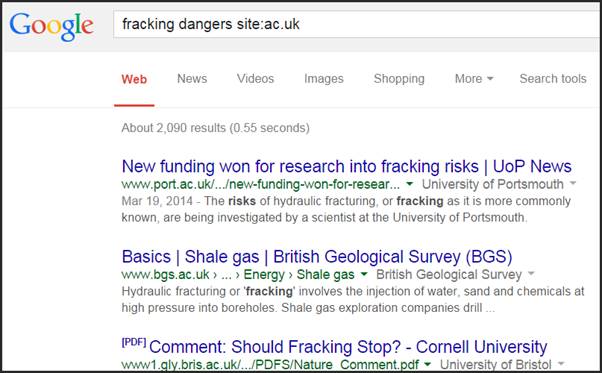

You can also use it to focus your search on municipal and academic sources, too. This is particularly effective when researching countries that use unique domain types for government and university sites.

Note: When searching academic websites, be sure to check whether the page you find is written or maintained by the university, one of its professors or one of the students. As always, the specific source matters.

Searching for file types

Some information comes in certain types of file formats. For instance, statistics, figures and data often appear in Excel spreadsheets. Professionally produced reports can often be found in PDF documents. You can specify a format in your search by using “filetype:” followed by the desired data file extension (xls for spreadsheet, docx for Word documents, etc.).

2. Finding people

Groups can be easy to find online, but it’s often trickier to find an individual person. Start by building a dossier on the person you’re trying to locate or learn more about. This can include the following:

- The person’s name, bearing in mind:

- Different variations (does James call himself “James,” “Jim,” “Jimmy” or “Jamie”?).

- The spelling of foreign names in Roman letters (is Yusef spelled “Yousef” or “Yusuf”?).

- Did the names change when a person married?

- Do you know a middle name or initial?

- The town the person lives in and or was born in.

- The person’s job and company.

- Their friends and family members’ names, as these may appear in friends and follower lists.

- The person’s phone number, which is now searchable in Facebook and may appear on web pages found in Google searches.

- Any of the person’s usernames, as these are often constant across various social networks.

- The person’s email address, as these may be entered into Facebook to reveal linked accounts. If you don’t know an email address, but have an idea of the domain the person uses, sites such as email-format can help you guess it.

- A photograph, as this can help you find the right person, if the name is common.

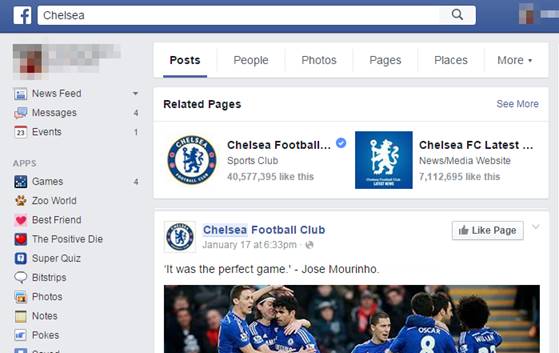

Advanced social media searches: Facebook

Facebook’s newly launched search tool is amazing. Unlike previous Facebook searches, it will let you find people by different criteria including, for the first time, the pages someone has Liked. It also enables you to perform keyword searches on Facebook pages.

This keyword search, the most recent feature, sadly does not incorporate any advanced search filters (yet). It also seems to restrict its search to posts from your social circle, their favorite pages and from some high-profile accounts.

Aside from keywords in posts, the search can be directed at people, pages, photos, events, places, groups and apps. The search results for each are available in clickable tabs.

For example, a simple search for Chelsea will find bring up related pages and posts in the Posts tab:

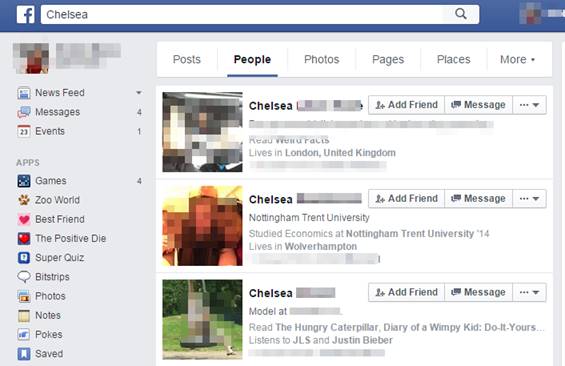

The People tab brings up people named Chelsea. As with the other tabs, the order of results is weighted in favor of connections to your friends and favorite pages.

The Photos tab will bring up photos posted publicly, or posted by friends that are related to the word Chelsea (such as Chelsea Clinton, Chelsea Football Club or your friends on a night out in the Chelsea district of London).

The real investigative value of Facebook’s search becomes apparent when you start focusing a search on what you really want.

For example, if you are investigating links between extremist groups and football, you might want to search for people who like The English Defence League and Chelsea Football Club. To reveal the results, remember to click on the “People” tab.

This search tool is new and Facebook are still ironing out the creases, so you may need a few attempts at wording your search. That said, it is worth your patience.

Facebook also allows you to add all sorts of modifiers and filters to your search. For example, you can specify marital status, sexuality, religion, political views, pages people like, groups they have joined and areas they live or grew up in. You can specify where they studied, what job they do and which company they work for. You can even find the comments that someone has added to uploaded photos. You can find someone by name or find photos someone has been tagged in. You can list people who have participated in events and visited named locations. Moreover, you can combine all these factors into elaborate, imaginative, sophisticated searches and find results you never knew possible. That said, you may find still better results searching the site via search engines like Google (add “site:facebook.com” to the search box).

Advanced social media searches: Twitter

Many of the other social networks allow advanced searches that often go far beyond the simple “keyword on page” search offered by sites such as Google. Twitter’s advanced search, for example, allows you to trace conversations between users and add a date range to your search.

Twitter allows third-party sites to use its data and create their own exciting searches.

Followerwonk, for example, lets you search Twitter bios and compare different users. Topsy has a great archive of tweets, along with other unique functionality.

Advanced social media searches: LinkedIn

LinkedIn will let you search various fields including location, university attended, current company, past company or seniority.

You have to log in to LinkedIn in order to use the advanced search, so remember to check your privacy settings. You wouldn’t want to leave traceable footprints on the profile of someone you are investigating!

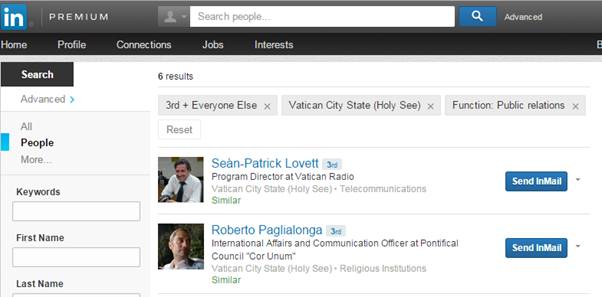

You can get into LinkedIn’s advanced search by clicking on the link next to the search box. Be sure, also, to select “3rd + Everyone Else” under relationship. Otherwise , your search will include your friends and colleagues and their friends.

LinkedIn was primarily designed for business networking. Its advanced search seems to have been designed primarily for recruiters, but it is still very useful for investigators and journalists. Personal data exists in clearly defined subject fields, so it is easy to specify each element of your search.

You can enter normal keywords, first and last names, locations, current and previous employers, universities and other factors. Subscribers to their premium service can specify company size and job role.

LinkedIn will let you search various fields including location, university attended, current company, past company and seniority.

Other options

Sites like Geofeedia and Echosec allow you to find tweets, Facebook posts, YouTube videos, Flickr and Instagram photos that were sent from defined locations. Draw a box over a region or a building and reveal the social media activity. Geosocialfootprint.com will plot a Twitter user’s activity onto a map (all assuming the users have enabled location for their accounts).

Additionally, specialist “people research” tools like Pipl and Spokeo can do a lot of the hard legwork for your investigation by searching for the subject on multiple databases, social networks and even dating websites. Just enter a name, email address or username and let the search do the rest. Another option is to use the multisearch tool from Storyful. It’s a browser plugin for Chrome that enables you to enter a single search term, such as a username, and get results from Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Tumblr and Spokeo. Each site opens in a new browser tab with the relevant results.

Searching by profile pic

People often use the same photo as a profile picture for different social networks. This being the case, a reverse image search on sites like TinEye and Google Images, will help you identify linked accounts.

3. Identifying domain ownership

Many journalists have been fooled by malicious websites. Since it’s easy for anyone to buy an unclaimed .com, .net or .org site, we should not go on face value. A site that looks well produced and has authentic-sounding domain name may still be a political hoax, false company or satirical prank.

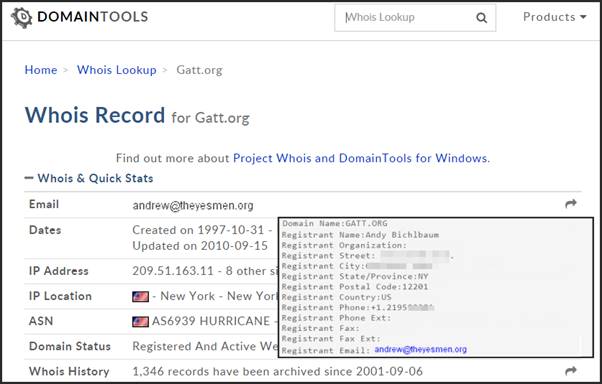

Some degree of quality control can be achieved by examining the domain name itself. Google it and see what other people are saying about the site. A “whois” search is also essential. DomainTools.com is one of many sites that offers the ability to perform a whois search. It will bring up the registration details given by the site owner the domain name was purchased.

For example, the World Trade Organization was preceded by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trades (GATT). There are, apparently, two sites representing the WTO. There’s wto.org (genuine) and gatt.org (a hoax). A mere look at the site hosted at gatt.org should tell most researchers that something is wrong, but journalists have been fooled before.

A whois search dispels any doubt by revealing the domain name registration information. Wto.org is registered to the International Computing Centre of the United Nations. Gatt.org, however, is registered to “Andy Bichlbaum” from the notorious pranksters the Yes Men.

Whois is not a panacea for verification. People can often get away with lying on a domain registration form. Some people will use an anonymizing service like Domains by Proxy, but combining a whois search with other domain name and IP address tools forms a valuable weapon in the battle to provide useful material from authentic sources.

To know more, check out the tipsheets about online research and verification, prepared by Raymond Joseph for the African Investigative Journalism Conference 2016.