Upon arriving in the city of Tobruk in eastern Libya, Ahmed found himself trapped in the hands of a human trafficking network. The 32-year-old Syrian was taken to a warehouse, used as a gathering center for migrants and refugees, one of several in the city.

Located on the Mediterranean coast some 1,300 kilometers east of Tripoli, Tobruk is one of the main transit cities for Syrians and other migrants aiming to reach Europe. Inside the warehouse, Ahmed encountered a “horrifying reality.”

The warehouse had previously been used to store goods and shelter animals, but now served as a makeshift prison. Living in detention in the overcrowded building, Ahmed’s days were a monotonous routine, consumed by fear. There were people of many nationalities, including many Egyptian, Sudanese, Pakistani, and Syrians.

Ahmed is one of the 104 survivors of the terrible boat incident on June 14 when some 650 people drowned near the Greek peninsula of Pylos. Our team interviewed Ahmed twice, first after his rescue and arrival in Kalamos, Greece, and again on July 12.

His testimony, along with those of other survivors, motivated us to trace the journey of Syrian refugees to Libya via countries such as Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. We sought to understand the human trafficking routes and networks, and their connections with military groups controlling Libya

Ahmed, alongside 62 others, had arrived at Benina International Airport in Benghazi by the end of 2022. With the help of Abu Youssef, an Syrian intermediary from Daraa, they had obtained the necessary papers from the Libyan authorities, and plane tickets from Beirut and Damascus for some $1,700 USD per person,

According to the latest report by the Independent fact Finding Mission (FFM) on Libya, the country has hosted over 670,000 migrants from over 41 countries since July 2022, among whom many Syrians.

The FFM described the “wide-scale” exploitation of migrants as a lucrative business, noting that “trafficking, enslavement, forced labor, imprisonment, extortion and smuggling generated significant revenue for individuals, groups and State institutions.”

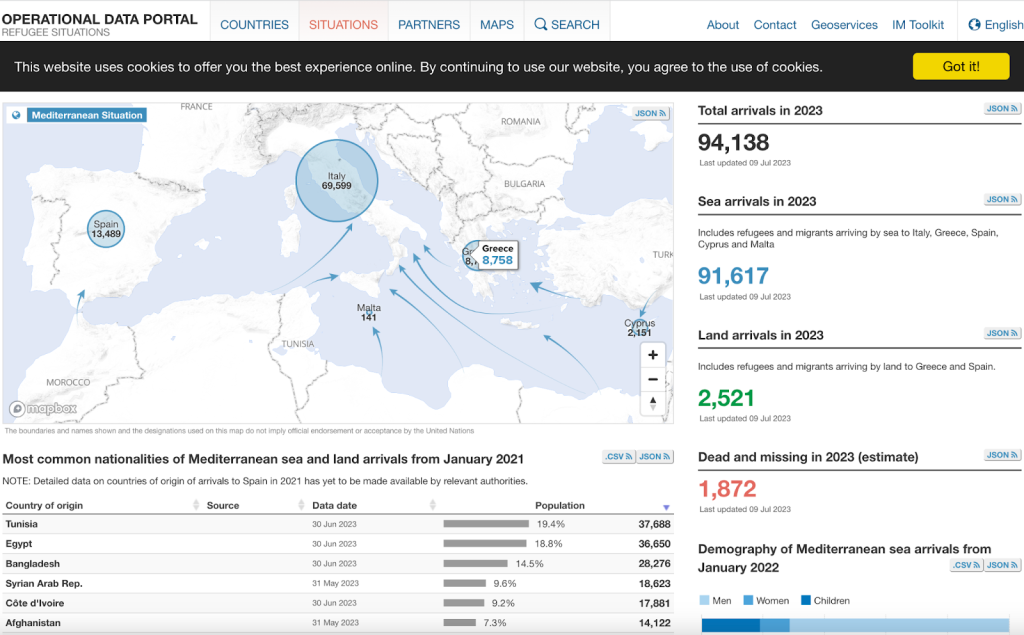

The number of migrants arriving by sea in Europe, particularly Italy, reached 94,138 by June 11, 2023. 1,872 migrants were found dead or went missing. In 2022,159,410 migrants reached Europe by sea, while 2,439 died or went missing.

Blaming the Victim

The Greek maritime court launched a preliminary investigation into the response of the national coast guard. Following the sinking of the boat off the coast of Pylos on June 14, nine Egyptian survivors were arrested on charges of illegal trafficking and involuntary manslaughter.

However, relatives of the detained Egyptians claim they were migrants aboard the ship. Three families provided the investigative team with evidence that their children had paid smugglers for the journey.

The team conducted an interview with one of the smugglers who had arranged the journey for one of the Egyptian survivors accused by the Greek authorities of human trafficking. The team asked him several questions about the journey’s route, timing, and cost.

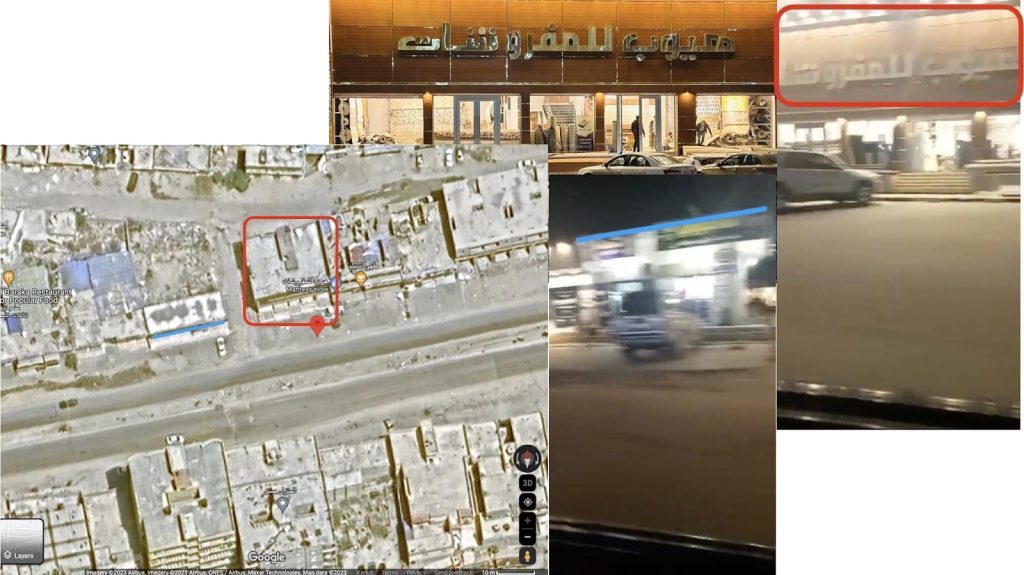

The team managed to trace a video posted on Facebook by the smuggler on June 13, which proved his presence in Libya. He had recorded a street without specifying its location, yet the team found that the video had in fact been filmed on one of the streets of Tobruk.

In response to the team’s questions about the suspects, their detention, and the survivors who had been interrogated regarding the incident, the Greek Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Island Policy stated that it could not give an answer due to the ongoing criminal investigation, which is subject to strict confidentiality, according to the guidelines of the Prosecutor General’s Office at the Supreme Court.

In an email to the investigative team, a European Commission spokesperson said that “the European Commission is not tasked with conducting investigations or definitively proving facts in this case.” As for the governments of Malta and Italy, they did not respond to the team’s queries.

Syrians Traveling to Libya

As part of a group consisting mostly of individuals from Egypt, Syria, and Pakistan, Ahmed spent seven months in detention in a warehouse, awaiting his turn to cross the Mediterranean.

According to Ahmed, the agreed fee for each person’s journey was $4,500, which would be paid to the smuggler. The payment was supposed to be made within a week after reaching Italy.

However, upon arrival to Libya, the migrants were shocked by the awful living conditions. That is when the process of detention and financial exploitation began.

Ahmed described the warehouse as a prison controlled by armed guards, who were often on drugs. The migrants were not allowed to make noise, and they were humiliated in various ways, subjected to verbal abuse and at times physically harmed and even tortured, especially people from Egypt, Sudan and Pakistan. The food was extremely poor, for which the guards would charge exorbitant prices.

Based on information and documents obtained from migrants who traveled through Libya, the investigative team concluded that Syrians enter Libyan territory with security approval. The violence usually starts when they enter Libya.

Libyan human rights organizations, including Solidarity for Human Rights, have documented trafficking, enslavement, forced labor, secret imprisonment, and extortion of migrants.

“The sea ahead …”

For 22-year-old Adel the journey seeking asylum turned into a tragedy. Having left Lebanon after ten years of waiting, Adel’s desire to find a safe route to Europe faced obstacles far beyond obtaining entry visas.

Adel faces several challenges in returning to Syria. He is wanted by the regime and will face arrest if ever he goes back. Lebanon is not a viable option either, since he is no longer welcome as a former refugee.

In Libya, he suffers from a “dire situation,” as he put it. Adel lives on a farm run by a smuggling network with some 50 other Syrian youths. Another farm hosts some 60 Syrian families.

Like all other migrants, Adel is waiting for an opportunity to cross the Mediterranean Sea, because he “no longer cares about anything else.”

“I can’t leave the farm. I feel like we are not humans in Libya, just money that can be seized,” he told Daraj by WhatsApp. “We will cross the sea even if death is our fate. It is better than staying in detention.”

From Asylum to Detention

Most of the warehouses mentioned by the migrants are scattered on the outskirts of the cities of Tobruk and Benghazi. The conditions are poor. Detainees suffer from malnutrition and have no access to clean drinking water. In addition, there is the spreading of contagious skin diseases such as scabies.

Dr. Christoph Hey, a German doctor who spent four months as a medical team coordinator for Doctors Without Borders, said that between September and May in 2022, 22 asylum seekers died, most likely due to tuberculosis.

Each smuggling network controls a set of warehouses where migrants are held before embarking on their sea journey. Each warehouse is equipped with surveillance cameras, while military vehicles and personnel in official attire ensure no one gets close.

According to the testimonies from the people we met, life inside the warehouses was filled with violence, which confirms the 2023 report by the United Nations Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Libya: detainees are regularly subjected to torture and solitary confinement, prevented from communicating with the outside world.

From Broker to Smuggler

Karim left Syria to seek a better life in Europe by the end of 2022. Having worked in Egypt for some time, he decided to travel to Libya. He headed to the city of Benghazi as a potential gateway to Europe.

Karim contacted a Syrian living in Egypt, who arranged an entry visa (security clearance) to Libyai. Karim agreed to pay an advance of $200 and $1,000 upon arrival in Benghazi, which included the cost of a plane ticket. In February last year, Karim left Egypt for Benghazi.

Three survivors of the June 14 boat tragedy described how immigration officials facilitated their travel to Libya upon arrival at the airport. One of them said that someone took their passport upon their arrival and went to the immigration office to get an entry stamp, before escorting them out of the airport.

Karim worked in Benghazi for a month. Here he met another Syrian planning to migrate to Europe via Italy. The latter informed him about a fellow Syrian who had strong connections with smugglers in Libya. He and Karim decided to join the third Syrian man. They paid $4,500 for the journey to Italy.

The Syrian broker worked with a network of smugglers. He had arrived in Libya two years earlier with the intention of reaching Europe. However, when a Libyan man named Mohamed offered him to persuade more Syrians to come to Libya, he decided to stay and work with the smugglers, becoming a part of their network.

Karim and his friend then spent over two months in the Syrian’s house, waiting to embark on the journey with five other people.

Mohamed provided the Syrian man with protection and managed important matters related to smuggling people. Other apartments were filled with migrants, some with as many as 40 people per apartment.

“Mohamed always told us that the journey would be on a very safe boat brought by his cousin in Egypt,” Karim said. “He described the boat as large, accommodating around 300 migrants only. Mohamed was always proud of his cousin who had the same name and worked for the Libyan government.”

Arranging a journey of death

Armed groups in eastern Libya are involved in smuggling migrants as well as intercepting them in European waters. At least two operations were conducted in Maltese waters by a militia known as Tariq ibn Ziyad, which is controlled by Khalifa Haftar’s son.

The operations were conducted in May and July of this year. Four people lost their lives in a boat sinking near the Greek island of Pylos. On a previous trip on May 25, they had been intercepted in international waters, according to their families.

One father said his son had previously been on an intercepted boat and had returned to Malta on May 25. He said that most of the people on the boat, who were forced to return from Malta, decided to take the perilous journey again and boarded the ill-fated boat from Tobruk in June.

The investigation into the sinking of the ship on June 14 showed the involvement of a prominent figure from eastern Libya in the rescue operation in the Mediterranean Sea.

On June 4, before the boat set off on its deadly journey and before migrants were transferred to the departure point on the beach at night, a curfew had been imposed in Tobruk by the Tobruk Security Directorate. Survivors said they were transported with hundreds of passengers to a small bay near Wadi Arzouka before boarding the boat on June 8.

One person’s name has prominently come up in the investigation. Three different sources identified Mohammed A. as being part of the smuggling network. He works in a special forces naval unit known as Frogmen.

One survivor explained that Mohammed A. exploited his position to issue the license allowing the migrant boat to set sail in Libyan waters and ensure that the Libyan coastguards receive money to shut down marine radars. Mohammed A. did not respond to the investigative team’s questions.

Libyan expert Jalil Harchaoui said that human trafficking has flourished in eastern Libya over the past eighteen months. He added that Haftar cannot claim ignorance of the matter, nor can he say that he is not involved.

Libya: A European Obsession

In May of this year, Khalifa Haftar met with Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to discuss migration. In June, the Italian Interior Minister Matteo Piantedosi stated that they would seek cooperation with Haftar to stop the departures of migrant boats.

During that same month, a Maltese delegation met with Haftar in Benghazi to discuss security challenges in the region, especially irregular migration.

According to a Libyan source, the European Union, particularly Italy, has invested in these units since 2020 and carried out rehabilitation work on its ships. According to the European Union, approximately 465 million euros have been provided to Libya since 2015 to combat migration.

Sergio Carrera, a visiting fellow at the Migration Policy Centre (MPC) in Italy as well as a Senior Research Fellow and Head of the Justice and Home Affairs Unit at the Centre for European Policy Studies, calls for human rights to be a fundamental condition for providing funding.

“In case there is evidence of human rights violations during the implementation, those funds should be suspended,” he says.

Today, Ahmed lives in the Mavrovouni camp in the mountainous region surrounding the city of Kalamata. It is the second-largest facility for refugees and migrants in Greece.

“”The days we lived in the warehouses were like hell,” Ahmed said during our interview. “I prefer to drown in the sea five times over than return to those dark places.”

The survivors’ names were changed for security reasons