- A boat carrying migrants left the Libyan coast on June 8 and sank in the early morning of June 14.

- On June 13, the boat was spotted by a European surveillance aircraft that informed the Greek authorities.

- The European Border and Coast Guard Agency offered Greece assistance, but did not receive a response.

- 16 survivors claimed the Greek Coast Guard caused the boat to capsize when trying to tow it into open water.

- The attempt to tow the boat away caused it to capsize and sink

- Survivors statements were manipulated to absolve the Greek Coast Guard of any blame

- Only 104 of the some 750 migrants on board survived. Over 500 went missing and have not been found since.

How It All Began

The morning of June 14 revealed a grim truth when a boat carrying some 750 people sank in international waters off the Greek peninsula of Pylos. The boat had set off from Tobruk in eastern Libya with the aim of reaching Italy.

Only 104 men survived. All other passengers aboard the boat, including many women and children, drowned.

Among the survivors was 27-year-old Syrian Youssef (a pseudonym). In early 2021, Youssef decided to escape Syria and try to travel to Europe through Libya. By the end of that same year, he arrived in Turkey and boarded a plane that took him to Benina International Airport in the Libyan city of Benghazi. Like so many other people fleeing Africa and the Middle East in search of a better life, his ultimate goal was to reach the Italian coast,

Upon arrival at Benghazi airport, his passport was taken from him. He was asked to wait in a courtyard inside the airport. After a short while, a person named Abu Nabal came and called his name. He had Youssef’s passport with him. They got into a car and traveled for two hours until they reached Tobruk.

The city of Tobruk, located 1,300 kilometers east of the Libyan capital Tripoli on the Mediterranean coast, is one of the destinations targeted by Syrians and others aspiring to reach Europe.

To travel through Libya to reach the European coastal countries, particularly Italy or Greece, individuals must communicate with brokers associated with smugglers in Tobruk and surrounding areas. In turn, they meet them upon arrival from the airport and transport them to the waiting camps.

In 2022, 253,205 people attempted to cross the Mediterranean Sea, 42% of whom were intercepted at sea and returned to Libya, despite the country not being a safe place according to Doctors Without Borders. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2022 recorded 3,800 deaths on the migration route from the Middle East and North Africa, the highest death toll since 2017.

The camps in which migrants are held are usually makeshift structures or empty warehouses located in the desert or on the outskirts of towns to avoid drawing attention. Migrants stay there, waiting for the right time to embark on their journey across the sea.

People in the camps are prohibited from communicating with the outside world, as all means of communication, including mobile phones, are confiscated. According to a team of investigators, who interviewed ten individuals who attempted to migrate to Europe through Libya, this restriction is strictly enforced.

“Abu Nabal put me in his car – the car’s windows were tinted, preventing anyone from seeing what was inside,” said Youssef with a trembling voice. “We drove for about two hours until we reached a warehouse. [They] searched us and then took us to the different parts of the warehouse, where I remained detained for three months.”

Visual evidence to determine the cause of the drowning was hard to come by, as the incident occurred in the middle of the sea, and commercial ships and surveillance aircraft were instructed by the Greek authorities to stay away. It was hard to recuperate videos taken by survivors on their phones due to water damage or the loss of their devices.

For this investigation, the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), collaborated with Lighthouse Reports, Der Spiegel, EL PAÍS, Reporters United, and Monitor. Journalists from the same region as many of the passengers investigated the boat’s capsizing and the circumstances of the incident.

Seventeen interviews with survivors were conducted, the most in a single investigation of the incident to date, to compare testimonies. The investigative team also spoke with sources in the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex and the European Commission.

The investigative team obtained crucial legal documents containing two sets of testimonies provided by the same nine survivors. They first spoke to the Greek Coast Guard and then to a local Greek court.

Hour Zero

On June 8, Abu Nabal, a smuggler working in Libya, came to the warehouse and asked Youssef and everyone else to prepare themselves for the journey. They all climbed into an enclosed refrigerated truck with ventilation holes in the roof. After two hours, they arrived at an unknown location and were asked to get out. They walked on a difficult path downhill for about 15 minutes until they reached the shore.

They found themselves by the water, hearing the sound of rushing water and the roar of the waves, Youssef told the investigative team. They saw hundreds of migrants from different nationalities and backgrounds.

They were divided into small groups, put onto small rubber boats, and then transferred to a large boat called The Bulldozer. At dawn, at precisely 5 am, there were some 750 people, including women, children, and elderly on The Bulldozer. Most of them were from Egypt, Syria, and Pakistan.

After three days at sea, a person wearing a mask covering his entire face appeared and shouted: “We are lost at sea.”

According to Ehab, a member of the Consolidated Rescue Group, a group of activists working to assist migrants, the boat was expected to reach its destination within three days. However, circumstances changed, and the boat was redirected to the wrong location, which led to deteriorating conditions on board due to a lack of drinking water. As a result, six people, including a Syrian from Homs and a Pakistani, died of thirst. Some passengers resorted to drinking water from the boat’s engine.

Timeline

On June 13, the overcrowded boat was spotted by a surveillance aircraft belonging to the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex, which informed the Greek authorities.

14:17 CEST: The Alarm Phone, an initiative concerned with rescuing people at sea, received the first call from the boat, during which passengers stated that they were in a difficult situation. The Alarm Phone requested that the boat’s GPS coordinates be shared with them.

15:52: The Alarm Phone received two calls from the boat, but they “were incomprehensible”

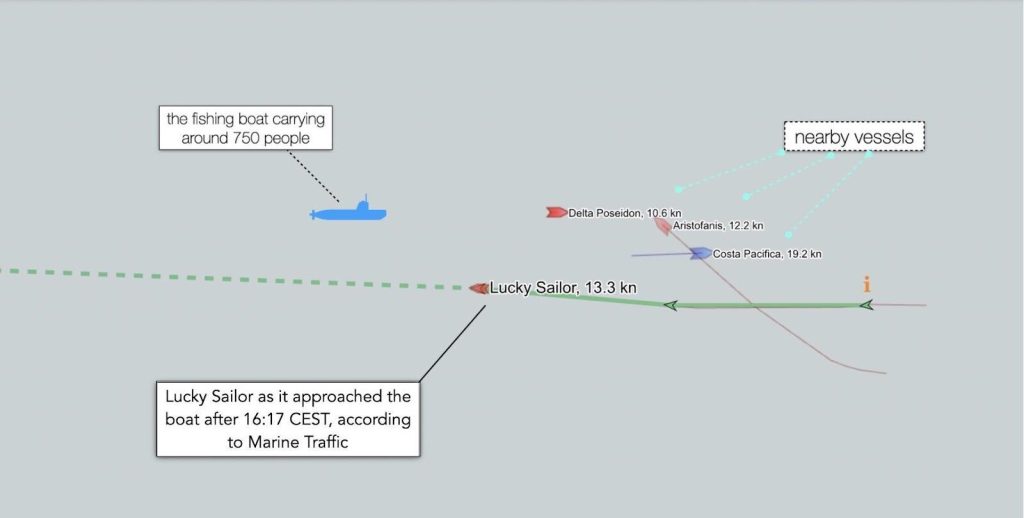

16.17: The Lucky Sailor ship approached the boat

16:53: The Greek Coast Guard was informed that the boat was in distress, as people on board requested assistance. The Greek authorities, Frontex, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Greece, as well as Italy and Malta, had already been alerted.

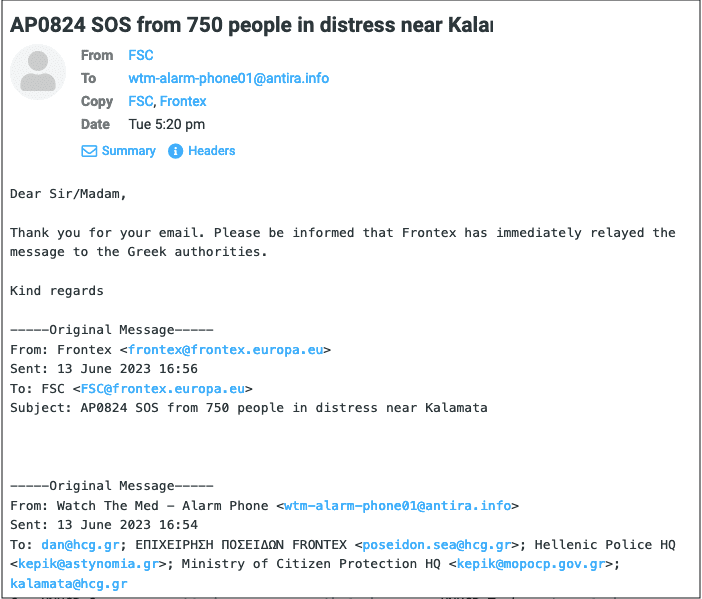

The Alarm Phone initiative sent an email as a distress signal to the Greek and European authorities more than 8 hours before the boat sank.

Frontex responded to the Alarm Phone message, stating that they had informed Greece and shared the information on social media.

- 17:14: Another call from the boat signaled they were in distress, but nothing could be heard.

- 17:20: Another call stated that the captain had left on a small boat, and that people needed food and water.

- 18:00: Contact was made with the commercial ship Lucky Sailor, informing the crew they were near a boat in distress, but they replied that they only follow orders from the Greek Coast Guard.

- 20.00: Another ship, the oil tanker Faithful Warrior, approached the boat around this time

- 22:00: A Greek Coast Guard ship arrived next to the boat.

- 00:46 (June 14): The last communication with the boat took place, but the call was unclear, the words were unintelligible, and the call was disconnected.

- 01:04: According to the captain of the Greek Coast Guard ship, the boat began to sink.

- 01:12: The Greek Coast Guard issued the first distress call to ships in the area to participate in a rescue operation.

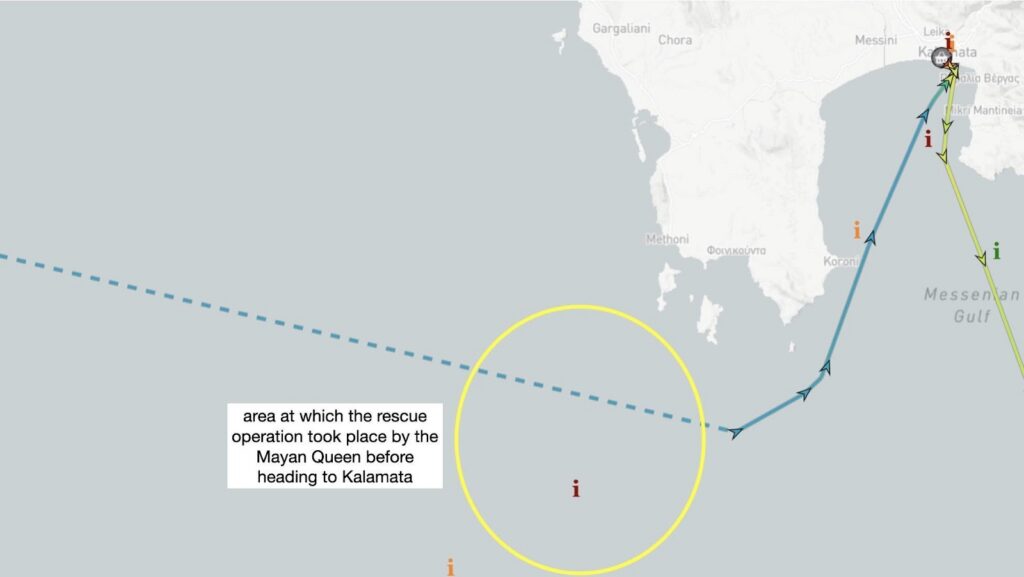

- 01:54: The luxury yacht Mayan Queen arrived to start the rescue operation. In the minutes and hours that followed, several other ships would also arrive.

- 06:37: The luxury yacht Mayan Queen changed its course, as shown by the navigation records on Marine Traffic, after completing a three-hour rescue operation before heading to Kalamata with 100 rescued people on board.

In the early hours of June 14, the boat sank in international waters off the coast of the Greek peninsula of Pylos. Only 104 people survived. From the moment they were spotted by a Frontex surveillance aircraft at 11:49 CET, the migrants on board waited to be rescued for about 13 hours until the boat capsized at 1:05 CET.

According to the survivors’ testimonies, the passengers paid the smugglers fees ranging between $3,500 and $4,500 per person to be transported to Italy. This means the total amount collected from this trip was some $3.37 million, which does not include the costs made by individuals to reach Libya from countries such as Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey.

The Greek Authorities Were Informed

As part of the joint monitoring operation between Frontex and the Italian authorities, known as Themis, a surveillance aircraft successfully located the overcrowded boat within the Greek search and rescue area in international waters on June 13. The aircraft continued to monitor the situation for ten minutes until it had to return to base due to fuel shortage.

According to the available data, the boat was sailing northeast at a speed of six knots per hour. The Greek and Italian authorities were informed immediately, whereby “vital details about the boat’s condition and speed were provided.”

In response to the investigation team’s queries, Frontex confirmed it had offered additional aerial support to the Greek authorities on the same day but did not receive a response from them. The Greek response was limited to requesting assistance in a search and rescue operation off the coast of Crete, where 80 people were in immediate danger.

About four hours later, at 04:05 Coordinated Universal Time (06:05 European time), the unmanned aircraft returned to the boat’s location in Pylos and observed that the Greek authorities were conducting a comprehensive search and rescue operation.

“Unfortunately, there was no trace of the overcrowded fishing boat,” which meant it had sunk.

Ahmed Al-Haqq (a pseudonym), a 26-year-old from Daraa in southern Syria, survived the incident and provided the interviewers with more information about the aircraft he saw in the sky and the conditions they experienced during these moments.

The young man had arrived in Libya from Jordan with his brother and cousin. They were held captive in warehouses by the smugglers, forbidden from contacting the outside world for over three months until the one smuggler asked them to prepare to board the boat heading to Italy, assuring them that their time at sea would not exceed three days.

“After two days of sailing from Tobruk, we got lost at sea as the captain had died,” Ahmed recounted. “Then we asked for help, and an aircraft came, but it didn’t do anything for us. After that, we saw a ship sailing next to us and we asked them for help.”

“A very large oil tanker passed by us with a sign in English saying ‘No Smoking,’” he continued. “They connected our boat to their ship, and we approached them. They threw us some water, and people gathered to drink. But this created chaos on board, and we feared that the boat would capsize, so we moved away from the ship.”

Ahmed indicated that those who tried to save them from drowning were the ones who actually caused them to drown.

“After we moved away from the oil tanker, the Greek Coast Guard came to rescue us,” he said. “They connected our boat to theirs after being next to us. Their boat moved rapidly while towing our unstable boat, which was rocking from side to side, and it capsized quickly after.”

After the boat had capsized, Ahmad came up to the surface. According to him, the coast guards were just idly looking around, making quick circles around them, which created high waves. They remained doing this for 10 minutes.

“We are 104 survivors,” Ahmed concluded. “We know who helped us and who drowned us.”

“The Greek Coast Guard has clear responsibilities and commitments in times of need at sea, which includes coordinating search and rescue operations, getting the help of nearby ships for support, and taking immediate rescue measures when necessary. The coast guard must act quickly and adequately as soon as they know what hardships a ship at sea is facing,” said Nora Marcard, Professor of International Public Law and International Human Rights at the University of Münster.

“If the survivors’ stories on how the coast guards acted are confirmed, for example, their attempts to tow the boat and cause its capsizing, there may be serious legal repercussions,” Marcard added. “They may take the fall for actively endangering the lives of people on board, which is a violation of their duty to protect them according to international human rights conventions and Greek law.”

Drowning in Lies

Sixteen of the seventeen survivors we spoke to confirmed that the Greek coast guard had attached a rope to the boat and attempted to pull it before it capsized. Four of them claimed that the coast guard was trying to tow the boat into Italian waters, while four others said that the coast guard caused more deaths by circling around the boat after it had capsized, creating waves that submerged the boat’s hull.

The survivors affirmed that the coast guard spotted the boat sinking yet only intervened later. The same coast guard summoned nine survivors for questioning less than 24 hours after the rescue operation on June 14.

According to documents reviewed by the investigative team, no accusations were made against the coast guard for its involvement in pulling the boat. Nor is there any evidence of allegations made in the official records of the survivors’ statements.

However, three days later, the same nine survivors met with a police investigator in the city of Kalamata to provide testimonies regarding the incident. It turned out that six of them had changed their statements.

The investigative team obtained the transcripts of the statements provided to both the Greek Coast Guard and the police. Upon reviewing them, it was found that four statements submitted to the Greek Coast Guard showed significant similarities, particularly when the survivors were asked about the cause of the sinking. The answers particularly matched when they were questioned about the reason for capsizing.

Video link to LightHouse

Description: The testimonies of the four survivors as recorded in the Greek coast guard’s records. The highlighted blue indicates the matching parts in their statements.

There are several concerns regarding the credibility of the translations of the survivors’ statements, as one of the three translators is actually an officer in the coast guard. This raises questions about the objectivity and neutrality of the translation.

Furthermore, two of the survivors, whose testimonies showed signs of manipulation, stated that their statements were altered.

We spoke to two of the nine survivors who witnessed the incident, and they informed us that the coast guard deleted parts of their statements regarding the towing of the boat.

“They asked me what happened to the boat and how it capsized,” one of the survivors said. “I told them that the Greek coast guard tied a rope to our boat and pulled us, causing the boat to capsize. They didn’t write that in my statement. When they presented it to me in the end I didn’t find this part.”

He also said that the coast guard pressured him into mentioning certain individuals such as the smugglers being responsible for the operation.

The investigative team received a response from the Greek Ministry of Maritime Affairs regarding the accusations made by the survivors against the coast guard and their alleged involvement in the boat’s capsizing.

The ministry stated that “the requested information is part of the main investigation procedures conducted in absolute secrecy based on instructions from the Prosecutor General of the Supreme Court. As for the details of the Greek Coast Guard’s operational plan, no further comments can be made by our service.”

In its response to the investigative team, the European Commission emphasized the importance of ensuring a comprehensive and transparent investigation. They also stated that they are in close contact with the Greek authorities to monitor the investigation’s progress.

The Deadly Catastrophe

In a recorded interview, one survivor revealed more about the days leading up to the boat sinking and the people drowning. After sailing for three days, the drinking water had run out, and thus the situation worsened due to thirst and hunger. When night fell, the passengers were informed that the Greek Coast Guard would come to rescue them. And indeed, a Greek ship did arrive and lay alongside the boat, tied it with a rope, and began towing it.

The ship moved at high speed, causing the boat to lose balance. When the boat leaned over for the second time, it capsized.

“When I found myself on the surface of the sea, I saw bodies around me and people screaming,” the young man said. “The situation was indescribable with fear and horror. I swam until I reached the back of the boat to search for my cousin and his friend.”

Afterwards, the young man swam towards a Greek Coast Guard boat and managed to climb aboard. Then, he reached the Moria camp with the rest of the survivors.

Ahmad ( 20), one of the survivors we met, fled from Syria to Lebanon at the end of March last year. He also described how the coast guard tied the boat with a rope and tried to pull it, and how the boat started tilting to one side due to the speed of the other ship. After that, the ship moved away, producing another wave that led to the boat’s capsizing.

Syrian Smugglers

Behind the scene of the boat sinking, there are people on the Libyan shore who are part of a closed network of brokers and smugglers benefiting from irregular migration from Libya to Europe. Their role begins when the migrants arrive on Libyan soil, whether by land or air, until the moment they board the worn-out boats and fishing vessels for the sea journey.

Four survivors mentioned that a Syrian man named Abu Nabal, from the town of Sahwa in Daraa, received them at Benina International Airport in Libya. Abu Nabal plays a crucial role in receiving the migrants, placing them in warehouses and detention centers until the time of departure.

He deals with refugees and migrants especially at Benina International Airport, where he uses his influence to facilitate their exit from the airport and avoid security checks. He uses a refrigerated truck to transport migrants from the gathering place to the launching point of the boats that eventually takes them to their intended destination.

Abu Nabal transfers the migrants with his car and gathers them at a specific location called: Al-Hangarat. Such places are usually located on the outskirts of Tobruk and have security guards. The migrants are prepared for the upcoming journey and provided with the necessary travel arrangements.

Abu Nabal works with two Libyan smugglers as middlemen, and the amount that each migrant pays reaches up to $3500 per person.

According to the survivors’ testimonies, Abu Nabal requires the migrants to pay him to facilitate their journey and deliver them to the main smuggler. The amounts vary according to the services provided, ranging from $300 to $500.

The investigation team listened to recorded audio clips between the family of one of the missing Syrian victims and a Syrian broker, who has been residing in Tobruk for over 10 years and is working for a network of smugglers involved in filling up boats with migrants for $200 per person. The broker attempted to evade responsibility for the sinking of the boat.

“We told everyone that this journey is a journey of life or death,” he loudly told the family. “Everyone was informed about this. And you already know that many people die at sea. It is not a tourist trip. You cannot blame me for their deaths. I was just a means of communication with the main smuggler, and you linked yourselves to him.”

The family told the investigative team how the broker informed them that the ship’s captain contacted the broker and informed him of their arrival (in Italy). He also told the broker that he used a satellite phone, Thuraya, to communicate with the authorities for their rescue. The captain also told him: “I will throw away the phone, so that the authorities won’t recognize me!”

Youssef now finds himself on the Greek coast. He arrived there on a Greek rescue boat with other survivors. He still remembers the scene and believes it will never leave him for the rest of his life.

“When the boat capsized, people held onto each other,” he said. “I swam away from them. And when the coast guard directed searchlights at us, while we were in the water, I had a watch in my hand. The time was 2:05 am. I continued swimming towards the Greek rescue boat, and when I reached it, it was 4:15 in the morning. I swam for two hours and fifteen minutes. It was June 13, and my watch was still working, even in the water.”

Failing to provide assistance in cases of maritime distress is a crime that is accountable under international law and Greek law. It is necessary to conduct a comprehensive and transparent investigation to determine the facts and hold those responsible accountable. The European Court of Human Rights has previously condemned Greece in similar cases, which only confirms the need to conduct a proper investigation and adhering to all applicable laws.