There, the threats arising from the pandemic are exacerbated by the feeble infrastructure and lacking medical equipment, which make the spread of the virus in the region unlike its spread in any other place around the world.

Throughout the region, there are 1,000 camps, accommodated by medical centers that have 1,689 inpatient bed capacity — that is one bed per 2,378 people. There are also 243 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds, each to accommodate 16,534 people, 107 ventilators, each to serve 3,7549 people, and 32 isolation units, where each unit is dedicated to 125,554 people.

The first confirmed case was announced as of a Syrian doctor, who constantly travels from/to Syria and Turkey by virtue of his work. However, the puzzle pieces were not all in place as to ascertain whether the doctor’s was in fact the first positive case, or that north Syria did actually record, but not announce, cases before him. Equally uncertain is whether that case had carried the virus from Turkey or had contracted it in Syria.

Therefore, this investigation seeks to track COVID-19’s infiltration into north Syria and the ensuing confirmed cases. The investigation’s scope, nevertheless, is not limited to monitoring the movement of people through border crossings with Turkey, but it also reports the daily two- way traffic of Turkish employees, who travel to areas in north Syria, and people who might have carried the virus from other Syrian areas into the target region, that is north Syria. Furthermore, the investigation reports that the measures adopted at the Idlib-based Bab al-Hawa and the Aleppo-based Bab al-Salameh border crossings between Syria and Turkey were not feasible enough to ensure that the virus is not transmitted across the borders, according to medical reports and locals’ accounts, who have been tested in an assessment of potential infections.

Indeed, the first confirmed case came from Turkey. But the northern regions of Syria share borders with areas held by the Syrian regime too, and others controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The latter two regions have recorded positive cases that pre-date the spread of the virus in north Syria.

Seeking to curb the pandemic’s spread, most nations across the world imposed restrictions on travel by land, sea and air. They either completely closed crossings and airports, or conditioned passengers’ movement, who were asked to undertake the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test that proves they do not have the virus.

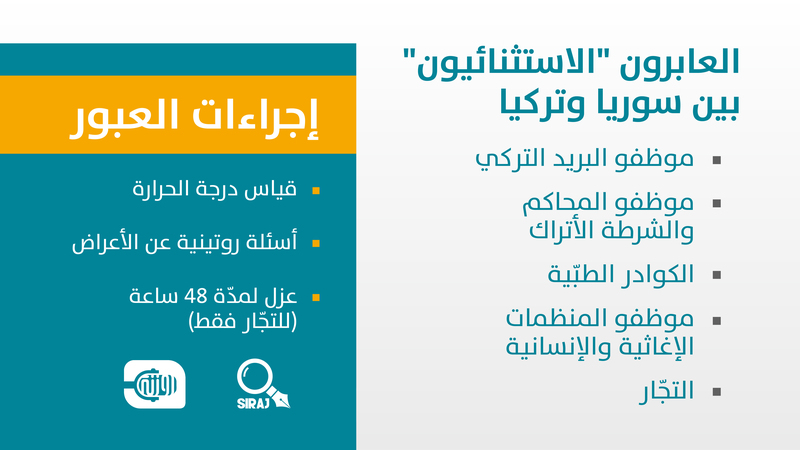

The Syria-Turkey border crossings followed suit and adopted similar measures. They were completely closed, banning in and out movement as of mid-March, a few days into the virus’ spread in Turkey, according to separate statements made by the Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh crossings. Nevertheless, the closure decision had some exceptions, as it allowed certain groups to travel back and forth, while conducting no smear tests to ascertain they are not carrying the virus. That puts both countries at the risk of potential outbreaks, if borders were crossed by asymptomatic passengers, who might have contracted the virus in either of the countries.

On the condition of anonymity, an employee of a Gaziantep-based Syrian relief organization reported that lesser travel exceptions were granted during the pandemic, only a quarter of relief organization staffers, compared to the pre-pandemic figures, were allowed access. However, these continued to travel over the course of the pandemic through the Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh crossings. Moreover, when dealing with the exceptional passengers, the measures adopted at the crossings were a matter of “formality”. On the Syrian side, for example, the measures were limited to temperature assessment and a few routine questions, asking passengers whether they had any of the virus’ symptoms, the employee added.

Travel exceptions are granted to

Turkish postal service (PTT) employees

Turkish policemen and court employees

Medical staffers

Relief and humanitarian organizations’ employees

Merchants

Cross-border travel measures

Temperature assessment

Symptoms-related routine questions

48-hour self-isolation, imposed on merchants only

Such travel exceptions are granted by Turkey to Syrian doctors all the time, allowing them access through Bab al-Hawa, north of Idlib, and Bab al-Salameh, north of Aleppo, under a single condition, that doctors coming from Turkey or Syria get their temperature assessed. Merchants, holding the Turkish state-issued card, are also allowed access through the borders, however, on the condition of committing themselves to a 48-hour quarantine before moving in and out of Turkey, as well as getting a regular smear test, according to the same source.

This case also applies to Turkish employees, operating in the Olive Branch and Euphrates Shield areas, whose work dictates that they travel in and out of Syria on a regular basis, an officer of the Syrian Civil Police in the Euphrates Shield area said.

From border areas, such as Hatay, Turkish employees arrive in Turkey-run Syrian areas, heading to the branches of the Turkish postal corporation, police departments and courts there. Even though these employees do not mix with Syrian civilians to a large extent, they get in touch with Syrian colleagues, according to the civil police officer. This turns the exact date of the virus’ entry to Syria into a subject worthy of investigation, along with the maintained safety procedures and health protocols regarding social distancing, the one-meter distance rule, wearing masks and gloves, and placing hand sanitizers in the workplace.

As of mid-July, the Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh crossings have “officially” announced resuming traffic in and out of Syria, while adhering to “preventive measures”, after an official closure that denied civilians travel through the crossings since mid-March. Nevertheless, the preventive measures maintained by the crossings throughout the lockdown were described as “irresponsible and negligent” by an employee of a relief organization, based in southern Turkey. He recounted his experience with these measures, having travelled through the crossings regularly while they were officially closed. The source was tested himself, presenting an example of the border crossings’ mitigation policies which apply to other cases too. “Humanitarian organizations obtain an exception from Turkey, which allows employees to travel from/to Syria and Turkey once a month,” he said.

“It took us a temperature assessment only to be allowed to pass through the crossing. No other measures were maintained. Upon returning to Turkey, the same procedures were carried out. What strikes me as strange is that before arriving into the Turkish crossing, we were let into a cooled room on the Syrian side of the crossing. There, our body’s temperature cooled off, since we had to walk for about 15 minutes at the Bab al-Hawa Crossing,” he added, explaining that if any of the people granted the travel exception contracts the virus, he /she will not be certain about its source, whether it is Syria or Turkey.

“Specialized teams were sterilizing all the crossing’s facilities and the buses that transported passengers to and from Turkey, in addition to sterilizing the departure centers. Furthermore, aboard free buses, social distancing was maintained between passengers, who were asked to wear masks and gloves,” Mazen Alloush, director of the Public Relations Department at Bab Al-Hawa Crossing, responded.

In the past few months, he added, they also established two medical posts in cooperation with the Syria Relief and Development Organization (SRD), one near the departure station and another at the entrance to Turkey. Doctors and nurses at the posts are assigned addressing the affairs of passengers travelling from/to Turkey only, applying measures such as assessing body temperature “only” and having them answer routine health-related questions. If passengers display COVID-19 symptoms, they are isolated and then transferred to quarantine facilities outside the crossing.

Coming from regime-held areas

Border crossings were not the virus’ only gateway to north Syria. The situation was the same at inside-Syria crossings, which demark the control areas held by the de facto authorities there.

On July 25, the Infectious Disease Surveillance Laboratory announced recording the first COVID-19 positive case in the city of Sarmin, east of Idlib. A source close to the confirmed case reported that the 60-year-old infected woman, originally from Sarmin, was in the Syrian regime held areas and had to resort to illegal means to return to north Syria as internal crossings were shut down due to the outbreak. On August 10, the Epidemic Early Warning Alert and Response Network (EEWARN) recorded a second case, however, in the city of Darat Azza, west of Aleppo, which also came from the areas controlled by the Syrian regime. This is thus sufficient to prove that a number of the positive cases have carried the virus from the regime-held areas to those controlled by the opposition, even though the crossings between the two sides were back then closed.

Muhammad Atallah said he was smuggled from the regime-held areas to north Syria, providing an account of his journey. “I lived in Lebanon for over seven years and had to return to Syria upon losing my job. I attempted entry through Turkey several times, but it did not work due to the visa. I was left one choice, passing through the Syrian regime’s control areas to reach Idlib province, my place of birth.”

“After I arrived in Aleppo, I stayed there for more than two weeks. There was no way to reach Idlib since the borders were closed for passengers by the opposition, fearing COVID-19. I had to seek smugglers. To get in touch with smugglers, my relatives told me that I should go to the bus terminal, where I will find them calling: ‘Idlib, Idlib!’ When I got to the bus terminal, I met a smuggler who appeared to be a fighter because he had a military outfit on. He presented me with the trafficking routes, adding that each would cost me a different price. The price reflects the level of comfort the passenger intends to enjoy. ‘If you do not wish to walk; you will be transported by a car for a couple of hours. This will cost you over $700 (about 1.5 million Syrian pounds). However, if you choose to take the Jabal al-Ahlam/ Mountain of Dreams road, where you have to walk for over two hours, you will have to pay $200 (420, 000 Syrian pounds), and it is not intended for families’,” he added.

“After agreeing to take the Jabal Al-Ahlam road, we got on a bus, 10 of us, planning to reach the city of Nubul in northern rural Aleppo by evening. From there, we were next transported to a village in rural Aleppo, called Burj al-Qas, on a different bus, and then to the Brad village. Finally, we had to take the Jabal al-Ahlam road on foot which led us to the city of Afrin, rural Aleppo. It took me a few hours to arrive in the city of Idlib. Fearing to transmit the virus to my family in case I had it, I isolated myself at home for a week, until I made sure that I had none of the COVID-19 symptoms.”

First case – track tracing

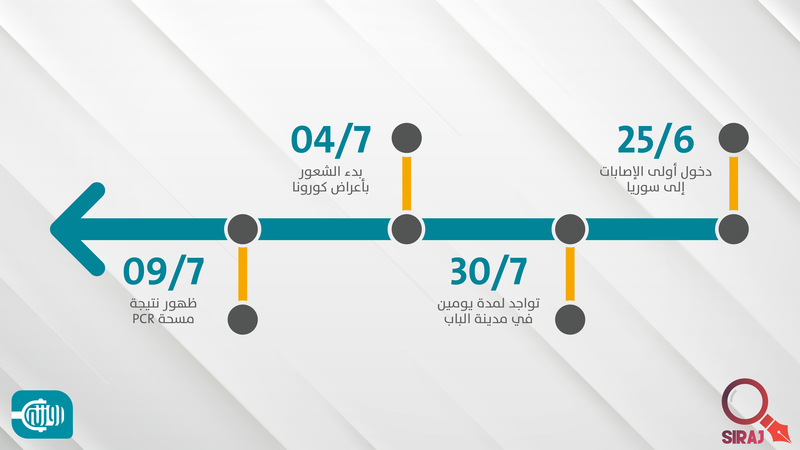

On June 21, a Syrian doctor entered north Syria through the Bab al-Salameh crossing. Less than ten days, on July 4, he began to feel COVID-19 symptoms, according to a medical source close to the doctor. On July 9, the tests proved he was positive for the virus. It has not been determined whether the doctor carried the virus with him from his residence in Gaziantep, Turkey, or had actually contracted it upon his return to Syria, for the virus’ incubation period is 2-14 days, said the Gaziantep-based doctor Yasser Farouh, a staffer of the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU). “In both cases, what to blame is the measures adopted at the crossings, which they keep as a matter of ‘formalities’, when addressing the disorder caused by travel exceptions,” he added.

On July 5, the infected doctor isolated himself in his residence at the doctors’ dorm of the Bab al-Hawa Hospital. He also underwent the PCR test two days later. The results came out on July 9, proving he tested positive. The Idlib Health Directorate, for its part, placed the Bab Al-Hawa Hospital under quarantine, including medical staff, inpatients, and clients for five days. Following this, it confirmed that all test results were negative.

Before he was tested, the doctor stayed in al-Bab city between June 30 and July 1, visiting a relative who works in the al-Bab Hospital, where he could have possibly contracted the virus from a patient or a colleague in Syria, especially in the city of al-Bab, a doctor of the Idlib Health Directorate said on the condition of anonymity.

Furthermore, on July 7, an inside medical source from al-Bab Hospital reported that a new COVID-19 case had been recorded of a non-resident Turkish doctor in the hospital. The case was not officially announced, neither by the Ministry of Health in the Syrian Interim Government, nor by the Turkish government.

According to the source, the doctor is in charge of an ambulance and patients referred to Turkey. He carries out weekly shifts in the hospital and moves between the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch areas. This means the stakes are high that other people in areas of north Syria are already infected, given the geographical scope of the Turkish doctor’s movement.

June 25

Fist case enters Syria

July 4

Feeling the Symptoms

July 9

PCR test results

July 30

Staying in al-Bab City for 2 days

Following the first infection, several other COVID-19 positive cases were recorded in north Syria, all of them are medical personnel, who may have had contact with Turkish doctors or Syrian patients at their workplace. On August 10, a second Syrian doctor tested positive — a pediatric surgeon at the Hand in Hand Hospital in Atma town in northern rural Idlib. The newly confirmed case prompted the Idlib Health Directorate to place the hospital under quarantine, with all the people inside it. On the same day, a third positive case was recorded, of an oral and maxillofacial surgeon at the Bab al-Hawa Hospital, who was quarantined at the doctors’ dorm of the hospital, according to one of the hospital’s administration officers.

On July 11, an infection of one of the staffers of the Emergency Department at the Bab al-Hawa and al-Shifaa hospitals in Idlib city was reported. In response, the Health Directorate quarantined the second hospital’s personnel, but it failed to identify the infected persons, which is likely to allow for a large outbreak in Idlib, a source of the Idlib Health Directorate noted on the condition of anonymity.

As the COVID-19 spread map grows larger, the threats arising from the underequipped medical sector in north Syria will continue to increase, for “the measures plan to combat the virus, if the region is to suffer a spike in cases, are modest because they depend on hospital equipment and manpower readiness,” Doctor Muhammad al-Salem said.

Doctor Muhammad al-Abrash, for his part, said that the Health Directorate has provided tests, but the number is still insufficient to cover the population throughout north Syria. “A number of ventilators were secured and three isolation and recovery hospitals were constructed. However, these are not enough, for there are only about a 100 ventilators in north Syria,” he said. “For the time being, hospitals are obliging staff to maintain preventive measures, which have not been properly withheld so far.”

On September 5, the date of reporting, the positive case number mounted to 98, whereas 66 cases were recorded as recovered, according to the ACU. As a mitigation mechanism, the health directorates in the region are tracing contacts of the confirmed cases and testing them for the virus, enforcing no further restrictions, however. The people, on their turn, continue to violate safety and preventative measures, particularly social distancing.

This investigation is hosted by the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ) and Radio Rozana.