By: Musab al-Shehab

Urfa, Turkey, Jan, 2016, (Al-Arabi al-Jadid) –When he taught at the informal Ghiytah Mater school, funded by volunteers in the Turkish city of Urfa, his monthly salary did not exceed $30. However, Osama’s salary increased six fold to $225 at Al-Ikha School., though only for a while.

“I was caught between two fires: My livelihood on the one hand and my students who became attached to me on the other hand,” Osama said.

His ordeal began when he left the financially-unstable Ghiyath Matar (elementary/secondary) school, founded by Syrian volunteers on the 1st of October, 2013.

“They used to pay us 200 Turkish liras ($90) for three months while I paid 550 liras ($250) a month for rent, excluding other expenses,” said the teacher who holds a degree in physics. “This sum is next to zero,” added the father of three.

Al-Ihsan (now Al-Ikha) school took in Osama on 20/3/2014. There, he found a better opportunity to work with a Kuwaiti donor financing the school, paying 500 liras ($225) as a minimum basic salary for every teacher. However, five months later, the Kuwaiti donor stopped paying without giving his reasons, and Osama along with 24 other teachers lost their pay.

Osama is one of many teachers facing such conditions in volunteer, donor-funded schools.

The author of this investigation organized a survey in Urfa, home to about 500,000 Syrian refugees, covering 67 Syrian teachers in three volunteer schools (Bila Hudud, Al-Bahaa, and Obeida AL-Hamoud). The schools have nearly 1,500 students out of 100,000 school-aged Syrians in Urfa and its countryside, who had fled the war in their country.

Turkey hosts half a million school-age Syrians, who account for a quarter of the total number of Syrian refugees in Turkey, home to 250 Syrian schools according to estimates by the Turkish government. Only one of five of these children is enrolled at school (Figure-2 quotes) The survey shows that 46 percent of teachers would leave their profession if they can get other work at a fixed salary, which is not possible to have in these schools. Around 20,000 teachers work in Syrian territories outside the control of the regime, while the number of Syrian teachers in Turkey stands at around 5,000.

Over ten months of investigation covering eight schools in Urfa, the author concluded that all these schools (Sirine 1, Sirine 2, Bila Hudud, Al-Bahaa, Al-Ikhaa, Obeida al-Hamoud, Al-Fajr, and Ghiyath Matar), which have more than 3500 students and 200 teachers combined, do not pay fixed salaries but small “bonuses” that vary from school to school. The wages come either from donors, relief groups, religious groups or international organizations.

In truth, there are no clear regulations for establishing volunteer schools in Turkey, while the Ministry of Education of the Syrian regime observes 67 different articles and 150 provisions as conditions to license private schools and nurseries in Syria.

Five out of the eight schools in Urfa are not subject to any educational law. They have no permits to operate and do not report to any official authority, be it Turkish or Syrian. The rest (Sirine 1, Sirine 2, and Bila Hudud) abide by Turkey’s Education Law.

The elementary certificate examinations are nonstandard. Each school has its own format, unlike the situation in Syrian areas controlled by the regime. The Turkish Ministry of Education seems indifferent, while donors have a “seasonal” approach to support, and the Ministry of Education of the Syrian interim government is complacent.

Students who cannot read or do arithmetic

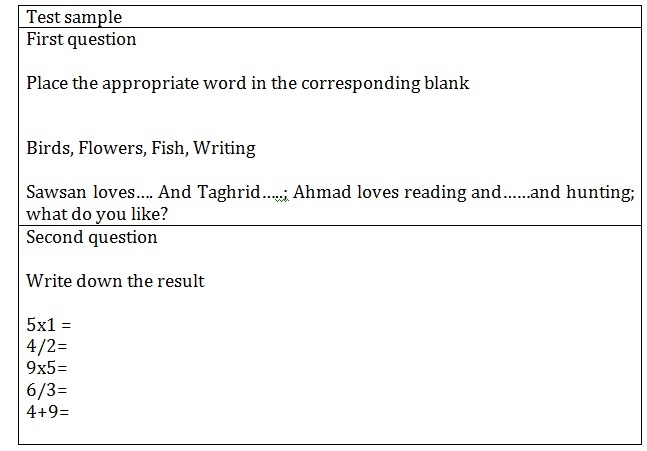

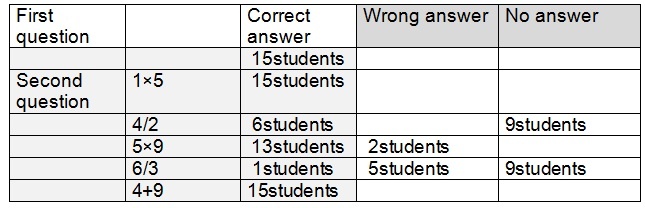

At Al-Bahaa School, which collects nominal fees of 50 liras ($22) per month from every student, the journalist tested 15 students, in third grade, to assess their educational attainment in the absence of job stability for the teachers. Only one student passed the aptitude test.

At Al-Bahaa volunteer school in Urfa, on the 3rd of October, 2015, he tested at random 15 third grade students. He used a written aptitude test prepared by an education expert with ten years of experience in teaching at primary schools in Aleppo. Mohammad Saleh, who holds a degree in education, believes the test is simple and would be easy to a student studying the official curriculum of the Syrian interim government.

After the 30 minute test, the results were as follows:

9 out of 15 students failed to answer correctly 6/3. One student of the remaining six answered correctly and passed the test

In these eight schools, the curriculum taught is the amended Syrian curriculum issued by the Ministry of Education in the Syrian interim government. It is distributed free of charge. The curriculum was developed in 2013 to remove any reference to the regime and its followers, said Dr. Abdul-Rahman Kawara, executive director of the Syrian Education Commission in an interview on Al-Aan TV. Although the curricula were unified, orientations change from one school to another. Schools funded by Turkish religious endowments promote more conservative climates, in terms of separating the sexes and implicitly imposing the headscarf or certain dress codes by refusing to enroll girls who are bareheaded without stating a reason. Other schools seek to emphasize a certain identity and separate supporters and opponents of the Syrian regime, refusing to enroll loyalists.

The journalist established that eight schools are financially unstable, having been established by Syrian volunteers without proper administration. Two schools — (Ghiyath Matar and Al-Ikha) — are funded by Syrian donors and other private sources. The other two (Obeida al-Hamoud and Al-Bahaa) collect nominal fees from the students (50 liras/$22) paid for one time only at the first school. As for the second school, fees are collected monthly.

The four stable ones: Two are funded by UNICEF, one is funded by Turkish endowments and the fourth is funded by the Syrian Al-Ataa Relief and Development Organizations, which receives support from Arab organizations. The first three schools are administratively under the supervision of the Turkish Ministry of Education.

The role of the interim government

Around 73% of teachers surveyed in our poll held the interim Syrian government, based in Gaziantep, Turkey, responsible for not paying their salaries and for neglecting their rights.

The term “volunteer” (without formal rights) has been associated with Syrian teachers in Urfa-based so-called “volunteer schools”. These are divided into two types: Formal schools that answer administratively to the Turkish Ministry of Education and funded by Turkish endowments and UNICEF. And informal schools, which have no permits or administrative supervision and are established by Syrian volunteers with support from donors and humanitarian groups. Some are self-funded through nominal fees collected from the citizens.

Syrian schools without supervision

During the field research, the journalist found out that the Syrian schools in Urfa had no links to the Ministry of Education in the Syrian interim government. This is true for all schools in Turkey, according to Azzam Khanji, director of the Ministry of Education in the interim government.

Conditional support and discrimination

Although monthly bonuses are paid, Anas Awf, deputy director of the Bila Hudud school (funded by Turkish endowments and answering to Turkey’s Education Ministry), said they are not enough compared to what is paid to Turkish teachers who are paid up to 10 percent more than their Syrian counterparts and have official work contracts.

The Turkish endowments, which are not lacking in financial resources according to Awf, funds the Bila Hudud school established by Syrian volunteers in April 2014. It was then expanded in February 2015 and now comprises four schools covering all stages of school education, according to Awf.

The endowments pay 8.5 liras ($3.5) per hour to teachers as bonus. Syrian teachers thus earn 650-800 liras ($270-330) for 80 to 95 hours per month.

This equation does not apply to teachers of Turkish Language who are Turks. They earn 9.5 liras ($4) per hour and get many times more the working hours with a minimum of 160 hours per month. They also benefit from health insurance and end of service compensation, in addition to pension salaries, and have official work contracts.

On the other hand, Syrian teachers sign a ceremonial contract of “moral commitment” with the Ministry of Education in Turkey. The contract states that the work is on a volunteer basis, with no obligations on the first party: no health insurance or salary from the ministry. Only bonuses are granted, regardless of the source.

Teachers are not allowed to object or claim compensation if they are fired. This happened to 25 teachers who were sacked from Bila Hudud on September 2nd, 2015 without the reasons being stated. At the end of the first semester, they were told to join the second semester — but that they had to wait until they are called. They were never called, and new teachers replaced them, according to an administrator at the school who asked not to be named.

Moreover, the Ministry of Education imposed the appointment of a Turkish coordinator in the Bila Hudud schools. He received 3,000 liras a month ($1250) while a Syrian deputy received 850 liras ($350) from Turkish endowments.

This reporter conducted a comparison between three Syrian schools, Bila Hudud, Al-Bahaa, Obeida al-Hamoud; and the Iraqi Nineveh School which is subordinate to the Iraqi Ministry of Education. The Iraqi school was opened on 1/11/2014 in the city of Urfa, attracting 17 specialized Syrian teachers, all degree-holders. These teachers include Osama, whose conditions improved after he started earning 1400 Turkish liras ($635) monthly.

The comparison shows that the three “volunteer” schools only pay their teachers bonuses: one—$330 monthly as a maximum; the second $160 per month; while the third paid $600 for the entire scholastic year.

In the Bila Hudud school, there are 620 students. Each bench seats 3 to 4 students, while the number of total students in Al-Bahaa and Obeida al-Hamoud is 850. Sometimes, a single bench could have 8 students at Obeida AL-Hamoud school.

On the other hand, every student has his own desk in the private school, which has only 75 students. This school hires specialized teachers who are paid a minimum of $400 per month.

All volunteer schools have teachers who never worked in teaching before or who teach outside their fields (between 7 and 39 percent of teachers in the three schools).

Timid assistance

In February 2014, the Ministry of Education in the Syrian interim government printed 2 million books free of charge as a step forward for all academic levels, to cover the needs of 200,000 students – 80% for schools in liberated areas and 20% for Syrian schools in neighboring countries, according to Dr. Abdul-Rahman AL-Haj, adviser to the Interim Minister for Educational Affairs.

The interim government also announced on its official page on March 28th, 2014, that $1.5 million has been disbursed to cover six months’ worth of salaries to teachers working in Syrian provinces.

طHowever, the government has only spent $1 million out of the declared sum over one month, Azzam Khanji, director of the Education Ministry (interim), said in an interview.

“When the decision was issued, I noted to the ministry that the sum is not enough to cover six months and 20,000 teachers inside Syria.Each teacher would get 10,000 Syrian pounds ($50), which means they need $6 million in six months. Thus, a single payment was handed out in some provinces and in others two payments of 5000 Syrian pounds ($25)”.

He justified the reduction of the sum by saying: “Some areas have no schools left in them as a result of the battles raging there.” Nevertheless, he admitted to failing to properly announce the reduction, saying it was an unintended mistake. Khanji added: “Some ask what happened to the rest of the money? We say it went to the summer offset project” in reference to free lessons in all subjects lasting 2-and-a-half months, starting in July 2014. The project targeted students who missed academic years and new refugees.

Nour AL-Din Mahamid, the official who follows up educational departments in Syria, said 41,700 students benefit from the project in Turkey, Lebanon, and the Syrian interior.

At the same time, approval came to support troubled schools in Turkey and in other countries neighboring Syria with $100,000 monthly over a period of four months. The interim cabinet in May and June 2014 issued a decision allocating $200,000 (lump sum to all schools) to further support troubled schools in Turkey.

Although most schools in Urfa are considered financially-troubled, the Ghiyath Matar school was the only one to receive funding from this allocation, getting 7600 liras ($3450) to cover rent for four months, onApril 22nd, 2014.

No supervision

Kinda al-Rawi, a volunteer, is the director of Ghiyath Matar school. She was suspended in early 2015 from her post as representative of the Ministry of Education in Urfa, for reasons unknown to her.

Kinda said: “Education without government support may continue, but haphazardly.” She added that “there is a lack of supervision over these schools. Teachers can close the door to students and impart on them his/her ideas, and when bonuses are not available only teachers with other sources of income step forward, which means we have to overlook credentials.”

Kinda stressed that volunteer schools have lost many skilled teachers because of the lack of stable wages. This includes her school, which was left by six specialized teachers in the first 5 months after the school was launched. Someone told her: “I would rather carry stones than continue to teach.”

Strike

On December 12th, 2014, two schools went on strike in the city of Urfa (Al-Ikha and Obeida al-Hamoud) in protest at “the failure of the interim government toward troubled schools and teachers who do not receive wages”. Um Tahsin at Obeida al-Hamoud, held a banner, along with her students outside the school, demanding wages to be paid. Although Obeida al-Hamoud school collects fees from its 420 students, this is not enough to cover event rent, according to its director Ziad Mahidi. Mahidi. He said the fees are nominal, not exceeding 50 liras, and are paid once a year. “A large percentage of the students cannot afford the fees, and they are exempted.”

Neglect and empty promises

On March 19th, 2014, Iyad AL-Qudsi, deputy interim prime minister said in a statement published on the interim government’s website, that “the government has a plan to support all schools in Turkey, starting with those that are facing problems in meeting costs and not salaries of their teachers.”

However, Ahmad al-Qassem, director of the interim government’s office in Urfa, had a different opinion. “Those schools are private sector and are not actually subordinate to the interim government, but to donors. Hence, they are their responsibility.”

Qassem believes all sides are responsible for the failure, and blamed the former minister of education Muhyiddin Bananeh for most of the administrative failure.

This reporter found out that the Education Office does not have any allocations or a budget. The office of the interim government in Urfa has been corresponding with the ministry of education since December 2014 to resolve outstanding problems but to no avail.

On March 17th, 2015, the head of the Syrian interim government decided to close his government’s offices in Turkish cities, without giving reasons. A source in the Syrian National Coalition who asked not to be named said the main reason behind the closure of the offices in Istanbul, Urfa, Mardin, and Hatay is the inability of the interim government to pay the salaries of staff and other costs amounting to $72,000 a month.

Shortage in funding

On the morning of March 25, 2015, this reporter went to the Turkish city of Gaziantep, to meet with the Minister of Education Imad Barq. After waiting for more than half an hour the next day in a small room, the request for a meeting was denied “for reasons specific to the minister”, according to the secretary. The reporter’s insistence on the importance of getting official answers to clarify matters was ignored.

On the morning of March 27, the attempt was repeated with no result. On the advice of the secretary, the author headed to the office of the Education Department Azzam Khanji in the same building.

“Unfortunately, the Director of Education traveled to Istanbul, and will come back after a few days,” was the answer of his office manager. On March 31, the journalist met with Azzam Khanji.

We asked him why wages are not allocated to teachers in Turkey, similar to the teachers in the Syrian interior who were allocated $1.5 million over six months. He replied: “The total sum given to the interim government since its inception in 2013 was 50 million euros. The Ministry of Education was allocated only 8 million Euros. Even if the entire budget of the government is diverted to the Education Ministry, it won’t be enough.”

Khanji added that $90 million are needed to cover the educational needs of Syrian students in the liberated areas in Syria and in neighboring countries, including books and monthly grants to teachers.

Moral and ethical role

Khanji said the schools are under direct Turkish supervision (the Ministry of National Education) while the role of the Syrian interim Education Ministry was “moral and ethical”.

The Syrian official held the UN and other international organizations responsible for neglecting education. “We reached out to the known international organizations. They all say nice things about cooperation, but in the end, they want to get the information and deal directly with schools.”

Paragraph (2) Article (28) in the 1990 Convention on the Rights of the Child in paragraph states: “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that school discipline is administered in a manner consistent with the child’s human dignity and in conformity with the present Convention.”

Up in the air

In October 2014, the Ministry of Education in Turkey began including Syrian schools under its administrative responsibility. The ministry overlooked the financial aspects, which means schools remain in the same position, looking for sponsors to cover their expenses and the wages of their teachers before they go the same way Osama went.

Osama struck luck recently after he almost lost hope. The Iraqi Nineveh school became his lifeline. In March 2015, the Obeida al-Hamoud school was closed down after it was no longer able to meet its expenses.

This investigation was completed with the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) – www.arij.net – and coached by Saad Hatter. Before the completion of this investigation, Musab al-Shehab joined the convoys of Syrians boarding death boats to seek asylum in Europe.