Mohammad Bassiki – Ali Al Ibrahim – Chafak Kojak

Over a period of a year and two months, Noor (a pseudonym), a Syrian woman from the city of Douma – a formerly rebel-held suburb of Damascus – wrestled with the struggles of imprisonment in an Assad regime prison – “Branch 227” – in the center of Damascus, along with her husband and two newborn babies.

Noor’s ordeal began in April 2013, when a government patrol near the Al-Mezzah highway stopped their car on their way back from Jordan. The entire family was arrested while attempting to return to their hometown of Douma, which at the time was besieged by regime forces.

Noor recalls the events of that fateful afternoon and the beginning of her ordeal: “We had only been on the highway for a few minutes, when a police car started pursuing us… they started shooting at our car until it stopped. The driver ran away and hid amongst the orchards, but we weren’t able to run for long. I was tired from giving birth, and I had my children with me, so we were arrested.”

Noor continues: “When they took us into the [state] security branch, they started to threaten to take my children away from me, because ‘I did not deserve them and because I was a terrorist.’ I felt like I was on the verge of collapse every time they made that threat. I had a bottle of milk for my daughter in my bag, but my son was so scared he couldn’t breastfeed. I think the milk dried up in my chest, so I gave him a sedative until he slept while he was crying from hunger.”

Yet this episode would not qualify as the most painful experience that Noor and her family would be subjected to – for she could not envisage what would happen to them following the fifth day of their imprisonment.

“After five days in prison” Noor recounts, “an officer suddenly entered the cell and took my daughter. I started pulling her back from his hand and so he hit me on the face. I fell to the ground and he took her. I heard the sound of her cries as they put her in the car, and then he returned to take my son. I asked him only to allow me to feed him, but he refused… I suffered a complete breakdown. They took my children and I became fully convinced that I would never see them again, and that I would never leave this place. I entered a state of complete despair, there was no life left in me.”

The arrest of children under the age of eighteen, the deprivation of their freedom and their torture, has left an indelible mark on the fabric of Syrian society, in addition to the open wound that remains in the psyches of both the children and their parents. Indeed, it should be remembered that it was the arrest of children in the southern province of Dara’a by security forces in March 2011 that sparked the outbreak of protests across the country, which would soon transform into a devastating conflict which would result in the deaths of more than half a million Syrians.

According to the many testimonies and accounts reported by rights activists, the families of detainees as well as former security and police personnel, the arrest of Syrian children under various pretexts has been a mainstay of the Syrian war and continues up to the present day – whether due to their participation in protests, simply accompanying their parents when travelling and passing through military checkpoints, or when passing from regime-held areas to those of the opposition and vice versa.

According to such testimonies, the imprisonment of children has become a widely-practiced and normalized mode of conduct amongst regime security forces, intended to “render families subservient and pressure them, and create an atmosphere of fear” – in the words of Ahmed Qashit, a defected regime officer who previously served as an investigator in Damascus, and who witnessed many cases of children being arrested in Aleppo following their participation in protests.

This reality has prompted many calls for investigation. Over three months, a SIRAJ working group unearthed the cases of 23 names of children detained in government prisons on unclear grounds, after having conducted a series of direct interviews with the families and relatives of the detainees, in addition to examining the meticulous documentation carried out by both Syrian and international specialized monitors. Amongst these detainees are some who have been released, while the fate of others remains unknown.

Within the sample brought to light in SIRAJ’s investigation, these include children who had been arrested along with their parents or only their mothers between the period of April 2012 and May 2019; 17 males and six females, all under the age of eighteen. This is both in stark violation of international law (the Convention on the Rights of the Child) as well being in contravention of the Syrian constitution.

It should be noted that the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which came into effect on the 2nd of September 1990 and was ratified by the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 44/25, defines a child as “every person who has not exceeded the age of eighteen, provided they had not reached the age of majority beforehand as defined by applicable law.”

In June 1993, Syria ratified the Convention according to Law No.8 of that year, and the Convention subsequently came into force on the 14th of August 1993 – though with reservations regarding Articles 20 and 21 of the Convention (related to adoption) and Article 14, which stipulates a child’s right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Additionally, Syria also ratified two optional protocols annexed to the Convention, pertaining to the selling of children and their embroilment in acts of prostitution, pornography and armed conflict – as per Decree No.379 issued on the 26th of October 2002.

“My son was so scared he couldn’t breastfeed, I think the milk dried up in my chest. I gave him a sedative until he slept as he cried from hunger”, Noor a Syrian woman testifies about systemic torture in Syria’s Branch 227 Intelligence Cell

According to Mishal Shamas, a lawyer and member of the Committee for the Defense of Prisoners of Thought in Syria: “I personally witnessed the arrest of a number of children by the Syrian intelligence services [mukhabarat], and defended some of them in the Terrorism Court. In 2013 I represented a fourteen year-old boy from the Al-Midan neighborhood of Damascus. He was detained by the military police, and instead of sending him to court for his interrogation, a medical report was sent reporting that he had died in prison – with the alleged pretext being that he suffered a heart attack.”

Meanwhile, Samer Mansour, a public investigator serving in the central Syrian city of Hama, before defecting from the security corps in 2015, tells SIRAJ: “Children used to be arrested because of graffiti on walls, or for throwing rocks at security and police cars. This served as a pressure tool against the families, to try and get them to disclose the identities of older protesters. These were vacuous excuses whose real aim was to pressure the people.”

On the road

Over a period of 22 days, Mohammed (a pseudonym), a child from the city of Hama, was detained with his mother in the dungeons of a state security branch in the city of Aleppo.

Mohammed was arrested on the 23rd of May 2019, when he was travelling with his mother from the city of Hama to Al-Bab in the northern countryside of Aleppo, the latter remains under the control of the Syrian opposition. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), which closely followed the cases of detained children, informed SIRAJ that Mohammed was fortunately released later.

Yet Mohammed’s counterpart from the same province of Hama, Yasser (also a pseudonym for safety reasons), did not share the former’s luck. He was arrested in 2012 and has still not been released, and to this day, his family have no information about his whereabouts or situation.

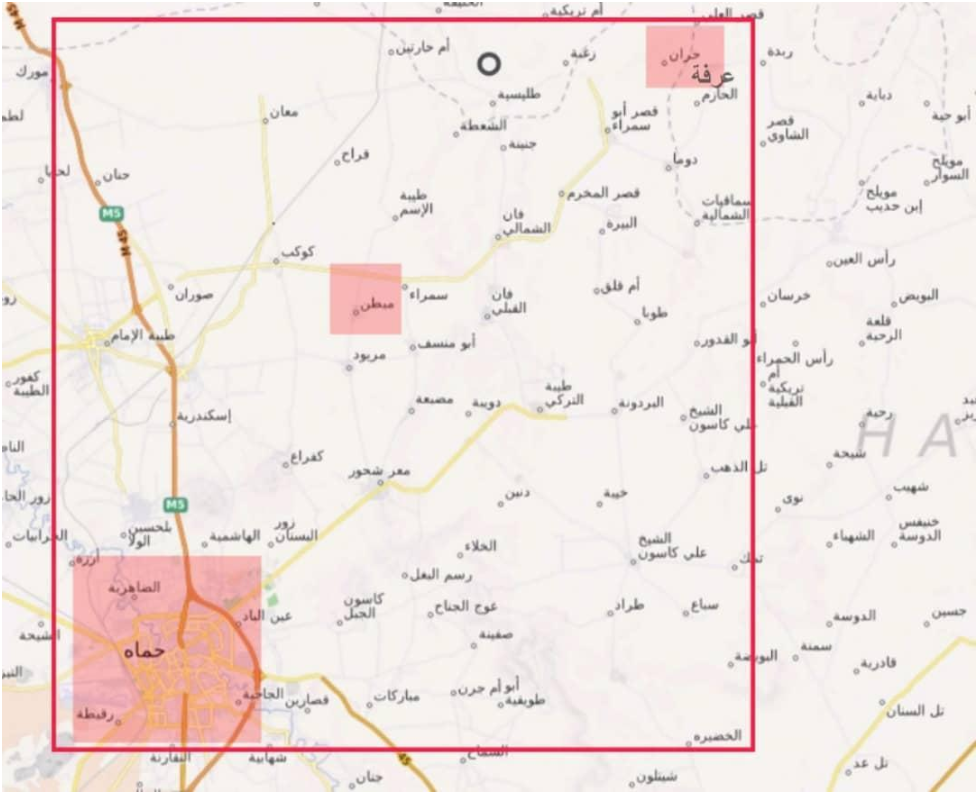

Sixteen year-old Yasser disappeared on the 10th of July 2012, after passing through a government checkpoint at Al-Mabtin east of the city of Hama. Yasser had been returning with his father from the city to his village.

Yasser’s brother, who refused to divulge his name for security reasons, spoke of the family’s suffering which began the moment of his brother and father’s arrest, and continues to this day. Like so many others, the fate of his brother and father remains unknown, with the last piece of information that the family received being that Yasser had been moved to Deir Shamil, near the city of Masyaf west of Hama.

Deir Shamil had previously served as a military camp for ‘vanguard’ (child) soldiers, before being transformed by the regime into a detention camp. Witnesses and survivors released from Deir Shamil informed Yasser’s brother that they “heard the voices of his brother being tortured in the adjacent cell.”

Despite remaining in the dark about Yasser’s fate, the brother’s attempts to uncover the fate of his sibling and that of his father have continued relentlessly – but to little avail. He says: “In the middle of 2014, a detainee was released from Sednaya prison, he told me that he saw my brother and father in the prison. Then in October 2017, I met a detainee from the village of Hawa in the southern countryside of Idlib, and he knew my dad and brother, and said that he had seen them in Adra prison (Damascus Central Prison).”

According to a 2016 report by Human Rights Watch (HRW): “Out of approximately 215,000 detainees held by the regime, there are no less than 1,400 children detained between the ages of thirteen and seventeen, while some defectors and witnesses have reported that there are detained children no older than eight years-old.”

HRW also noted in a 2015 report that it had verified the deaths of detainees held in places of detention, amongst them two children, one of whom was fourteen at the time of his arrest.

Under the roof of a prison cell

Despite her release, Noor is unable to escape the memory of those moments when she was forcibly imprisoned under the same ceiling with her son of only two months of age and year-old daughter. Yet even that harrowing experience paled in comparison with how her children would subsequently be wrested away from her possession, forcibly taken to a place unknown to her and which her jailors refused to divulge.

Noor recalls her feeling of helplessness when faced with such an unenviable situation: how could she answer a breastfeeding child’s cries for milk that she could not provide, and what does she tell her daughter who only wants to walk and play?

Noor recalls: “Me and the two children were in a room, and my husband in the cell. They took me into the interrogation room and they [the children] were crying form hunger. The interrogator told me to silence them, but my son would not, as it had been a long time since he had been fed.”

Noor adds that after the officer took her children away, she was moved to another room, and was placed with other women detainees where she would spend the majority of her imprisonment (a year and two months) at Branch 227.

A UN report read: “Syrian children were tortured and beaten with metal cables, whips, wooden sticks and electric shocks, [directed] even at their reproductive organs – in addition to having their nails ripped off, as well as the use of sexual violence.”

According to a report by the Violations Documentation Center in Syria (VDC), Branch 227, under the jurisdiction of the regime’s ‘military security’, is notorious for being “responsible for thousands of cases of arbitrary detention, forced disappearances and mass killing of dozens of detainees under torture since the beginning of the Syrian revolution.”

For its part, the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) – a Syrian Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) – extensively monitors violations taking place in the conflict. Going far beyond the discovery of child detainees in regime prisons, a SNHR report published in June 2019 on arbitrary detentions and forced disappearances in government detention centers, documented the killing of 177 children by torture, in what it described as a “crime of extermination.”

According to the head of SNHR, Fadel Abdel Ghani: “The regime has approximately 3,500 child detainees, with the majority forcibly disappeared with their parents knowing nothing about them.”

Indeed, Noor’s testimony affirms this reality, telling SIRAJ that “after three months of crying and asking the interrogators about her children, after they took them from her, the interrogator finally confessed that they held the children and did not hand them over to her family.”

Furthermore, in a 2016 report titled “Out of sight, out of mind”, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Syria (subordinate to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, or OHCHR) revealed the death of children as young as the age of seven under detention by the Syrian regime.

According to Abdel Ghani, the abuses committed by the regime against both the young and the adults are replicated against children – a demonstration of the regime’s failure and unwillingness to differentiate in the treatment of young or old, or provide an exception for children to be spared from the torture, killing and sexual violence practiced on their older counterparts.

Arrested for the guilt of others

Now in her forties, ‘Um Sha’ban’ – originally from the countryside of Damascus – today resides in a refugee camp near the city of Al-Bab north of Aleppo, having fled the capital with her three children, including fourteen-year old Yousef, who was detained for a year and three months after being arrested at a Syrian regime checkpoint in Damascus.

Yousef was arrested by the Al-Khatib security branch (‘Number 251’) in April 2012; he was seized because his father had joined the Free Syrian Army. The regime offered to release Yousef if his father surrendered himself – which he did a month later.

However, according to Um Sha’ban: “Despite my husband surrendering, Yousef remained in detention for a year and three months, and then was released.”

Hoping to understand the rationale underpinning a government arresting a child citizen because of the ‘guilt’ of their family, the team of experts and rights activists that we interviewed in the conduct of this investigation unanimously agreed that that the imprisonment of children in Syrian regime cells was primarily motivated by the aim of subjugating families who were known for adopting political positions against the regime, and ‘bringing them to kneel’.

The conduct of official Syrian regime authorities carried out via its security and military apparatuses, is a clear contravention of the second article (clause two) of the 1990 Convention on the Protection of the Child, which stipulates a child’s right to be protected from every form of discrimination or punishment derived from activities, expressed opinions or positions held by their parents.

Indeed, the regime’s arrest of children as a ‘pressure tool’ against families also violates its own constitution which was passed in 2012, specifically Article 20 which declares: “The state protects marriage and encourages it, and works to remove financial and social obstacles that hinder it; [the state] protects motherhood and childhood, nurtures [youth] development and young adults, and provides them with the appropriate circumstances to develop their talents.”

Meanwhile, the defected former investigator Ahmed Qashit adds: “The situation was [one of] crying and fear: I saw a child being hit with a cable on his back because he wrote slogans on a wall.” Qashit reaffirms that the purpose of this policy is to “pressure families and the population in general by abusing the young before [yet alone] the old; it was a matter of [official] policy, and instructions came from several ministries [ordering] for the use of repression.”

A seventeen year-old girl

With the Syrian regime having throughout the war adopted a policy of equal treatment for both sexes. Noor says she witnessed a number of female detainees under the age of eighteen, in addition to children of various ages. In her same cell, she noted, was a lady with three girls under the age of five.

“I saw a girl who was seventeen years-old and was diabetic” Noor recalls. “She suffered a psychological shock, and her diabetes deteriorated. When they took her to the hospital they refused to let her mother accompany her. She stayed there for three days, and when she returned she was in a state of shock. She didn’t eat or talk, and remained with her mother for twenty days before they left… I don’t know if that was to another [prison] branch or if they were released.”

Noor’s account is reinforced and corroborated by such detailed reports as that released by Amnesty International in 2016, titled “It breaks the human”, which affirmed that most former female prisoners had witnessed children in detention centers, including those who were being detained with their mothers.

As mentioned, children are not only detained in inhumane conditions, but are also subject to torture – as reported by human rights groups and as declared by a detailed investigation published in 2014 by the United Nations Secretary-General to the UN Security Council (UNSC).

The UN investigation concluded that children were arrested at various places, from checkpoints to homes, schools, roads and hospitals, notably in the provinces of Dara’a, Idlib, Homs, Deir al-Zor. The report stated that the majority of the detained children were held in the same detention cells as adults, while adding that children as young as the age of eleven were subject to severe mistreatment, including torture, in order to extract confessions, humiliate them, or pressure their relatives to surrender themselves or confess to alleged crimes.

The UN report read: “Children were tortured and beaten with metal cables, whips, wooden sticks and electric shocks, [directed] even at their reproductive organs – in addition to having their nails ripped off, as well as the use of sexual violence.”

The imprisonment of children has become a widely-practiced and normalised mode of conduct amongst Syria’s security forces for its effectiveness in “rendering families subservient and creating an atmosphere of fear”, Ahmed Qashit, a defected officer states.

In a statement made to the Syrian website Zaman al-Wasl, the General Secretary of the ‘Syria Justice Gathering’, Judge Mohammed Noor Hamidi, declares: “International law forbids warring parties from deploying sexual violence against children, and governments must pursue all of those who violate these agreements, including the Fourth Geneva Convention, and the supplementary first and second protocols, as well as the conventional laws that operate in all conflicts.”

Hamidi adds that “sexual violence is amongst the most heinous of human rights violations [practiced] by the regime, and many cases have been documented in regime security branches that practices sexual violence against children and women in order to force them to confess to crimes that they did not commit.”

According to Qashit: “We saw children being transported in police cars, ranging between the ages of seven and ten, being physically restricted and sprayed with gases, beaten with plastic parts, and their hands placed in metal restraints before being taken for investigation.” He adds: “The children were subjected to all forms of torture, including beatings on the back and stomach, until they were placed in isolation cells. They frightened them, telling them things that were not suitable for their age.”

Children in Sednaya

Since the fifth of January 2013, the parents of five children from the village of Tesneen in the northern countryside in Homs have remained oblivious to the fate of their children, after they were arrested and forcibly disappeared following an incursion into the village by pro-government forces and allied militias. Tesneen had a population of four thousands residents, and has witnessed the killing of 105 individuals, including women, children and elderly – in addition to the arrest of a large number of locals, including the aforementioned children whose ages ranged between ten and thirteen.

One family source who was witness to the events speaks of the family’s continued daily suffering, especially the parents, who remain in the dark about the whereabouts of their detained children, despite their continued unremitting search. However, some information has emerged suggesting that they may be held in the infamous Sednaya prison of Damascus.

According to the family source, who spoke to SIRAJ on the condition of anonymity: “We tried a lot… the search is continuing in the chance that we discover a glimmer of hope. We tried to get in touch with anyone who was released from the regime’s jails, and we appointed lawyers, but to no avail.”

Undoubtedly, the most haunting question relentlessly circling in the minds of the family is whether their children are still being held in the Syrian regime’s prisons, or whether they may have been executed. The family source has asked himself the same question, and answers: “Their disappearance amidst a complete lack of knowledge about what has happened to them has left us in a state of anguish and pain, to the extent that some mothers have been unable to internalize what has happened, and have succumbed to psychological illnesses.”

Life after imprisonment

The Tesneen family source’s details of the suffering of children’s family is bolstered by the account given by Taher Laila of the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), where he works as a team leader for psychological and social support. In conversation with SIRAJ, Laila spoke of the psychological difficulties incurred by child detainees in the aftermath of their experience, stating: “The experience of imprisonment is difficult, not least because a child’s psychological make-up is more fragile than that of an adult, meaning that the impact is deeper.”

Laila details some of the psychological and social aftereffects which child detainees are left with: “[Imprisonment] causes the child anxiety, depression and isolation; their social relationships with those around them can be damaged and become dysfunctional. Furthermore, the child can suffer post-shock trauma, whereby images of the experiences they encountered can be repeatedly evoked, which can affect their sleep and functionality in all aspects of life.”

Such a diagnosis accurately describes the experience suffered by Noor’s two children, after the family was released following a year-long imprisonment as a result of a prisoner exchange between the rebel faction Jaish al-Islam and the Syrian regime. On her release, Noor’s now-two year-old daughter “could not reacclimatize with those around her, and was always crying.”

Noor expands: “My family used to [affectionately] tell her ‘your uncle is coming soon to take you for a trip!’, but she’d cry more and scream. Later my family discovered that she was afraid of the word ‘uncle’, and they found cigarette burn marks on her feet. Perhaps there was someone in the prison who scared her who was called ‘uncle’, and for a long time she remained afraid of that word.”

According to Noor, her daughter started to fear all men – to the extent that any time a relative tried to carry her she would become terror-stricken. Twenty days after her release, she recognized her mother, but was initially too afraid of getting close to her father.

Blaming oneself

On the other hand, another widely-reported psychological phenomenon in former child detainees is the feeling of self-guilt, whereby it has been found that the detained children later develop a strong propensity to blame themselves for their experience. Um Sha’aban’s son, Youssef, was one such obvious example – after his imprisonment forced his rebel father to surrender himself to the Syrian regime in exchange for his son’s release.

According to Um Sha’aban: “Until today, Youssef still lives in a state of fear, isolation, anxiety and difficult sleeping as a result of the violence he witnessed, in addition to his feeling of guilt for the arrest of his father – not to mention our displacement from our hometown towards North Syria.”

On this point, Laila remarks: “When they [the children] are interrogated, they can offer information that harms other people, and so they blame themselves and feel a strong sense of guilt. In such cases, the child must be referred to a psychiatrist or expert social worker to help them.”

On the prospects of criminal accountability

When questioned on whether it is likely for the criminals complicit in the abuse of children to be held to account, Mishal Shamas refers to the 1989 Convention on the Right of the Child ratified by Syria, which forbade the torture, ill-treatment and harsh, inhumane and degrading punishment of children. All parties to the Convention pledged to respect the bases of International Law applicable to armed conflicts and relating to children.

Ultimately, despite the many obstacles which Syrians today face in the way of attaining justice and accountability, Shamas affirms the continued paramount importance for Syrian human rights groups to “intensify their efforts and continue to pursue the perpetrators of war crimes, torture and crimes against humanity in Syria, in accordance with the international judicial jurisdiction which is currently available in four European countries: namely Germany, Sweden, Austria and Norway.”

Shamas concludes: “This jurisdiction obligates the member states which are parties to international treaties to hold the perpetrators of such abuses accountable – even if those who violated the terms of those agreements were not on its territory – for perpetrating war crimes as per the Geneva conventions and conventional law. It is the right of those children to see the perpetrators brought to justice, and to obtain a suitable compensation for the crimes committed against them, as well as guarantees that such crimes would not be repeated in the future.”

This Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ) investigation was conducted in cooperation with and Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) – and with support from Free Press Unlimited. Published on Raseef22