By Nisreen Aladdin and Mukhtar al-Ibrahim

Damascus, Syria, (Al-Hayat) – Damascus: Reported

This investigation began during a bus ride from Damascus to it’s suburbs on Nov. 12, 2015. The reporter accidentally stumbled on the problem of unregistered children in Syria. Born during the ongoing war, these children were separated from their fathers who were kidnapped, killed or forced entirely to leave the country. As a result, they have been unavailable and incapable of registering their children as their own.

Travelling on a small white bus that was transporting civilians across military checkpoints, the vehicle was stopped by a government soldier for inspection. Pacing up and down the aisles, he requested and received identification papers. On the bus was a young woman looking nervously at the soldier, as she cradled a young baby in her arms. She stared at him, as if waiting for him to ask who the child belonged to.

But the child was not noticed. The soldier quickly left the bus and waved it on. As the bus moved on, the baby woke up and began crying, despite the mother’s attempts to calm it.

“What is her name?”

“She doesn’t have one registered yet,” the mother responded “And every so often I change my mind!”

This is the first time that the mother – called Rania – visited Damascus in five years, even though she lived only fourteen kilometres south of the capital. She had to travel to Damascus to try and register her child in the judicial courts. Rania married at the age of fifteen – a year and a half ago at time of meeting – to a man called Khalil Jumah who was displaced from another region in Syria. A local sheik married them in a ceremony with two witnesses present, as is customary outside the urbanized areas of Syria.

However , they did not receive the certification needed to register with the civil authorities.

Tragedy struck soon afterwards when their town was bombed in mid-2014. Rania was forced to flee to another town..

“Two months after that, my husband was killed. And later, my daughter was born without a marriage certificate.”

A week after our first meeting, Rania found herself confronting legal complications that would require a lawyer. This was because the Civil Registry had refused to register her daughter because the marriage contract was not available..

Her lawyer requested that she provide two witnesses from her hometown or paperwork to authenticate the marriage. This was very difficult because both witnesses had either fled the country or died in the war, while Rania only knew that her husband’s hometown is under the control of rebels.. This added an extra wrinkle, as it was unlikely government officials would recognize an official’s ruling from such an area.

Her lawyer requested 100,000 Syrian pounds (nearly $ 400) to mount the lawsuit on her behalf, but Rania could not afford the cost, especially not after the death of her husband and both her parents as well as the loss of all her property.

The Syrian civil code stipulates in Legislative Decree No. 26 of 2007, Chapter IV Article 28, paragraph c: (in case of children born to unregistered marriages, they cannot be registered until the marriage itself is registered).

For up to a full year, Rania was still at the judicial courts trying to register her daughter, until her debts caught up to her. Now she survives on the charity and kindness of others.

Rana’s case is one of many such stories emerging from the war in Syria, six years after the initial conflict began. This investigation was able to prove 29 different cases like Rania’s, after interviewing families in centres for displaced families in both Damascus and its countryside and in rural villages of the Quneitra Governate.

All cases investigated were of mothers suffering difficulties in registering the births of their children, for reasons related to Syria’s personal status laws, which requires the meeting of many conditions, an impossible mission in times of war, displacement and migration.

Among the conditions are the official registration of marriages that are needed to have one’s children recognized, that there is a documented marriage certificate for the husband with all his personal information, including date of birth, national number, parentage, etc… as expected of the wife, along with the wife’s guardian and the two adult male witnesses. Permission for marriage for the husband must also be granted from the military recruitment board, due to Syria’s national conscription laws. In addition, the address of the official certifying the marriage must be provided, along with the details for both the pre-marital dowry and the post-divorce support payments and the day of the wedding itself.

The situation is complicated in areas that fall outside the official authority, where identification issued by the opposition and the courts and local councils do not get any international recognition, let alone that of the Syrian government in Damascus.

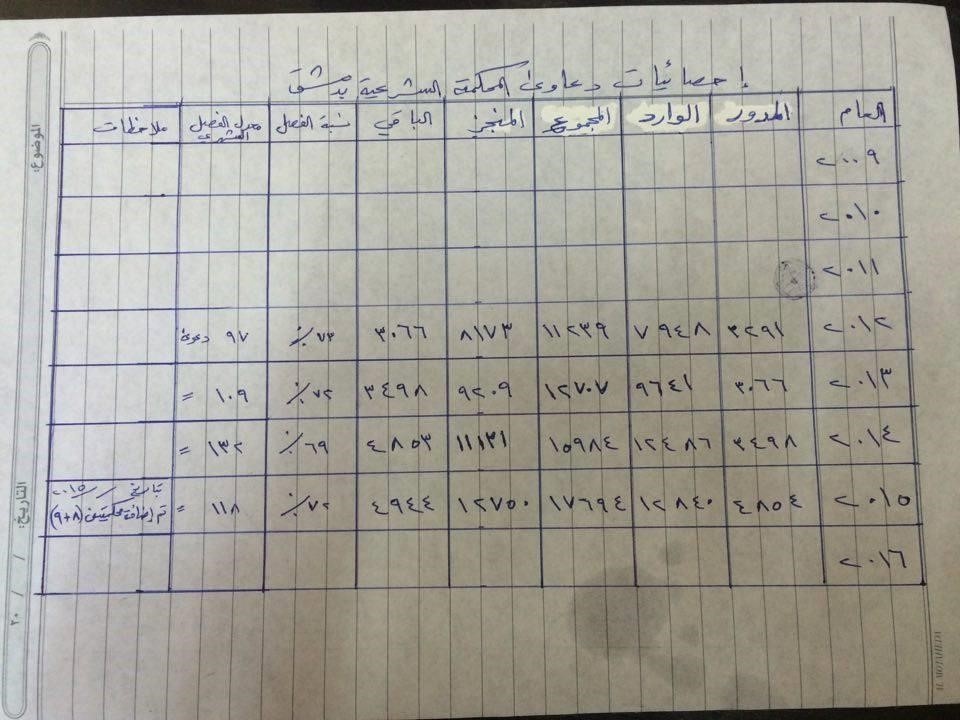

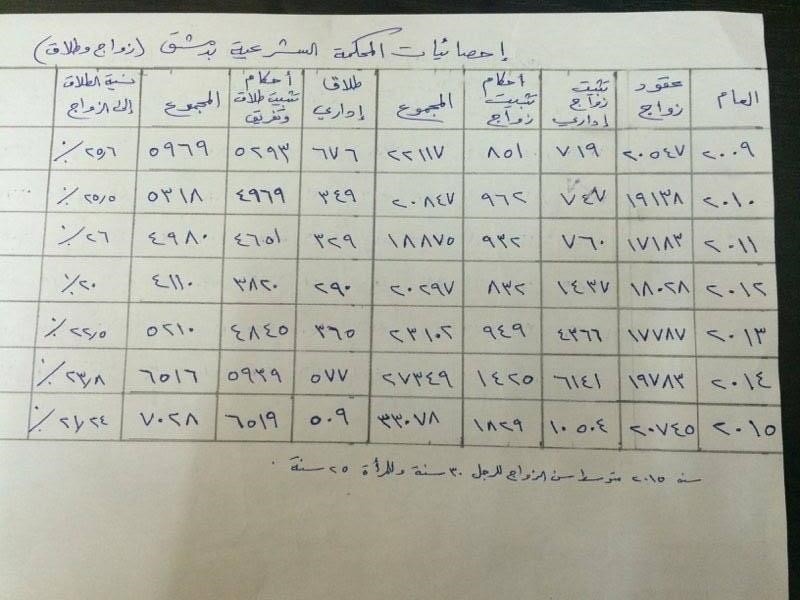

This is what leads to the accumulation of cases brought before the courts, for mothers like Rania trying to prove their children’s parentage in the absence of their husbands. According to the first Sharia judge in Damascus, who documents the personal status lawsuits records, the marriage and paternity claims rose more than tenfold in Syria, when comparing from the two years of pre-war to 2015.

This was further proven in interviews with around sixty family rights lawyers working in Damascus and around Quneitra, who collectively said that paternity claims have grown to be 80% of all their filed cases in the past five years, compared to less than 9% before the war.

Exacerbating the situation is the harsh approach by the Ministry of Justice towards marriage and paternity claims and paperwork expectations. According to judge Mahmoud Al-Maarawi, many women are also unable to afford the legal costs and fees which begin at $ 100.

Yousif Ayed Amaara, the president for the UN’s Family Reconciliation Office, is afraid for the murky future that awaits many of Syria’s young children, who he described as “victims of both the laws and the war”. He went on to say that these cases are constantly increasing, adding that “From 2007 to 2009 we had one such case, but now we are facing tens of new instances each month”.

I Want My Rights

A report issued by the Syrian Center for Policy Research entitled “Facing Fragmentation” states that Syrian families are being dispersed at a dangerous rate, with six million Syrians displaced within Syria itself and another four million having fled outside the country.

The 25-year-old Rola – better known as Um Salah – is one of the millions who have been displaced many times over in the country. She lives in a shelter for refugees in Latakia, where she arrived six months ago with her two children without any identification papers. Her husband disappeared three years ago after leaving home to go buy bread.

Um Salah did not have the family papers, and has been unable to enter her son at school. She has also been unable to receive aid, because her children are not registered in official records. However, children born of adultery were able to register, a fact that still resonates with her after her lawyer informed her.

| The Syrian civil code stipulates in Legislative Decree No. 26 of 2007, Chapter IV Article 28, paragraph c: (in case of children born to unregistered marriages, they cannot be registered until the marriage itself is registered). |

“I am not a prostitute, and I will not be and I will never be. But am I not harming my children? I brought them into this life and I have not provided them with their basic rights”.

Her father married her to a man who came to their village in 2011. She gave birth to their firstborn child Salah, without registering their marriage because of the volatility of the situation at the time. After less than a year of their marriage, they began a series of displacements because of the escalation of violence. She then gave birth to her second son Mohammad in 2012, and then lost her husband in 2013.

Rola’s husband is one of 65,000 people who have disappeared between March 2011 and August 2015, according to a report issued by Amnesty International. Meanwhile, the number of abductees in Syria have reached 20,000 between 2011 and the publication of this investigation according to Minister of State for the Syrian National Reconciliation Ali Haidar.

Rola stayed in the area close to the place of her husband’s disappearance, hoping he would come back and find her with their children. She was left with nothing but her wedding ring after she was forced to sell her jewelry to spend on her family before going on to the charity of others. She moved to Aleppo in 2014 and then to Latakia in 2015 in search of safety, after her son Salah was injured in his foot.

It came as a shock to her when she was asked for her children’s identification papers, and she forced to say they had been lost. She was subsequently given a room to share with another family, and upon requesting a separate room for her children she was asked to provide proof the children were hers or be at the risk dismissal from the shelter.

“I do not have any papers to prove my marriage and my children. According to government records I am still single.”

In surveying sixty lawyers in and around Damascus and Quneitra regarding the rise in parental suits during the war, answers varied between 80%, 100% and 700%. The survey also showed that by and large the largest obstacle was the absence of the husband.

| Civil status, No. 26 of Legislative Decree 2007 provides in paragraph (c): “No registration changes of any civil status to citizens inside or outside the country will be recognized unless under documents duly certified.” In article “28” in paragraph “b”: (b) “If the baby is illegal do not mention the name of the father or mother or both together in the birth records unless at the explicit request of them or by judicial order, and the Secretary of the Civil Registry will choose a first name and a surname unrelated to either parent.” |

Gone and never returned

Dunia listens carefully to every word her lawyer says.

The road to proving her marriage began again after the first attempt – a three month ordeal which culminated her leaving her previous lawyer as he attempted to take advantage of her circumstances and propositioned her.

Dunia married at the age of nineteen to a young man from the north of Syria who had come to work in Damascus and knows her husband’s surname, and his hometown. He had left her on Sept. 7, 2012 to go to work in Saqba, kissing her goodbye at five months pregnant. Three years have passed since he left, and since then, Dunia has rejected a proposal from a neighbor.

When she attempted to register her two year old daughter, she was surprised to learn that she needed to appoint a lawyer to overseer the procedure. Her landlord offered to pay her legal fees and after five sessions with the lawyer in his office, he asked for her to come without her landlord. When she arrived, she was propositioned and told that he would continue the legal suit for free and give her the money her landlord paid in exchange for a sexual relationship.

“I hit him with an ashtray and then I ran away and cried, all the while he was shouting at me, saying that he would send me to jail.”

Justice Adds Insult To Injury

Mahmoud Al-Maarawi claims that the Syrian crisis has imposed an incredible strain on the country’s judiciary, and that it has become essential to establish a competent judicial commission to maintain the rights of unregistered children and wives.

“Unfortunately, we are seeing a tightening of regulations from the Ministry of Justice, which is requesting a birth certificate from exclusively government hospitals, even though many women still deliver their babies with midwives or doctors in private clinics or even in their own homes. At the same time there are simply not enough judges with the courage to make rulings on these cases as the Ministry hands out more instructions”.

The Loss of Identification

It does not escape an observer that violence in Syria effected government buildings after 2011, where documents, files and records of births, bonds, divorces and marriages are believed lost. Afterwards, regional militias and opposition groups created their own records and civil registries as part of normalizing control over their territories.

A survey conducted by the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Syria in 2015 found that a lack or loss of personal documents, constituted a major challenge. According to the report, the personal status law in its current form is unable to help women to certify their marriages and their children, according to 81% of the respondents.

According to lawyers we met as they worked with their clients, the best-case paternity suits that take between three and five months are those when women presented the consent of their husbands or the husbands were able to appear before the courts with documentation to prove their paternity. Other “best case scenarios” are when the women have paperwork certifying the marriage and witnesses, as well as the possibility of communicating with either the husband or the witnesses or where the judge is convinced in the validity of the marriage, regardless of certification or proof.

If none of these instances are the case, the women are likely to lose cases or continue on for two years before losing, ultimately ending in a dismissal of the case and the lack of registration of children in most cases.

The Bosnian and Tunisian Experiences As a Solution?

A 1998 law in Tunis related to children with unknown parentage gave Tunisian mothers the possibility to identify their children as their own, without a father present. This would be predicated on proving the children were their own (through shared DNA, witnesses, etc…) but would provide the children born out of wedlock all the legal rights available to those born in a recognized marriage.

But this cannot be applied directly in Syria due to the personal status law in the country, which is derived from Islamic Sharia, and is incompatible with Tunisian laws.

Meanwhile in Bosnia, the country suffered a long war in the 90’s. Families were dispersed and many were raped. This caused many parentage problems that culminated in the adoption of an old Yugoslav law which did not put concern on whether the children were legitimate or not. This allowed single mothers to register their children even if the father is unknown and receive full rights. This was a solution to a problem women and children suffered during the Bosnian war along with its systematic rape and forced pregnancy without a father.

A Typical Marriage Contract

Activists and lawyers are calling for a basic, pre-approved written marriage contract that would only need the particulars of each marriage agreement filled in. This would be accepted without fault by the judges, and would contain the evidence supporting the couple and the witnesses present, notarize the wife’s signature as consent, provide fingerprints of her husband and outline what guarantees are available to the women in case of their husband’s death, disappearance or migration. This would be temporary until the government takes control over the entirety of the country and the Sharia courts would be reinstated nationally.

The lawyers who were consulted in this investigation regarding the personal status law said that it did not help Syrian women to prove the validity of their marriages, especially not when their husbands had disappeared or if they had lost their marital documents.

They suggested to found a civil records commission specializing in dealing with children born during the war with records of their mothers until the identification of their fathers takes place when the war ends. This is to preserve the rights of the children, so as not to be constrained or considered stateless and to take the same treatment as with abandoned children. This would be in the hope of reaching a solution for those unrecognized, especially the cases of these mothers who are stuck between divorce or widowhood as well as their fatherless children.

This investigation was completed with the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) – www.arij.net and coached by Hamoud Almahmoud. Nicolas Awwad translated the investigation into English.