By means of official documents, exclusive testimonies and field research, this investigation traces how chemical warehouses and pharmaceutical companies exploited drug licensing systems to import diphenhydramine into Syria and make it the key ingredient in the manufacture of counterfeit Captagon tablets.

Our investigation exposes the extent of an international network fuelling a multi-billion-dollar drug industry stretching from the port of Nhava Sheva in India, via Beirut, to a mysterious, long fortified mansion in the Damascus Suburb. The whole network was masterminded by the Assad’s regime Syrian army’s Fourth Division, under the command of Maher al-Assad, using official pharmaceutical cover.

Businessman and former MP Amer Tayseer Kheiti took over an old potato chip factory in the city of Douma, in the Damascus suburbs, and turned it into a well-guarded drug production facility under the supervision of the Fourth Division.

The chemicals found in the Captagon factories had come from India, China, Germany, and Britain.

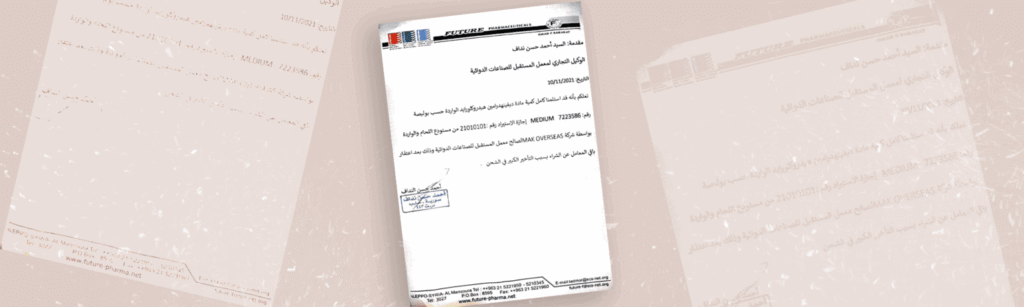

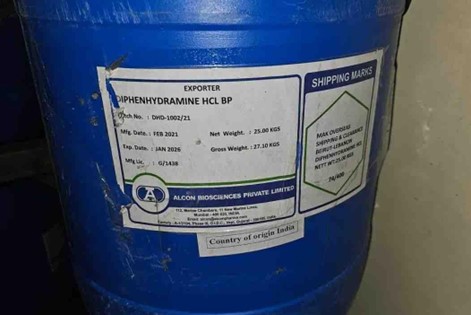

In 2021, Indian authorities recorded the export to Syria of 400 drums of diphenhydramine, a pharmaceutical compound used as an antihistamine. The listed recipient for the shipment was a company called Future Pharmaceuticals. The point of arrival was given as Beirut port, from where it was transported by road to the Damascus suburb. There, the shipment arrived at the warehouse of the official Syrian importer: the chemical company Eyad Laham and Partner, based in the Damascus suburb.

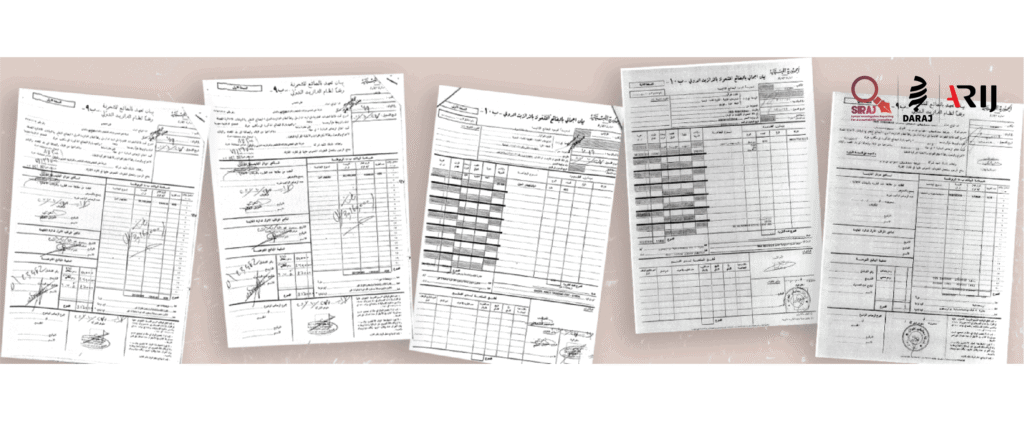

All the official documents were there: approvals from the ministries of health, economy and customs, and a shipping route that appeared legal and gave no grounds for suspicion.

But behind this bureaucratic façade, a completely different operation had been put together by people involved in the Captagon industry.

On December 8 2024, these same drums of diphenhydramine came to light at a secret Captagon making facility housed in a mansion on the outskirts of Damascus that was under the control of the Syrian army’s Fourth Division, commanded by Maher al-Assad, brother of former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. This plant was not licensed, and the fact that the drums were there was no coincidence.

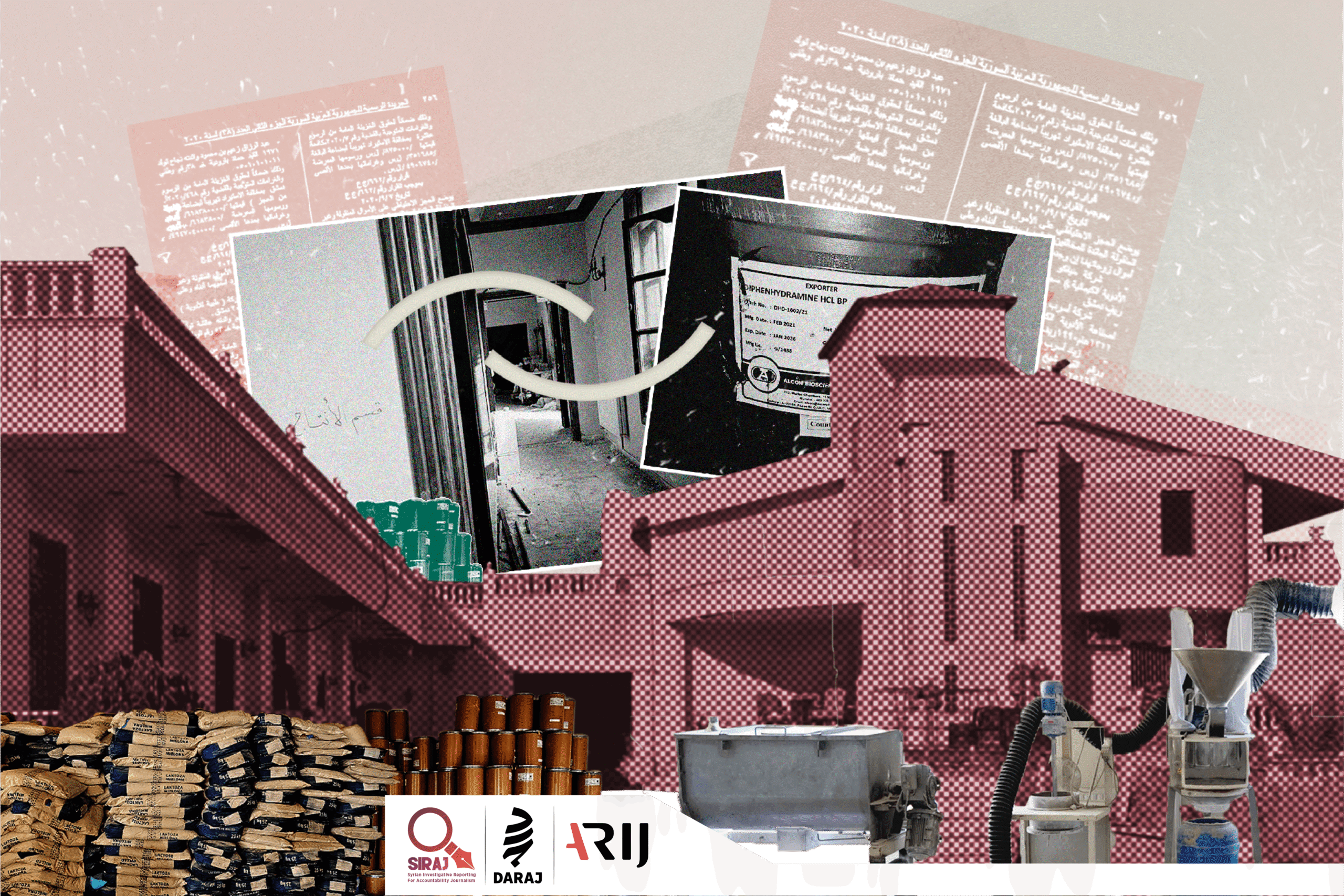

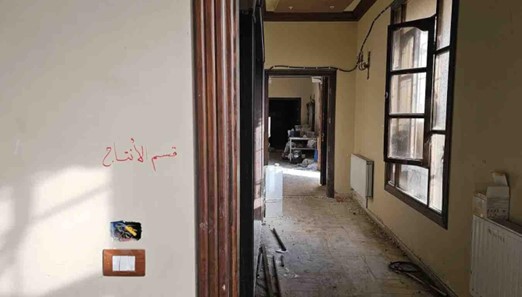

Photos from inside one of the Captagon production factories, which the investigation team visited

That day brought to light a hidden network that had been quietly operating for more than a decade, protected by the walls of a mansion shrouded in secrecy for 13 years.

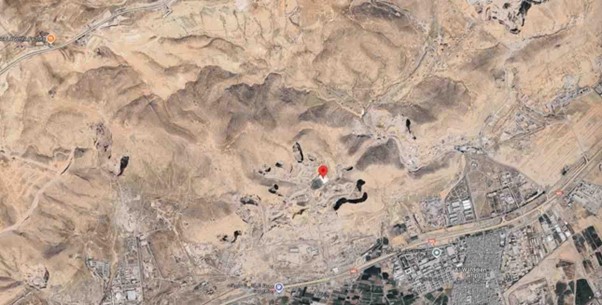

The mansion sits between the towns of Yafour and Dimmas in a strategic area west of Damascus, on the international highway between Beirut, Damascus and the Damascus suburb area, and had for years been the preserve of the Fourth Division.

With the end of the Assad family’s rule in Syria, local people were finally able to see behind the gilded iron gates and marble walls of this mansion and discover its secrets.

We are now inside Syria’s largest Captagon factory

This investigation charts the global supply chains that fuelled the Captagon industry in Syria, which had one of the fastest-growing synthetic drug economies in the world. Captagon, a powerful amphetamine, not only drove a regional addiction crisis, but also became a financial lifeline for sanctioned elements of the Assad regime, for the Lebanese Hezbollah militia, and for their networks across the Levant.

A study by the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR) shows that Syria became a global hub for the production of Captagon and reached an unprecedented level of sophistication in drug manufacture during the Assad regime, thanks to its large-scale production and export of Captagon. The value of the Captagon trade outstripped the country’s legal exports many times over, making it an economic lifeline for the former Syrian regime and its allies.

The Captagon Room

Walking past piles of bags and hundreds of drums filled with various raw materials, ARIJ’s investigation team – working alongside journalists from the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism Association (Siraj) – was able to examine the contents of one of the palace’s spacious ground floor rooms. They found black bags and large blue and black containers which were stamped with numbers, barcodes and coding strings, which made it possible to track them from their country of origin to the final importer.

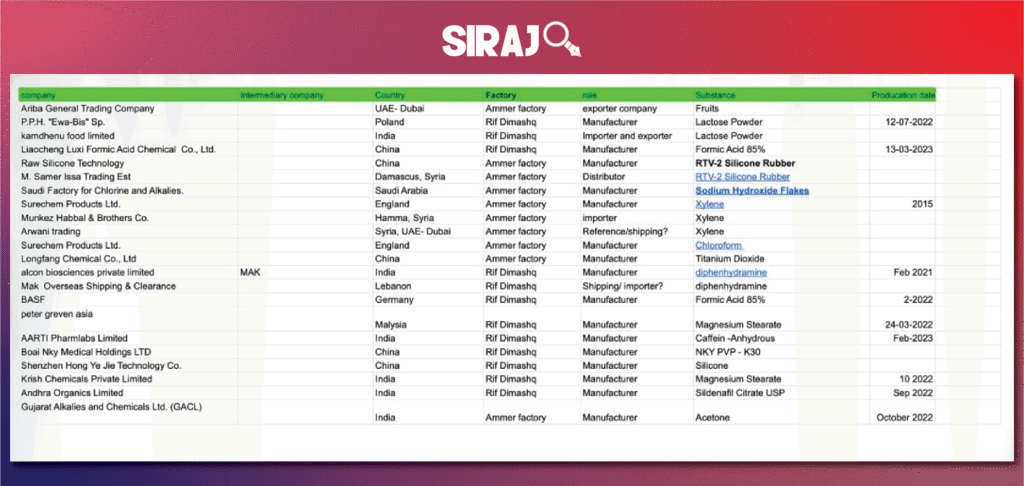

An image from the database documenting the raw materials found inside the Captagon factories belonging to the Fourth Division in Damascus.

We established that ten essential chemicals had been imported from factories in China, India, Malaysia, Germany, Poland, and the United Kingdom. One particular shipment contained diphenhydramine. This is a substance used in making counterfeit Captagon tablets, many of which have been seized in Europe.

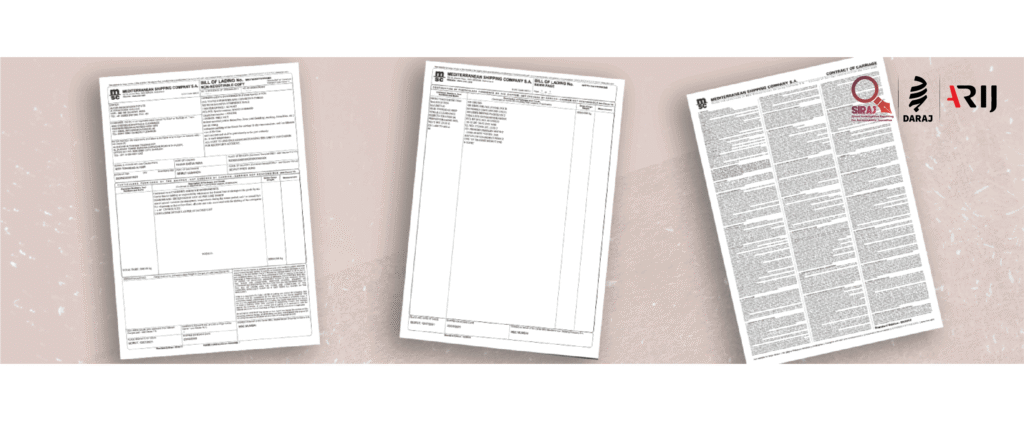

A shipment of drugs, labelled as “perfumes and cosmetics” in the shipping document, was sent from a pharmaceutical factory in the Indian state of Gujarat to a Lebanese company in the western Bekaa. This document, bearing the signature of the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) – one of the world’s largest shipping companies, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland – appears normal. It shows the name of the shipper, the recipient, and the contents of the container, listed as “cosmetics”.

The Lebanese company involved was the local branch of the Syrian-owned Mak Overseas Shipping & Clearance. It is based in the town of Al-Rafid, near the Lebanon-Syria border, and owned by a Lebanese national and two Syrian partners.

What the details of the shipping documents fail to mention is that the main ingredient of the consignment (diphenhydramine) is one of the components used in the manufacture of Captagon tablets. When it arrived in Lebanon, the shipment did not go to a shop or perfume factory, but was instead sent on to Syria. There, secret workshops controlled by the Fourth Division in areas like Douma have been actively producing hundreds of thousands of tablets for export to the Gulf and Europe.

From database searches and contacts with the Lebanese authorities, we found that this shipment had transited through Lebanon to Syria under an import licence from the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade – and with the approval of the Environment Directorate in Damascus Suburb, and the former minister of economy – for use in the manufacture of medicines.

According to documents obtained by our team of investigators, the material was shipped by Mak Overseas from the Alcon Biosciences plant in India via the port of Nhava Sheva to the Logistic Free Zone Beirut port. It was then transported by land to Tripoli and from there to Jdeidet Yabous in the Damascus Suburb.

After the consignment entered Syria, it was stored in a warehouse belonging to chemical company Eyad Laham and Partner in Jdeidet Artouz in the Damascus Suburb area, before being sold on to Future Pharmaceuticals in Aleppo, according to the import licence No. 21020101.

A recurring pattern of financial irregularities and smuggling

Shipping documents list 400 barrels of diphenhydramine with a total weight of ten tonnes and a value of US$20,000 along with official approvals for their use in the manufacture of medicines.

Shipping and receipt of the shipment

Receipt from Future Pharmaceuticals

It is important to note that the owner of Future Pharmaceuticals, Omar Farouk Barakat, has a criminal record for smuggling, according to an official decision issued by the Syrian Ministry of Finance.

Official records show a long history of financial and legal violations linked to Barakat and his company. On December 16 2014, his movable and immovable assets were provisionally impounded under case No. 21/2014 of the Third Anti-Narcotics Unit, for smuggling imported goods worth 78,453,500 Syrian pounds. He faced a maximum fine of 627,628,000 Syrian pounds. This seizure of assets was temporarily lifted on May 17 2015, after the legal grounds for it lapsed.

However, on 4 February 2016, a new financial seizure was imposed on the Future Pharmaceuticals plant in Kafr Dael-Mansoura and its legal representative Omar Barakat, under case No. 4/2015. This covered smuggling of imported goods not exempt from seizure with a value of 20,510,637 Syrian pounds, a charge carrying a maximum fine of 102,553,185 Syrian pounds.

On September 7 2020, a third seizure of assets was ordered on Barakat and on any assets held by his wife, under case No. 42/2020 run by the same authority (Third Anti-Narcotics Unit). This time the charge was illicit import and export of goods exempt from seizure (translator’s note: should be not exempt?), worth 502,856,725 Syrian pounds, which carried a maximum fine of 3,787,493,300 Syrian pounds.

Finally, Omar Farouk Barakat’s name reappears in the Syrian Official Gazette on July 25 2024, in connection with another financial seizure. This all reflects a clear pattern of repeated violations and links to cases of smuggling and tax evasion over at least ten years.

Despite this track record, Barakat’s Future Pharmaceuticals plant obtained the necessary approval to import large quantities of diphenhydramine under official import licence no. 210201014715. We found some of this substance at a Captagon manufacturing facility, allegedly controlled by the Fourth Division.

Syrian Official Gazette entry on seizure of assets from the owner of the Future Pharmaceuticals plant.

Our investigation team consulted three pharmaceutical industry experts – two pharmacists and a drug factory production manager – and shared with them details of the shipment the roughly 400 drums (around ten tonnes) of diphenhydramine, imported by the Future Pharmaceutical factory in Syria.

All three experts agreed that the quantity of diphenhydramine imported had “no pharmaceutical justification” and was inappropriate for the needs of any licensed drug factory, even if the substance was used across a variety of treatments, such as creams, syrups and tablets.

Aya Al-Oran, a pharmacist with a master’s degree in pharmaceutical technology from Anadolu University in Turkey, explains that this amount of imported diphenhydramine (about ten tonnes of raw material) was so large that it would be difficult to justify for any pharmaceutical use.

According to Al-Oran, the amount of diphenhydramine was enough to produce in theory around ten million boxes of medicine at the maximum dose (50 milligrams), or up to 25 million boxes at the less common 12.5 milligram dose. She adds: “To handle such huge quantities would need a plant with a production capacity of around 7,000 boxes, which is way more than most local drug factories could manage, without a large distribution or export network.”

“The limited shelf life of the active ingredient, especially when it’s in a highly perishable form like syrup, means it may need to be used within just two years. This reinforces the hypothesis that these large quantities were intended for some purpose other than normal medicinal use,” says Al-Oran.

Arafat Tayawi, production manager at a drug factory in Hama province, agrees that it is impossible that any licensed factory would need such quantities for purely medicinal use.

Ayman Khosraf is a pharmacist specialising in laboratory diagnostics and a researcher in biotechnology at Gaziantep University in Turkey. He says that 400 drums (ten tonnes) of imported diphenhydramine is far in excess of what any normal medicinal drug laboratory would need.

He goes on to explain, however, that that the economic and security environment within which the pharmaceutical industry in Syria operated during the war years made it difficult for local companies to completely ensure the tracking of shipments or to control their end use.

“The prevailing security environment forced many drug firms to yield to powerful networks, either through direct pressure or the use of front companies that were given licenses to import materials which were then diverted into making narcotics. In such an environment, the license holder is not always the real decision maker,” says Khosraf.

A former worker at a Captagon manufacturing plant in Damascus revealed exclusively to our investigation team that the essential chemicals would arrive in Lebanon with legal commercial documents that classified them as cosmetics, food supplements or medicines. Then they would be taken across the border to secret production facilities run by people close to the Assad family.

“No one asked any questions,” he says. “The paperwork was all in order, and the shipments went through as if they were for making ordinary medicines. It wasn’t just a one-off. This was an organised system designed to keep the vital supply chains running for making Captagon, despite the international sanctions that the Assad regime and its institutions linked to chemical production were under at the time.”

In the spring of 2024, a World Bank report estimated that the Captagon market in Syria was worth between $1.9 billion and $5.6 billion a year, not far short of Syria’s total GDP for 2023. The report stated that “entities linked to Syria” had profited from the various stages of the Captagon trade, from production to distribution. It estimated annual revenues at between $0.6 billion and $1.9 billion.

In its response to questions from our investigation team, the interior ministry of the current Syrian government said that “those who ran the narcotics networks in Syria were the leading figures in Assad’s regime and worked under his direct supervision.” The ministry said that some of those involved had fled after the fall of the regime, while the rest were being tracked down inside the country.

Inside the mansion, a production line had been set up amid the scattered drums labelled as containing diphenhydramine. Dozens more such drums, all of them from the same Indian factory, were to be found in the warehouse,.

The production section in the mansion used to make Captagon tablets – exclusive

It was somewhat surprising to find diphenhydramine in a plant making Captagon, since this substance has a sedative effect, causing drowsiness and possibly dizziness, dryness of the mouth and eyes, blurred vision and raised heart rate.

According to Dr Nicola Lee, a researcher at the National Drug Research Institute at Curtin University in the US (translator’s note: Curtin University’s NDRI is located in Perth, Australia, not the US) diphenhydramine has an opposite effect to that of the stimulant Captagon. She adds that the manufacture of fake Captagon is not well regulated, making it even more dangerous.

The use of diphenhydramine in the manufacture of fake Captagon from Syria came as no surprise, however, to other researchers and law enforcement authorities. The US Centre for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) points out that this and other materials go into making counterfeit Captagon, according to research conducted in collaboration with the Forensic Laboratories Department of the Public Security Directorate in the Jordanian capital, Amman.

According to the CFSRE, mixing together sedatives and stimulants does not cancel out their effects, but instead brings about a state of complex agitation in the user. It engenders a feeling of excitement and euphoria but also slow or confused thinking, impaired decision-making and increased impulsive behaviour.

Diphenhydramine was used in the manufacture of a consignment of counterfeit Captagon tablets from Syria seized in Romania in 2020. The German authorities also reported that diphenhydramine was found in some consignments of Captagon, according to a report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction in 2023.

Laurent Laniel, a researcher on crime and drugs at the European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA), says that forensic analysis of seized Captagon tablets carried out by several EU countries revealed the presence of diphenhydramine in many of the samples. The main active ingredient detected, however, was amphetamine.

Being an illegal substance, amphetamine is expensive to make or purchase from illegal sources, Laniel adds. That is why cheaper and more readily available substances – like caffeine, theophylline and diphenhydramine – are often used in the manufacture of Captagon tablets.

From India to Beirut

About a year after the Captagon seizure in Romania, a consignment of diphenhydramine arrived at Beirut port from India.

According to the labels on the drums, the Indian company Alcon Biosciences Private Limited, which manufactured the diphenhydramine in early 2021, shipped 400 drums of it through Beirut port to a company called Mak Overseas Shipping & Clearance.

One of the barrels of diphenhydramine found in the unlicensed factory

Caroline Rose, director of the Crime-Conflict Nexus and Military Withdrawals Portfolio at the New Lines Institute, says that China and India are main centres for the production of dual-use raw materials. These are chemicals that can be used to manufacture synthetic drugs, but which are not listed by the International Narcotics Control Board. This means they are not subject to any security or legal controls.

Rose adds that the lack of any legal restriction on the trade in dual-use raw materials, coupled with easy trading routes with China and India, may be offering Syrian Captagon producers a golden opportunity to continue their activities.

The Ministry of Interior states that “shipments of raw materials and equipment used in the manufacturing process would enter Syria illegally or be classified as pharmaceutical manufacturing machinery.” It explains that “organisations supplying the country with logistical materials are criminal organisations and networks, and we are coordinating with several other countries to dismantle them.”

Responding to questions from the investigation team, the Lebanese General Directorate of Customs said “it appears that a consignment of diphenhydramine entered through the free zone in the port of Beirut and was transited on to Syria, in accordance with legal procedures and official documents. It has been established that the Syrian importing company was duly licensed and had obtained an import permit for this consignment from the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Trade, with the approval of both the Directorate of Environment in the Damascus Suburb and the Minister of Economy for use in the manufacture of medicines.”

But, though the shipment was exported for legitimate purposes, many of the drums of diphenhydramine ended up in an illegal Captagon plant in the Damascus suburb, the same area where approvals for the imported shipment had been issued.

The company responsible for the shipping and logistics denied any knowledge of what had happened to the consignment. In a written response dated June 25 2025, Mak Overseas Shipping & Clearance wrote that its role was limited to providing “logistical services.” It said the shipment of diphenhydramine was sent to Syria “legally”, with official authorisation, including a licence issued by the Syrian Ministry of Health.

The company went on to say it delivered the drums “to a well-known pharmaceutical plant” in Damascus and that it was not responsible for what happened subsequently, emphasising that material was “not subject to control” and was not listed as a banned substance.

The company said it did not know how the shipment had ended up in a secret factory rumoured to be run by a company directly linked to the Fourth Division, commanded by the ex president’s brother, Maher al-Assad.

According to documents obtained by the investigation team, the consignment of diphenhydramine left the port of Beirut on October 25 2021, and passed through Tripoli to the Eyad Laham warehouse in the Damascus suburb, before being sent on to the Future Pharmaceutical factory in Aleppo.

Future Pharmaceuticals failed to answer our questions over whether it had taken delivery of the shipment of diphenhydramine or how dozens of drums from it had ended up in a mansion in the Damascus Suburb used for manufacturing Captagon.

We were unable to find any registered address for the Eyad Laham and Partner company in the Damascus Suburb. When we called the number given in the Lebanese customs clearance documents as that of the company receiving the shipment, it turned out that the number was that of the shipping company, Mak Overseas. The investigation team also contacted five pharmacies in the Jdeidet Artouz area, the most likely location for the company. But all of them said they had no knowledge of it and had never had dealings with it.

Transport via Lebanon

Caroline Rose, from the New Lines Institute, who has conducted extensive research into the Captagon trade in Syria, thinks that using Lebanese ports, like Beirut, to import raw materials for making Captagon is a way of averting suspicion, given the distrust surrounding those circles loyal to the former regime in Syria. She argues that transporting raw materials through Lebanon instead of exporting them directly to Syria may be an attempt to conceal the illegal production and trading of Captagon inside Syria and to maintain the fiction that Syria is merely a transit hub and not a manufacturing country.

A former production manager at a Syrian pharmaceutical company revealed that the raw materials used in the manufacture of Captagon, such as phenylacetone and phenylacetic acid, arrive in Lebanon in shipments from countries like Iran, China and India and are then driven into Syria. These materials are listed as ingredients for making pharmaceuticals or cleaning products, which makes it easier to take them across borders without arousing suspicion.

We found more information about how the ingredients used to make Captagon pass between Syria and Lebanon from the file the Lebanese Internal Security Forces have on Hassan Daqqou, the so-called “Captagon King” and others charged with trafficking and smuggling Captagon.

This case file, which runs to over 500 pages, shows that one of the accused had been smuggling chemicals used to make Captagon – like caffeine, lactose and paracetamol – between Syria and Lebanon since 2013.

Infographic here

Caption: Route of diphenhydramine shipment from India to Damascus suburb

The investigation file showed that the suspect also acted as an intermediary between Daqqou (who was living in Beirut) and customers in Syria who required oil for use in making Captagon.

The investigating authorities (the information division of the Internal Security Forces) also found a conversation on Hassan Daqqou’s phone in which he had asked one of the suspected drug traffickers and manufacturers to obtain some ephedrine, used in the manufacture of Captagon. In 2014, a deal was concluded to purchase eight sacks (large bags for carrying bulk materials like chemicals) of caustic soda and ammonium bicarbonate, both substances “suspected of being used in the manufacture of Captagon.” Daqqou, however, denied knowing anything about these phone messages.

Daqqou was reported as saying he has been part of the Syrian Fourth Division security team since 2014, and used to enter Syria from Lebanon in Hezbollah convoys.

Daqqou was put on the US sanctions list in 2023 for his involvement in “drug smuggling operations by the Syrian army’s Fourth Division, commanded by Maher al-Assad, under Hezbollah cover.”

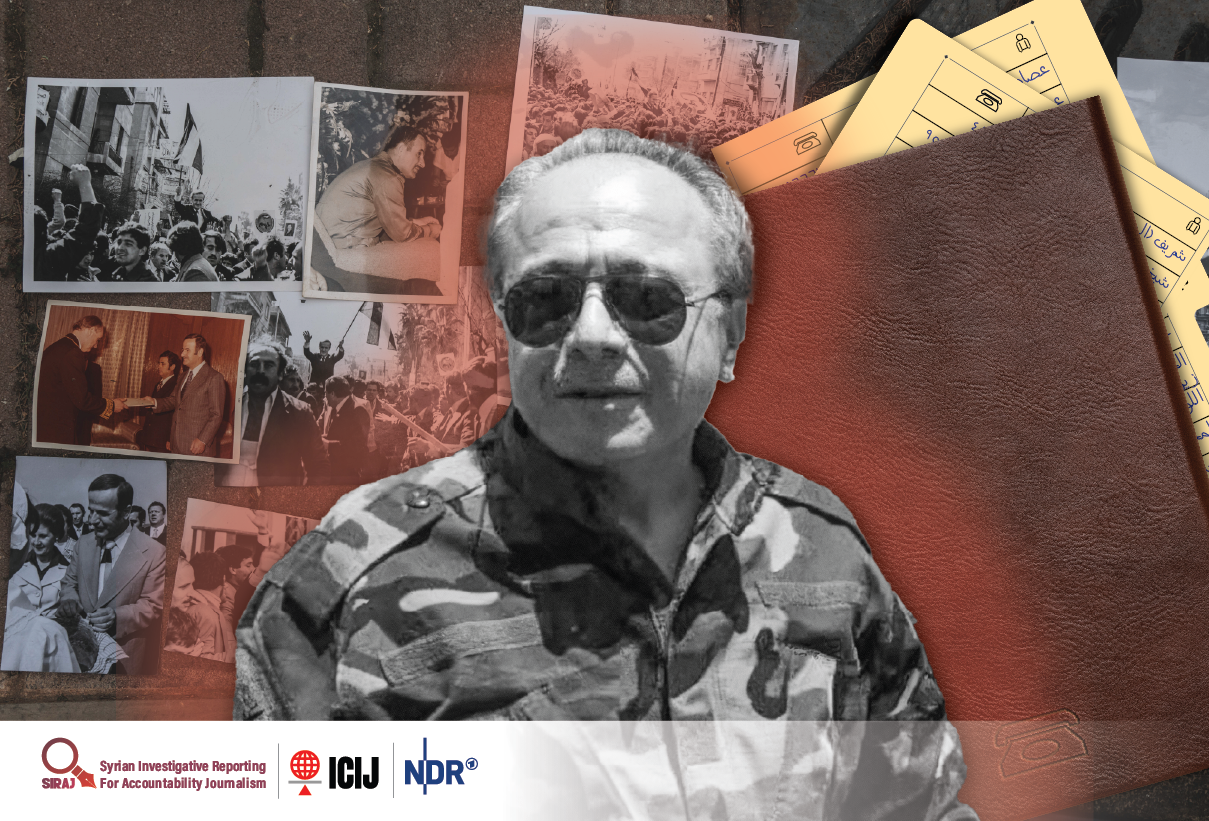

The Fourth Division and the Captagon industry

After the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in March 2011 ,and the Syrian regime’s violent response, the European Union imposed a range of sanctions on Syria covering 23 sectors.

Despite the ban on sale of products used in the oil, electricity and other sectors, which the former regime could have used in the violent clampdown on civilians, some of the raw materials used in the manufacture of Captagon remained exempt from sanctions. This was due in part to the fact that some of these materials are used also in the manufacture of pharmaceuticals.

A statement by the UK government in 2023, estimated that 80 per cent of the world’s Captagon was made in Syria. And independent experts have put the value of the Captagon trade in Syria at $57 billion.

In August 2011, the US issued Executive Order 13582, imposing sanctions on the former Syrian regime. By 2019, the US administration had enacted the Caesar Act, which imposes secondary sanctions on anyone proved to have knowingly provided significant support to the Syrian government.

The US administration set out to punish anyone involved in the Captagon industry, pointing out that proceeds from the “illicit Captagon trade have become a major source of income for the Assad regime, the Syrian armed forces, and paramilitary forces in Syria.”

The US Treasury Department repeatedly linked the Fourth Division to illicit trade, particularly that involving Captagon, saying: “Maher al-Assad and the Fourth Division are known to run numerous illicit revenue streams, ranging from cigarette and mobile phone smuggling, to facilitating the production and smuggling of Captagon.”

Syria’s interior ministry has revealed that its investigations have led to “the seizure of over ten major factories and smaller workshops since the fall of the regime” and that they were “mostly located in areas controlled by the Fourth Division.”

The factory in the Damascus Suburb and the Fourth Division

After the fall of the Assad regime, video clips circulated on social media showing people from villages along the Damascus and Lebanon highway entering the mansion where we found the shipment of diphenhydramine. There they found rooms crammed with drums, large sacks and thick plastic bags filled with bulk raw materials as well as scales and mixers, while out in the courtyard were forklifts and packing machines.

Those posting the videos linked the factory to Maher al-Assad’s Fourth Division.

Mohammed Arsali, who lives in the Dimmas area in the Damascus Suburb, says the mansion was controlled by Fourth Division’s security office, headed by Bassim Fawzi Deeb, and that security barriers lined the main road leading to it.

Arsali goes on to say that, after discovering what had gone on inside the mansion, they summoned a local dignitary, who decided to burn the drugs, while the contents of the factory remained under heavy guard.

Another local resident, Shadi Sohoud, said that the whole area up to three kilometres around the mansion was full of luxury houses, owned by Syrians and other nationalities. He said that, from 2012, the security forces of the former regime had controlled the area, while the road to it had been under tight security from the Fourth Division.

Arsali reports that trucks would drive to and from the luxury house along the road to this area without local people knowing what they were carrying.

Testimony from local residents also indicates that huge trucks had used this road for years without anyone knowing what was inside them. Several accounts confirm that Bassim Fawzi Deeb, who was a major in Dimmas before being promoted to colonel, subsequently took charge of the security office adjacent to the mansion. Witness said that no truck could enter or move except on his direct orders.

In response to our questions, the Syrian Ministry of Interior said that “most of the major Captagon manufacturing plants seized after the fall of the regime came under the Fourth Division and were concentrated in border areas and along the Syrian coast.”

A soap factory… brainwashing

Our investigation team documented the presence of raw materials used in the manufacture of counterfeit Captagon in another factory, on a hill overlooking a main road west of Damascus, a place also under the control of the Fourth Division.

Inside vast, unlit warehouses on abandoned land in the city of Douma, our team spotted thousands of narcotics concealed inside pieces of furniture, artificial fruit, coloured gravel and even electrical voltage stabilisers. These impounded materials had been stacked on wooden pallets, ready to be loaded onto a truck outside.

The huge building, surrounded by high walls, had originally been a factory for producing potato crisps, but was later turned into a plant for making narcotics, well-fortified and under tight security.

After the fall of the Syrian regime, the factory was opened up to local residents for the first time in years. One of them, Abu Ahmad, a man in his sixties who recently returned to his land next to the factory, said: “We all knew this factory belonged to the Fourth Division and was under Maher al-Assad’s control. No one would dare go near it. We used to watch these lorries and huge refrigerated trucks carrying stuff at night. If they headed south, we knew they were on their way to Jordan or the Gulf, and if they went north, they were going towards the sea.”

The factory stands between two hills and can be seen at night from the centre of Douma. It was run by Amer Tayseer Kheiti, a well-known businessman and former member of the Syrian parliament, who was sanctioned by the US in 2020, over his ties to the Assad regime. The UK also imposed sanctions on him, because he owned multiple companies in Syria “which facilitate the production and smuggling of drugs, including Captagon.”

Known to be one of the financial fronts of the Fourth Division, Kheiti fled the country after the regime fell. He had set up the factory in 2017, employing both military personnel and pharmacists affiliated with the Fourth Division to run its production lines.

The factory site

Mohammed Fares al-Toot, the original owner of the factory, told the investigation team: “My brothers and I owned this place, as well as a number of plants specialising in food and canned goods. This was the biggest factory in Syria and maybe the whole Middle east for potato crisps.”

The plant was taken over in 2018, he said. “Amid all the chaos in Syria, Amer Tayseer Kheiti took over the factory. He was an agent for Maher al-Assad and Ghassan Bilal, of the Fourth Division.”

He said that it had been badly damaged: “There were more than 160 production lines at the plant … everything was looted, stolen.”

Our investigation team managed to gain entry to the site after the fall of the regime and found large quantities of chemicals, including chloroform, formaldehyde, hydrochloric acid, petroleum ether and ethyl acetate. They were stored in brown boxes bearing the logo of a major UK chemical company.

Inside the Captagon manufacturing plant in Douma – which had been under the control of the Fourth Division, commanded by Maher al-Assad – the team found boxes of xylene, a pure chemical usually used as a laboratory solvent and classified as harmful to health under European safety standards.

Xylene is sometimes used as a solvent in the manufacture of amphetamine, the main active ingredient in Captagon, particularly when it is made using irregular production lines relying on cheap, readily available chemicals.

The 2.5 litre containers found inside the laboratory carried the name of Surechem Products Ltd, a British company based in Suffolk, England. The labels on them showed the production batch number 16448/3a and an expiry date of November 2015.

Documents show that the shipment was imported into Syria to a company called Manqiz Habbal and Brothers, based on Al-Alamein Street in Hama, through a distributor called Arwani Trading.

In one of the rooms, we found hundreds of business cards in the name Amer Tayseer Kheiti, clearly showing that he had directly overseen the operations at the plant and its conversion into what residents called a “brainwashing factory.”

Abu Ahmad was not the only witness to what had been going on there. Another man from Douma, whose right leg showed signs of torture, broke in saying he had been detained by the Fourth Division: “Their men would come and go from the factory in black cars, some without licence plates. They stopped me going into the quarry next door and told me not to come back to that area. They did the same to many farmers.”

Lighting up a cigarette, he points to the hills behind, where the factory building is clearly visible: “They told us it was a soap making plant…but when it started up, we realised it was really a brainwashing factory.”

This investigation was carried out with the support of ARIJ.