Nour Ibrahim – Damascus

Many are aware of the fact that, inside Syria’s displaced persons’ camps, women are constantly subjected to sexual extortion. More obscure is what happens to their peers at the capital’s so-called shelters and those of the surrounding rural areas. Here, the identity of the perpetrator may vary, but the women’s lot of suffering and exploitation is just as gruesome. Whether in camps or government shelters, the “sex in return for food” deal is the order of the day.

Since 2012, 20 year-old Reem has been living with her family at the Kafr Sousa shelter in Damascus. For three consecutive months, she had been sexually assaulted by the shelter’s supervisor. Fearing defamation, she did not dare to whisper a word about it.

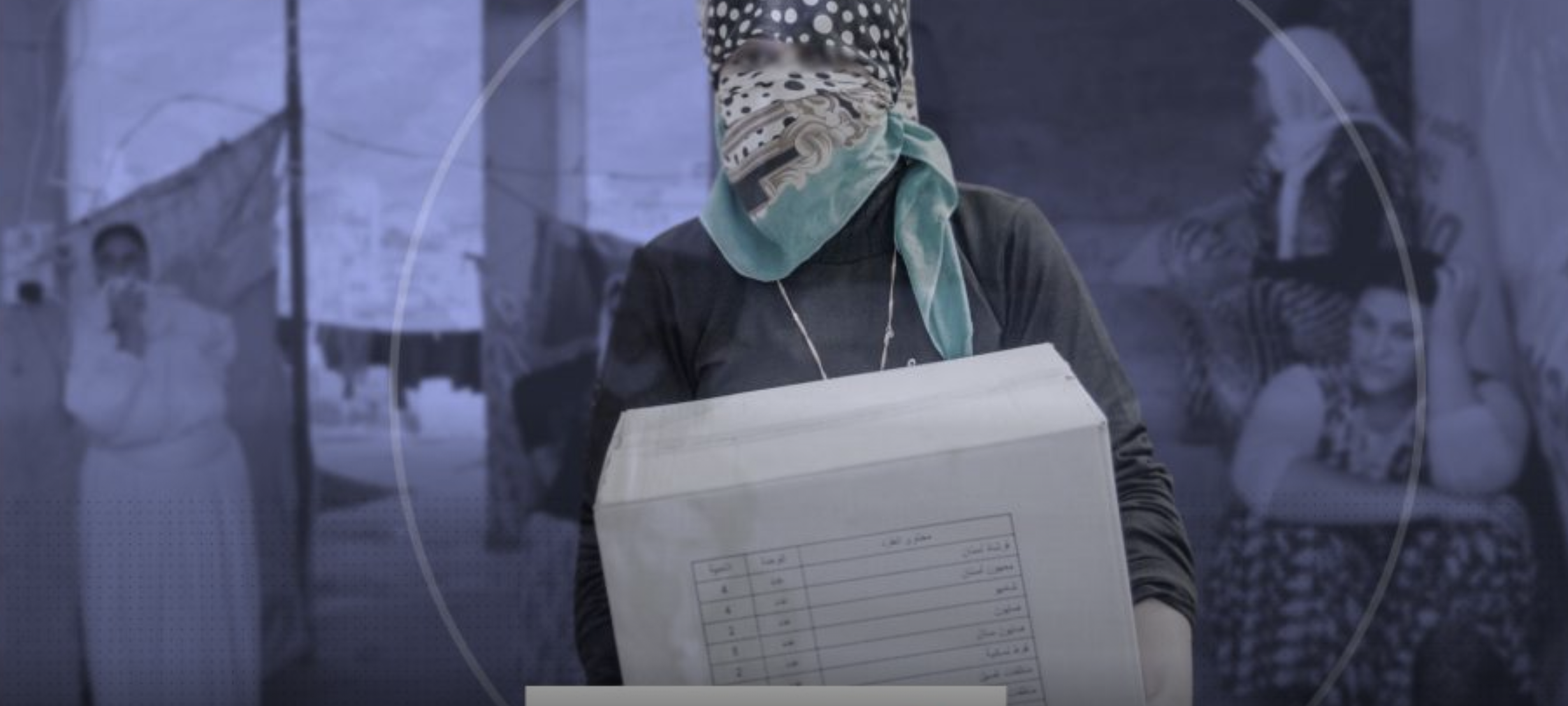

I met Reem outside her residence back in October of 2017. Terrified, she requested anonymity, both for the sake of her family’s safety and her own.

It had all started the year before when, one day, Reem’s mother sent her to collect the food ration. The family had been living off of this aid since they first moved into the shelter from rural Damascus. That day, the supervisor in charge of distribution forced the young girl to have sex with him in exchange for her family’s share. The abuse continued for a while. When Reem finally asked her assaulter to stop, he threatened to throw her family out, and tell everyone about what happened between them.

“I was so scared. I dreaded what would become of me and my family. I kept my mouth shut to protect us. He continued to assault me until he found another, younger girl. Only then did he let go of me,” Reem said.

Reem’s is only one of innumerable stories of Syrian women who have been subjugated to sexual exploitation, physical and verbal harassment, as well as leering, in temporary accommodation centers (shelters for the displaced) in Damascus and its surrounding rural areas. Women are coerced to have sex with shelters’ supervisors and officials in return for humanitarian aid. They are pressured to keep quiet, out of fear of being thrown out, defamed, and their aid cut off. They even risk being arrested, should it ever be discovered that they spoke up.

Women’s ordeal is aggravated by the shelters’ strict regulations. They are not allowed to leave, even for a few hours, unless they submit an official request, the approval of which hangs on the management’s whim. This prevents women from finding a job to insure a decent life, escape sexual oppression and the abominable conditions inside the shelters, as I have been told by five such women we met.

During my successive visits to several shelters in Damascus and its rural areas, I have interviewed eight women who have been forced by male managers and supervisors to yield sexual concessions. Throughout this investigation, I have also met with thirty-five male and female volunteers at the shelters, who unanimously corroborated the systematic scale on which sexual extortion is practiced in exchange for food for displaced women.

But it was impossible to confront the officers in charge of the shelters with such revelations. That would put the victims’ very lives at risk, as well as compromise my own safety.

A report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), titled “Voices from Syria 2018”, upholds that humanitarian aid is being exchanged for sex in many regions in Syria.

The detailed document reveals that “women and young girls inside these shelters are being sexually harassed and exploited by those in positions of authority in return for housing and aid. The most vulnerable are those “without male protectors”: widows, divorcees, and the displaced.”

According to another study commissioned in 2014 by UNHCR, one in every three Syrian women never left her house, or only did so in cases of extreme necessity, for fear of harassment and insecurity.

In yet another study, conducted by UNFPA, in cooperation with the Syrian Ministry of Social Affairs, titled “Situation of Women in Temporary Accommodation Centers in Damascus”, it is shown that 3.5% of women have been sexually exploited after coming to these shelters, including being subjected to leering, and verbal and physical harassment.

The night of the rape

On the morning of January 24th, upon a visit to a shelter hosting over 500 displaced families, I sat with a group of women who told me about the sexual concessions they have to make in order to receive their share of the aid. None of them dared to go into specifics. But perhaps Um Saad, a strong woman in her 40s, speaks for all about the extent of the tragedy when she asks “Who will save us from retaliation if we speak up? And who will defend our rights?”

Hanan, a 30-year old widow and a mother of two, has been living in a shelter in Al-Duweir, ever since the death of her husband compelled her to leave Mayda’a in September of 2014.

I met Hanan outside the shelter on 28 March. She had gotten the permission to leave for a few hours, under the pretext of taking her child to a doctor in Damascus.

Back in 2016, when she went to pick up her food portion, the distributor gave her only a fraction of it and asked her to come back at night for the rest. When she returned that evening, he raped her.

She says that what happened to her is absolutely indescribable: “I could not yell at him. He approached me and began to touch my body. My tongue was tied. I tried to push him away, but he persisted.”

Hanan came out of his room not daring to tell anyone about what happened. For weeks on end, she continued to be raped without any means to escape. For there was no alternative shelter.

Getting advantage of women in need

What emboldens the offenders the most is the absence of the family’s male breadwinner coupled with the women’s lack of any skills that would qualify them for a job and a decent life, leaving them with no other safety net than the basket of humanitarian aid.

35 year-old Huda left the shelter after she could not take the manager’s sexual assaults anymore. I met her shortly thereafter at her house, on 23 July, 2017.

Huda took refuge with her two children in a shelter located in the upscale district of Kafr Sousa in Damascus, after her husband’s death drove her to flee Ein Tarma in Eastern Ghouta, in 2013.

In 2015, the officer in charge of distribution began making advances on Huda. When the latter did not reciprocate, he tried again, offering to give her and her children everything they needed in return for one night with her. Upon her rejection, he retaliated by withholding her food ration for more than three months.

Try as she might to survive, borrowing money and food from neighbours, she could not make ends meet. Faced with two hungry children, she ended up accepting the offer.

In August of 2016, her 9-year old son was diagnosed with diabetes, “God’s punishment for what I have done,” Huda thought. She decided to stop seeing the officer, left the shelter in October, and rented a room in Jaramana. She has since been earning her living working in a sweatshop, and selling homemade food supplies. She was never able to forget the painful details of her ordeal inside the shelter.

Now the head of the Department of Forensic Medicine at Damascus University and the former head of the Syrian Forensic Medicine Authority Hussein Nofal, had declared in June of 2017 that violence against women and children has dramatically increased during the ongoing crisis. The chief reasons behind the upsurge being displacement and rising poverty levels which have forced many families to share housing with strangers or rent small rooms.

Anas has volunteered in three different centers after he ran away from Al Yarmouk Refugee Camp in 2013. He says sexual harassment is raging inside the shelters. He himself has witnessed women being pressured into having sex. Once he saw a woman knocking on the manager’s door in the middle of the night, a price she had to pay in exchange for a blanket, or an extra bottle of baby milk.

Fear of defamation

“I don’t want to ruin my own life,” said one woman I interviewed in September of 2017. She was sexually abused at a shelter in Al Tal city, north of Damascus, a couple months before.

Her words account for the obstacles I faced during the present investigation. They also elucidate why women refrain from denouncing their aggressors by filing complaints. Victims dread defamation. They are petrified of being hurt, arrested, or even excommunicated. Society here blames the victim. Even the woman’s family themselves would shun her.

Thanaa, a woman in her thirties who escaped Meda’a to a shelter, says: “I didn’t dare to tell anyone about what happened to me. I was so scared. He used me repeatedely for sex. I care for my children. I am scared of him. He manages the shelter. He can kick us out anytime. We don’t have any other place to run to. Not to mention that he’s capable of writing a spiteful report against me and have the police land me in prison.”

Victims’ stories vary. So do the facets of their suffering. But one element is common to all: fear.

Wedad, 35 years old, is a volunteer with the Syrian Red Crescent. In 2015 and 2016, she worked at a shelter in Rural Damascus. With her own eyes, she witnessed four women, between the ages of 20 and 40, being sexually exploited by the shelter’s supervisor.

The victims’ silence is the greatest hurdle to Wedad’s work. “I totally understand their fear, she says. They’re weak and vulnerable, especially the ones who have had their husbands killed, arrested or kidnapped. Those women are powerless, with no one to protect them. Their aggressors have power and privilege. Their links with the authorities scare the victims into remaining silent.”

“Who will save us from retaliation if we speak up? And who will defend our rights?”

A center for exploitation

Sociologist Aliaa Ahmed calls these shelters “centers for sexual exploitation of women.” What pains Ahmed the most is the way in which the victims seek to cover up the crime, in order to avoid being blamed. Society’s attitude toward rape victims is to condemn the victims themselves: “if she had behaved decently, none of this would have happened to her.”

Ahmed points out that “it is a common belief that in the absence of a law that protects women’s safety, only their men can fulfill that function. Some women live alone with their children in shelters, which makes them an easy target for perpetrators.”

She explains that “assailants do not stop at anything to coerce women into sex, using force against those who refuse to submit to their repugnant desires. They know that if a woman decided to denounce them, she would be inviting the worst consequences upon herself, and herself alone. Noting that poor, displaced women in general is the group that is most vulnerable to sexual exploitation. Women coming from areas controlled by opposition fighters are at an even greater risk. Against the latter, “political reasons” and “security concerns,” are threatening tools for sexual extortion. “Terrorism” charges are always ready to be doled out to them. They are totally helpless.”

And she adds: “In such circumstances, many women find themselves obliged to submit to their assaulter and remain silent, or else escape and start a journey of endless torment, where they will have to face innumerable risks in search of alternatives that are equally bad.”

Silencing the voices

I contacted Kafr Sousa Police Department to inquire about the number of complaints filed by sexually exploited women. An officer who has served at the department between 2014 and 2015, proclaimed that they have received no more than five complaints from women living in shelters, all concerning “problems” with the shelters’ supervisors.

He added that whenever the police called on the shelter to see these women and issue a proper citation, the supervisor would immediately take the patrol chief aside, and persuade him to drop the issue, belittling it as mere “women trouble.” The case would end here. No further proceedings, no official investigation. Nothing is even documented, thus depriving the abused of her right to file a formal complaint and pursue her case in court.

The policeman observed signs of abuse visible on women who come to file complaints: a messed up hijab here, torn and dirty clothes there, tears, and refusal to tell what happened.

His daily chats with colleagues at the police station leave no doubt that shelters’ supervisors have clout and are more powerful than chief patrols. He and his colleagues have heard numerous stories about women being subjected to sexual abuse as a price for the food aid, the distribution of which is personally controlled by supervisors.

On the other hand, four women from an Adra al- ‘Amaliyah shelter North of the capital filed a complaint against the supervisor who forced them to have sex with him and threatened to expulse them if they refuse, according to volunteers who have witnessed the complaint.

The governorate of Damascus and the Supreme Committee for Relief investigated the issue with residents at the center. But then, the case was closed, as if nothing had happened. The supervisor remained in his position. It was later discovered that the grievants were expelled from the center.

I was not able to find those women. And when I inquired about them at the governorate’s offices, the officer refused to cooperate, claiming we were dealing here with “classified information.”

Minor girls were also molested

I met five girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who have been sexually harassed, one by an officer, the other four by residents and workers of the rural Damascene shelter, back in 2016. None of them dared to tell anyone except their mothers who asked them to keep quiet out of fear for their reputation, and the danger of expulsion.

13-year old Walaa is one of those girls. She and her family were displaced from Adra in 2013 and settled in a shelter near Damascus. Walaa lives with her mother and siblings in a small room. Her mother double-locks the door at night. She lives in fear for the safety of her daughters, ever since her husband was detained in 2014 and she has been kept in the dark about his fate.

Walaa’s mother felt utterly helpless when her daughter came home in tears one day after being molested by the supervisor who gave her the family’s food portion.

Walaa recounts: “first, when he talked to me in a weird way, I didn’t care. I was very tired from the long wait. I was thinking about the dinner my mother was preparing, and I wanted to take the basket and leave quickly, especially that mother always warned us not to hang around the center after sunset. But then he began to touch me. I tried to scream but he put his hand on my mouth and touched my private parts.” She continues, “ I went to my mom. We cried a lot. We didn’t dare take any action. My father has been missing for three years. We know nothing of his whereabouts. Those people can harm us. No one is here to protect us. What can we do?”

Psychological effects

Psychiatrist Mohammed Mohsen reflects on the psychological damage of sexual extortion: “the victim feels oppressed and neglected. Replaying the details of the assault in her head can result in severe depression as well. In some cases, stress, anxiety, and a gloomy view of life could lead to suicide. The psychological harm resulting from sexual coercion needs serious medical attention.”

The law forbids but filing a complaint is impossible

In its “Public Morality Crimes” section, Syrian law distinguishes between “rape” and “honor crime.”

Given the “coercion” element in sexual extortion, the penal code classifies it under “rape.”

However, “in the absence of a clear mechanism for filing complaints, we have lost all hope that those committing such atrocities be held accountable for their crimes,” said Basema Jabry, a board member of the Syrian Women Network.

Conditions of coercion or menace in the Syrian law

“Non-consent necessarily implies physical coercion by violence or threat, or moral coercion, or abuse of power, or abuse of minors. In the absence of these acts, the offender cannot be punished.” (Resolution 886/1984 – Basis 1194 – Court of Cassation – Criminal Chambers – Syria.)

Jabry emphasizes that the law is on the victim’s side, were she to have to courage to report the crime. She adds, however, that “the fears that hold sway over the victims are justified: from fear of parents who play a negative role, to fear of society and defamation, and finally the fear of the offender himself, especially if he is in a position of power.”

*This report was produced with the support of “Open Media Hub”, funding from the European Union, and supervision from Ahmad Haj Hamdo– SIRAJ. Published on Daraj