In the autumn of 2025, after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Abdulhadi Abu Harb returned to his hometown of Daraya in the Damascus countryside for the first time since he had been forced to leave in 2012 under relentless helicopter bombardment with barrel bombs.

He stood for a long time before a charred wall that had once been part of his home. He ran his hand over the stones, searching for a trace of a color he remembered, for a mark confirming that this place had once been his house. But it was not only time that had changed. Streets had been renamed, houses had new occupants, and ownership — once an unquestioned right — had become a matter of dispute.

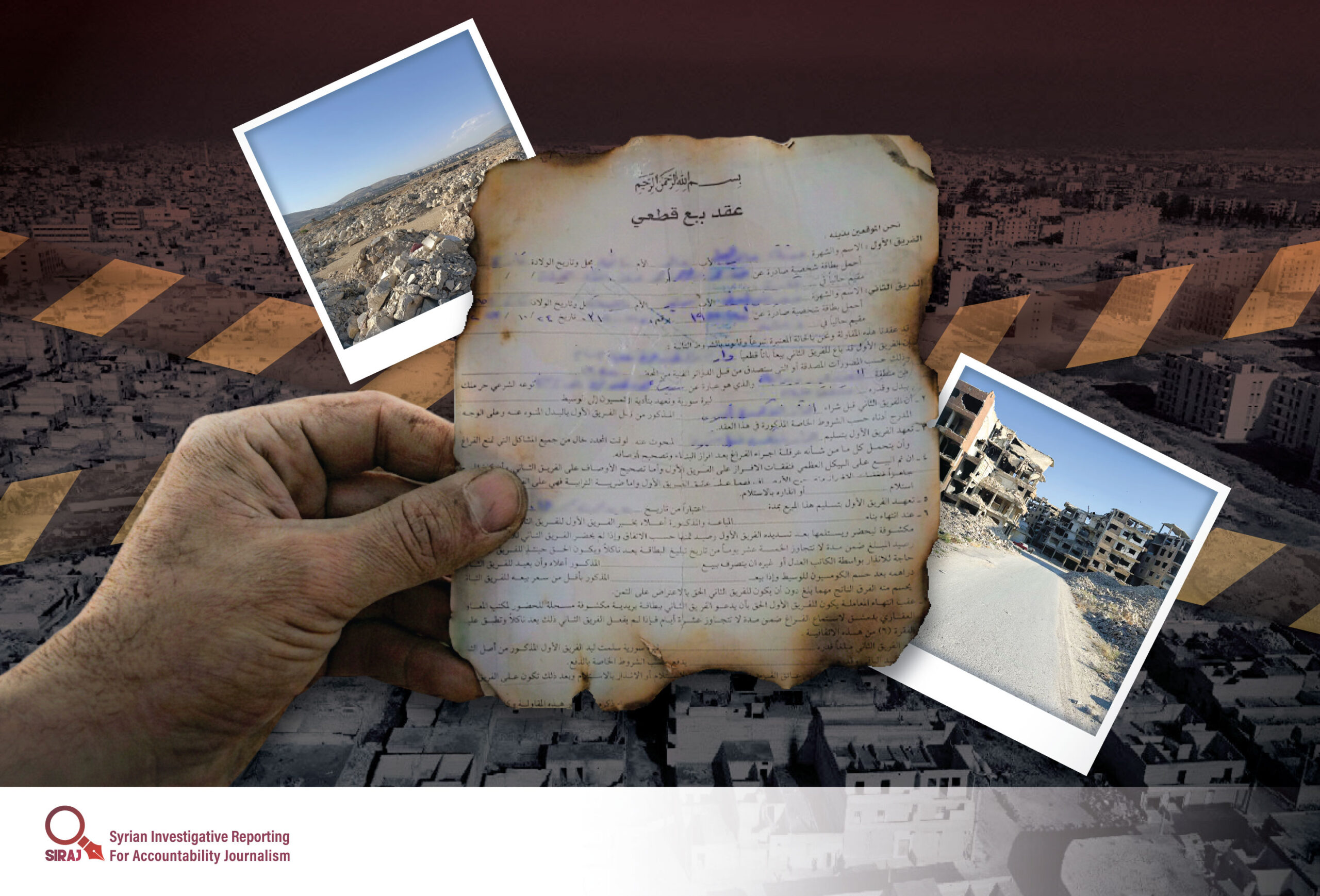

Before his displacement, Abu Harb had carefully kept his purchase contracts and ownership documents. He bought his first house in 2010 after years of work and migration abroad, paying for it in cash. The second house was the family home he inherited from his father, and its papers remained preserved even after they were forced to flee.

Upon his return, however, he discovered that the first house had been renovated and occupied by strangers after it had been “sold” during his absence through an intermediary who later died, breaking the legal chain of ownership. As for the family home, it had burned during the years of siege, then was restored and sold multiple times using forged contracts.

“We lost the house three times,” Abu Harb says. “The first time when we left under the bombing. The second when it burned. And the third when we found it in someone else’s hands. It’s like losing memory itself… not just the walls.”

Abdulhadi’s story reveals a broader crisis faced by thousands of Syrians who returned after the regime’s fall, only to discover that the road back to their homes was obstructed not only by rubble, but by a complex web of laws, missing records, and sales and forgery schemes that exploited their forced absence during the war years.

In this investigative report, drawing on personal interviews, analysis of property ownership documents and complaints, and a review of laws and government decisions, we examine how the loss of documentation during the war has prevented thousands of Syrians from reclaiming their homes today. Many are unable to prove ownership of properties that, in many cases, were transferred to strangers during their absence, with ownership altered or homes seized because they stood vacant.

The suffering is compounded in informal housing areas in Damascus and its suburbs, where most sales, purchases, and transfers took place outside official institutions through customary contracts not registered in real estate courts, due to the absence of formal title deeds known as the “green tabou.” Similar complications arise in areas subject to urban redevelopment plans imposed under complex regulatory laws.

Through interviews with families from various areas of Damascus and its countryside, the investigation shows how proving ownership of one’s home, once among the most basic of rights, has become one of the most complex legal and humanitarian battles in Syria today, particularly in neighborhoods subjected to systematic destruction during the war.

Anwar Majni, a judge specializing in real estate and property rights, explains that the problem lies not only in lost documentation but also in the legal framework itself: “There are around 200 laws in Syria related to property issues, some of which contradict one another. This heavy legacy makes finding comprehensive solutions extremely difficult. We need a unified property law.”

Return Without Papers: The Battle for Ownership After the Fall of the Regime

As waves of return began to reach Damascus, its suburbs, and other parts of the country, it became clear that the loss of housing was not linked solely to widespread destruction, but also to many returnees’ inability to legally prove ownership of their homes.

The loss of official documents, the burning of real estate records, the absence of accurate inheritance registries, and the continued enforcement of laws enacted at the height of the war under the Assad regime have all turned the process of proving ownership into a long, costly judicial path, often with no outcome.

Legal expert Malek Al-Awda explains: “The core problem today lies in the loss of property documentation. Thousands of original documents were damaged, burned, stolen, or forged. In the absence of written evidence, the owner has no option but to turn to the courts, a slow and exhausting process.”

In November 2025, the Ministry of Justice issued a circular to heads of judicial courts across the governorates, outlining mechanisms for restoring the records of certain notary offices that had been damaged or lost. The circular stipulated that any request for restoration or re-registration would only be accepted upon submission of a certified “true copy” of the missing document. If such a copy was unavailable, the request would be rejected and the applicant referred to the courts to pursue their claim.

For many returnees, however, these conditions appeared nearly impossible to meet, particularly in areas where courts had been destroyed or their records completely burned.

How Are Properties Classified When They Become Subject to Dispute?

In cities such as Daraya, several residents interviewed by the investigative team confirmed that they no longer possess any documents proving ownership of their apartments or homes, after the records of the Sharia Court and the notary public office were burned during the siege of the city between 2013 and 2016.

With official records gone, proving ownership has shifted from an administrative procedure to an open-ended judicial dispute.

Flora Diop, Assistant Director of Legislation and Real Estate Registration at the Directorate of Real Estate Interests in Damascus, believes that Abdulhadi Abu Harb’s case is solvable as soon as a copy of the title deed is retrieved from the land registry. The forged contracts mentioned were most likely concluded outside official records and therefore carry no legal value. Based on the available information, she argues that Abu Harb may not even require court intervention, as his case appears straightforward and clear.

Homes Sold in the Shadows: Forgery and the Exploitation of Absence

The loss of property did not stem solely from burned documents or missing records; it was compounded by fraudulent sales and forgery carried out during years of forced absence. In Abdulhadi Abu Harb’s case, the house was not merely “seized”; it was also transferred through sales contracts brokered by intermediaries who later died, breaking the legal chain of proof. The family home, meanwhile, was sold multiple times using forged records.

Lawyer and legal expert Hind Al-Saleh explains that this legal vacuum opened the door to organized networks: “Networks of brokers and intermediaries spread, exploiting the absence of property owners. They re-registered homes through illegal means or transferred ownership using forged powers of attorney and substitution contracts.”

In April 2023, an investigative report by the Syrian Investigative Journalism Unit, SIRAJ, in collaboration with the British newspaper The Guardian, revealed the existence of more than 20 security-linked networks specializing in property ownership forgery in several Syrian cities under the control of the now-fallen Assad regime.

The joint investigation noted that the absence of centralized judicial records means there is no comprehensive data on the scale of property theft in Syria or the seizure of homes belonging to Syrians living abroad.

A source at the Syrian Ministry of Justice told the investigative team that a specialized court will be established in 2026 to investigate forgery operations that took place under the former regime, to restore properties to their original owners. The source added that thousands of properties had their ownership falsified and were sold through illegal transactions.

Engineer Mazhar Sharbaji, a unionist and former mayor of Daraya, warns of the dangers of compounded forgery in certain areas: “In some neighborhoods, you may find someone who owns two or three shares in a property, yet sells the entire property by falsifying the number of shares. These cases make proving one’s rights later nearly impossible.”

Since the outbreak of the 2011 uprising, Bashar al-Assad’s regime issued 35 laws permitting the confiscation, expropriation, and seizure of property. These laws related to counterterrorism measures, urban planning, regulation of informal settlements, debt collection, enforcement of compulsory military service, communal agricultural lands, and property registries. They primarily affected the properties of displaced persons and alleged political opponents.

In such cases, returnees find themselves facing an unequal battle: their original documents are missing, official records are either damaged or contradictory, while the opposing party holds “formal” contracts that were processed during years of chaos.

Laws That Undermine Property Rights: Wartime Legislation as a Tool of Silent Dispossession

Syria’s property crisis did not emerge from chaos alone. It was shaped by a legislative framework crafted during the war years and used to expand the seizure of assets belonging to opponents and displaced persons, facilitating the confiscation of their properties or their sale at auctions of which the owners were often unaware.

Since early 2011, the government of the now-fallen Assad regime issued a series of laws and decrees related to property rights. These included measures authorizing the seizure of movable and immovable assets belonging to political opponents or individuals accused of supporting “terrorism”, charges widely used to criminalize opponents, activists, and entire communities.

Counterterrorism Law No. 19 of 2012 stipulates in Article 12 that, “In all crimes provided for in this law, the court shall, upon conviction, order the confiscation of movable and immovable assets, their proceeds, and items used or intended for use in committing the crime.”

For legal experts we spoke to, this provision was not merely a criminal penalty, but a gateway to broad asset seizures within a wider political context. It affected thousands of families who left the country or were internally displaced, particularly as Article 11 of the same law authorized the “competent Public Prosecutor or their delegate,” even before any final judicial ruling, to “order the freezing of movable and immovable assets of anyone who commits one of the crimes related to financing terrorist acts or any of the crimes stipulated in this law,” based solely on their assessment that “sufficient evidence exists,” under the pretext of safeguarding the rights of the state and victims.

This expansion of confiscation outside the judicial process was reinforced by Legislative Decree No. 63 of 2012, which granted judicial police authorities, during investigations into crimes against state security or those covered by Law No. 19 of July 2, 2012, the power to submit a written request to the Minister of Finance to take precautionary measures against the movable and immovable assets of the accused.

For example, lists published by the Ministry of Finance revealed 40,000 precautionary asset seizure cases affecting Syrians in 2017 and 30,000 in 2016, most of them justified by what the regime described as “involvement in terrorist activities.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, constitutes one of the foremost international frameworks protecting individual property rights, particularly under Articles 8, 17, and 25. These protections are further reinforced by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the 1969 American Convention on Human Rights, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

At the national level, the Syrian Constitution protects the right to private property under Articles 15, 16, and 17. These protections are further supported by the Syrian Civil Code and Urban Planning and Development Law No. 23 of 2015.

The restitution of property for refugees and internally displaced persons is a standalone right under the Pinheiro Principles, adopted in 2005 by the United Nations Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights.

These principles affirm the right to recover housing and property that was arbitrarily lost, or, when restitution is factually impossible, to receive compensation determined by an independent and impartial court.

In this context, Sharbaji warns that the property crisis cannot be treated as a single, homogeneous file. Each area carries its own story and distinct complexities — particularly regions that experienced large-scale displacement followed by partial returns, or shifts in controlling authorities. These conditions created an ideal environment for record forgery and the exploitation of legal loopholes.

Urban Planning Pretexts… Erasing a Neighborhood from the Map

Alongside laws targeting the properties of opponents and displaced persons, urban planning legislation played an additional role in reshaping ownership on the ground, especially in areas surrounding Damascus. There, complex redevelopment projects were imposed, and entire neighborhoods were classified as “informal zones” subject to demolition or restructuring.

Legal experts point in particular to Law No. 10 of 2018, which authorized the establishment of redevelopment zones and the conversion of property ownership into shares within a regulatory master plan, subject to a limited deadline for proving ownership. The law previously raised widespread fears of dispossessing displaced persons and refugees of their property, particularly amid a lack of trust in procedures under the former regime.

Law No. 23 of 2015 (Urban Planning and Development Law) is also significant. It regulates land preparation for construction in accordance with regulatory plans, whether through subdivision or reorganization. It stipulates that land included within a redevelopment zone becomes jointly owned by rights holders in proportion to the assessed value of their original properties.

On the ground, however, in areas such as Daraya and its surroundings, residents report a sense of injustice in compensation and alternative housing processes. Procedures move extremely slowly, while administrative conditions and requirements accumulate atop an already complex reality marked by damaged ownership records and missing official documentation.

In interviews with eight families, many emphasized that these problems did not originate in the current phase. Their roots trace back to the Assad era, when property and compensation files were managed through a bureaucratic and security-driven system that produced widespread legal chaos. Yet the continued reliance on these mechanisms, without substantive reforms to date, makes the issue appear, in the eyes of those affected, as a present failure, even though it is in fact a heavy legacy inherited by the current government, which has not yet succeeded in dismantling it.

Al-Khaleej Neighborhood… Destruction Is Not the Only Problem

At Daraya’s entrance from the Damascus side, adjacent to Mezzeh Military Airport, the Al-Khaleej neighborhood, an informal residential area stretching toward Mezzeh, was among the areas most completely destroyed. Today, it appears as little more than a trace: homes erased, rubble cleared, the landmarks of an entire neighborhood wiped from the map.

The question of compensation remains unresolved: How will homeowners be compensated for houses destroyed during military operations? And what authority will confirm that a house once stood here if documents are lost, records damaged, and the neighborhood itself erased?

Abu Rashed, a Daraya resident who recently returned from ten years of exile in Turkey, says he recognized the location of his home by a large tree that once stood in front of it and remains to this day. Another man identified his house by the rare-colored tiles and marble he had installed when he built it. Both, like many others, returned first to confirm that the place still existed, before beginning to ask about the paperwork.

Mohammad Abu Malek, a resident of Daraya, specifically the Al-Khaleej neighborhood, was displaced with his family to Idlib in 2016, before undertaking a sea journey to Europe in search of safety, work, and education for his children. After the fall of the regime, he felt for the first time that returning might become possible.

“For years, I carried the idea of the house in my head because, for us, it holds all the memories connected to Syria,” he says. “I thought, finally, we’ll go back and start over. I returned to Daraya imagining that the hardest thing I would face was the destruction in Al-Khaleej… but I discovered that destruction is not the biggest problem.”

Abu Malek recounts his first impressions: the neighborhood had become rubble, to the point that Mezzeh Airport was now visible from Daraya because Al-Khaleej had been “leveled to the ground.” Yet the deeper shock was not the rubble itself, but what that rubble meant legally. “A house isn’t just walls… a house is a document. If you don’t have a paper, you effectively have nothing.”

Abu Malek’s house was completely demolished due to its proximity to Mezzeh Military Airport. It no longer exists, reduced to a mass of debris. Today, he possesses no document proving his ownership.

“Without an official proof-of-ownership document, I can’t do anything,” he says. “I can’t rebuild it, I can’t sell it, I can’t even submit a formal compensation request. It’s as if the house has become a trace, and I’m just someone trying to prove that I was once its owner.”

A Legal Trap

If urban redevelopment zones generate crisis by converting ownership into shares and slow compensation mechanisms, informal housing areas such as Al-Khaleej produce a different kind of crisis: ownership that is socially recognized but legally fragile.

Sharbaji explains that property ownership in Syria is not uniform. Some properties are formally registered (tabou), with existing documentation; others are recorded through notary offices and are supposed to have official real estate extracts. But a significant proportion of homes were sold through external or customary contracts that were never formally registered, making them difficult to prove before the state.

In these areas, where transactions occurred outside official institutions, many residents do not possess the “green tabou,” nor do they have contracts registered in real estate courts. With the outbreak of war, this loophole turned into fertile ground for disputes, forgery, and the monopolization of rights.

Interrogation Before Return… Property Access Through Security Channels

During the war years, the battle to reclaim homes in Syria was not only about documents and records, but, in many cases, about navigating the security apparatus of the now-collapsed Assad regime.

In 2023, Abu Ahmad, a resident of the Tishreen neighborhood in Damascus, decided to return to live in his home despite the extensive destruction and the absence of basic services in the area. The high cost of living and the difficulty of paying rent in the capital pushed him to consider returning. But the path back to his house was not open.

Abu Ahmad learned from neighbors and the neighborhood mukhtar that he could not enter the area or even open the door to his home without first obtaining approval from Air Force Intelligence in Harasta. He underwent a security interrogation that included background checks on him and his three sons, and questions about any potential ties to the opposition or issues related to military service. After hours of questioning, he was allowed to return, in exchange for a bribe paid to security officers.

But another shock awaited him inside the house. “I found a family living in my home,” Abu Ahmad says. “They told me they had bought it from a real estate broker for a small sum.”

Abu Ahmad had purchased the three-room house, measuring around 60 square meters, in 2010 for 250,000 Syrian pounds, approximately $5,000 at the time. Today, he possesses no sale contract or official document proving his ownership. The house is located in an informal, unregulated area not subject to a formal land registry.

He is now trying to reclaim his home by proving that he is the rightful owner. But the path is complicated: the original seller died in 2013, there is no documented chain of contracts, no title deed, and no official registry to consult.

In such cases, Mazhar Sharbaji explains, courts may rely on alternative forms of evidence, such as electricity bills or water meters registered in the individual’s name, since obtaining a utility meter theoretically requires municipal inspection and confirmation of actual residence. Yet even these forms of proof do not guarantee a swift or decisive outcome.

How Do You Prove Ownership When You Have No Proof?

When written evidence — a title deed, a registered sale contract, or a prior court ruling, is absent, the judiciary becomes the only available path. Legal expert Malek Al-Awda explains that judges in such cases rely on what is known as “non-written evidence,” including interrogations, judicial investigations, witness testimony, and sworn statements.

“These procedures take a long time,” Al-Awda says, “and they do not always guarantee a quick result, which temporarily deprives the owner of the ability to use the property, whether for housing, sale, or renovation.”

In practice, many returnees find themselves in a state of “legal limbo”: unable to reclaim the home, unable to dispose of it, and unable to obtain compensation. With prolonged litigation, claiming one’s home shifts from being an obvious right to becoming a psychological and financial burden.

What Is the ‘Green Tabou’?

The “green tabou” is considered the strongest proof of real estate ownership in Syria. It is a copy of the official property registry record and is issued only once. If lost, the owner must request a replacement for a lost document.

The deed includes the property number, its size and location, the owner’s name and share, and all encumbrances on the property, such as seizures, lawsuits, or mortgages.

However, in vast areas where land registry offices themselves were destroyed, this document, meant to serve as a guarantee, has become a missing paper that cannot easily be restored.

Inside the Palace of Justice in Damascus, where the investigative team visited notary offices and court departments, the scene was telling: long queues, worn-out files, and citizens moving from office to office in search of legal advice or a procedural thread that might restore part of what they lost.

Most of those we met were recent returnees after the regime’s fall, confronting a recurring reality: missing or damaged ownership records, homes occupied by strangers, and legal frameworks still operating under exceptional wartime logic. It is a reality that reflects a deep gap between what people expect from justice and what the inherited legal structure currently allows.

Millions Affected by Destruction

The property crisis in Syria extends far beyond individual stories; it spans the entire nation.

According to Abdallah Al-Dardari, Assistant Secretary-General and Director of the Regional Bureau for Arab States at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Syria had approximately 5.5 million homes before the war. Of these, 328,000 were completely destroyed, meaning that one in every three homes suffered either total destruction or partial damage.

As a result, around 5.7 million people today require direct housing support — either because they are homeless, living in uninhabitable dwellings, or at risk of losing their property due to missing documentation and complex ownership disputes.

Mu’tasim Al-Sioufi, a director at the organization The Day After, argues that the crisis goes beyond physical destruction to a deeply complicated legal structure: “Around 60 percent of housing in Syria consists of informal settlements. Many of these homes were connected to water and electricity in the 1980s due to corruption. Then came the war and displacement, which further complicated matters, in addition to longstanding issues such as usufruct rights and expropriations dating back to the 1960s.”

According to Al-Sioufi, what emerged after the regime’s fall is only “the tip of the iceberg,” while the real crisis runs much deeper and is far more intertwined.

A table by “Syrian Response Coordinators” showing estimates for Syria’s reconstruction costs as a result of the destruction caused by the Assad regime.

The Legacy of Systematic Looting… The Fourth Division and Beyond

In February 2025, the United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria issued a report titled: “Pillage and Plunder: The Unlawful Seizure and Destruction of Refugee and Internally Displaced Persons’ Property in Syria.”

Based on satellite imagery, direct testimonies, and visual documentation, the report documented systematic looting and destruction of civilian homes over a period of 13 years. It concluded that such looting — often linked to military and security formations, including the Fourth Division — represents one of the major obstacles to the return of millions of refugees and displaced persons following the regime’s fall.

According to the report, the areas most severely affected were those that changed hands between 2016 and 2020, where properties were treated as “spoils” or instruments of collective punishment.

A Home Waiting for a Paper… Return Without Guarantees

In response to this landscape, the Ministry of Justice speaks of measures to address the problem. A ministry source — who requested anonymity — stated that the Public Prosecutor’s Office and relevant judicial authorities are pursuing cases of unlawful property seizure, particularly those belonging to forcibly displaced persons, “in accordance with applicable laws and through procedures that ensure justice and transparency.”

According to the source, specialized courts and judicial departments have been designated to handle cases of forged property ownership and lost documents, with the aim of accelerating rulings and unifying judicial interpretations, while also simplifying procedures and reducing processing times.

However, legal experts and rights advocates argue that these steps, despite their importance, remain insufficient without more courageous decisions.

Al-Sioufi proposes expanding the means of proving ownership beyond traditional tools, such as incorporating broader community testimonies or establishing a technical reference body to develop clear, region-specific standards.

Malek Al-Awda stresses the need for transitional solutions, such as granting temporary ownership records valid for five or ten years to safeguard people’s rights until registry issues are resolved. “Without alternative and bold legal formulas,” he says, “thousands of families will remain locked out of their homes — even after they have returned.”

For Abdulhadi Abu Harb, Mohammad Abu Malek, Abu Ahmad, and many others, return remains incomplete. The house exists — or once existed — but the paper is missing. In its absence, memory turns into dispute, belonging into a file, and a right into a long judicial process.

In post-regime Syria, returning home is no longer a simple act. It is a legal, social, and psychological battle — one that risks reproducing displacement in a silent form, this time in the name of the law.

This investigation was produced with support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), and a version of it was published on the Daraj website.

- Research and reporting: Mawaddah Kallas

- Creative coordination and visual solutions: Radwan Awad