By Hamoud Almahmoud, Delphine Reuter, with Catalin Prisacariu, Giampaolo Musumeci, Frédéric Loore, Jean-Yves Tistaert, Nikolia Apostolou and Safak Timur

+ This cross-border investigation was completed with support from Journalismfund.eu and cooperation from the Amman-based Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ).

Alhayat– On the night of December 30, 2014, an Italian coast guards helicopter is flying towards a cargo ship heading towards Italy. The cargo ship, called the “Blue Sky M”, did not answer any of the calls asking for identification. There might not be a pilot onboard the vessel. The wind and the stormy sea are challenging the Italian officers. There is a creepy feeling in the helicopter: it could be a kamikaze cargo ship – with explosives onboard.

Once the Italian coast guards are dropped onto the deck of the ship, they find a group of passengers huddled together in the hull of the ship. They understand that the “Blue Sky M” is another cargo ship transporting migrants towards Europe. Once they take control of the ship and sail it to Gallipoli, the police come onboard to identify the person responsible for the smuggling. And they arrest its captain, Rani Sarkas.

“We will never forget that night, never”, said a representative from a humanitarian agency who was on board the dock when the ship arrived in Gallipoli. “There were 60 children along with a woman gave birth during the trip.”

The price the migrants paid for this short journey is hefty: All the passengers of the “Blue Sky M” seemed to have paid between $4,500 and $6,000 dollars each. The smugglers put 768 migrants on the “Blue Sky M” pocketing between $3.5 million and $4.6 million. A source in the Italian coast guards told us that a cargo ship like the “Blue Sky M” is the perfect means of transportation for the smugglers. They maximize profit and minimize risks, even for the crew: it’s easier for them to disappear and hide amidst the crowd.

An Italian source in the judiciary told us that the crew that operated the “Blue Sky M” for the smuggling operation probably earned about $5,000 each, whilst the captain, Rani Sarkas, made $25,000, just like Ali Assi Amer, the chief engineer, who escaped. Sarkas wasn’t as lucky or skillful as other smugglers: he was jailed and is still awaiting trial. He told the police that the money was given to his wife, who lives in Tartous, Syria. Sarkas’ family may have also collected the payment for other crew members in this smuggling operation.

Sarkas, a father with connections in various ports, also acted as a middleman for the purchase of old cargo ships on behalf of clients in the Middle East. In mid-2015, Sarkas worked with the owners of a ship called “Haddad 1” when they were trying to sell it. In September 2015, the “Haddad 1” was seized by the Greek authorities after they raided the ship and found it was carrying weapons. The ship was escorted to the port of Heraklion where more containers filled with 5,000 rifles were discovered. It has remained there ever since.

Rani Sarkas told the Italian authorities that he had been recruited via a man named Abu Haidar, based in Tartous, to carry out the smuggling of migrants. He said Haidar is the head of a “Syrian agency”. Our Italian source told us that Rani Sarkas seems to be covering for someone bigger than him; someone who has piloted the smuggling operation from A to Z.

THE NETWORK

Over the past four months, a team of eight journalists from six countries and a specialist in human trafficking have worked on uncovering the people and companies who are making a profit from selling often hazardous journeys to the migrants and refugees who hope to cross the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe. Some of these trips end in disaster, with ships capsizing or sinking, killing most of their passengers. In April 2015, 800 migrants had drowned when their ship capsized off the coast of Libya.

The team has met with prosecutors investigating these cases, has dived into trade and company registries, cross-checked with the information found in various shipping databases, and came up with a list of suspicious ships that were used to carry migrants or have been blacklisted because of their illegal activities. Some ships were banned from entering European territorial waters because they had broken maritime safety rules; others broke embargoes imposed on Syria; others yet were identified by the UN Security Council after coast guards investigated them for weapons trafficking. We have found at least one instance where the ship belongs to a company linked to a criminal organization.

The team found out that at least 17 cargo ships left from Turkey between September 2014 and January 2015 illegally carrying migrants. They include: “Sandy”, “Paris”, “Zain”, “Vitriol”, “Merkur 1”, “Tiss”. Every other week, rescue operations were taking place. In total, at least 6,000 migrants boarded those ships, which are old and not well-maintained. Almost all of them were Syrians. All came from Turkey.

The “Blue Sky M” passengers were embarked on the southern coast of Turkey, close to Syria. The smugglers used small boats to commute the migrants back and forth from the beach of Mersin to the anchored cargo ship.

The people who are making money out of this migrant smuggling business are mostly Syrians, originally coming from Tartous and Latakia, Syria’s two biggest ports stuck between Lebanon and Turkey on the Mediterranean coast. This loose organization of smugglers brings together ship owners, import and export agencies, seamen-for-hire, captains, and all kinds of middlemen working in collusion to benefit from the increasingly profitable migrant smuggling business.

Some of the cargo ships that were used to carry migrants from Turkey to Europe belong to the same shipping companies. This points to the existence of a loose network of organizations and companies working together.

The “Blue Sky M” was sold and bought by people belonging to a group of businessmen based in Constanta and Galati, Romania. All are shipping professionals, some of whom have been linked to dubious businesses, including weapons trafficking.

The port of Constanza, on the Black Sea, has long been a refuge for all kinds of illicit activities and an entry point to the EU. The team of journalists was able to track back the backbone of the organization to Constanza and Galati, where the Syrian diaspora is very active. Amongst the Syrians who are operating the human trafficking business and some are linked to weapons and cigarette smuggling. Several have been criminally convicted.

THE ROMANIAN CONNECTION

In 2011, Saleh Emad, a Syrian living in Galati, bought the “Blue Sky M” from Bittar Ahmad, 51, a Romanian national originally from Talkalakh in Syria. Bittar Ahmad used to transport timber for Mustafa Tartousi, 54, who owned shipping companies in Constanza. In November 2014, Tartousi was convicted to seven years in prison for helping his business partner, Omar Hayssam, escape conviction in Romania for the kidnapping of three Romanian journalists in Iraq in 2005. Hayssam boarded a ship belonging to Tartousi, the “Iman T”, and fled to Egypt. In 2008 he was convicted in absentia to 20 years in prison. His escape forced the chief prosecutor and the heads of the Romanian secret services to tender in their resignation.

Bittar Ahmad was interrogated by Romanian prosecutors in the Hayssam case in 2006, and during Tartousi’s trial in 2014.

Saleh Emad then contracted Mikhael Deaibes, a Lebanese living in Constanza, to be the agent not only for the “Blue Sky M” but also for two other ships, the “Blue Sky S” and the “Blue Sky E”. Saleh Emad also contracted a company called Info Market Srl to take care of the paperwork of his ships. Info Market is mentioned in various shipping databases as the owner of the “Blue Sky M” even though it’s not Saleh Emad’s company. His company is called Syrom Shipping.

In 2014, according to Mikhael Deaibes, Saleh Emad sold the “Blue Sky M” in Turkey, using an offshore company based in Panama, Blue Sky Shipping Int. SA, to record the transaction. With the profit of the sale, Saled Emad bought apartments in Constanza, according to Deaibes.

Another Syrian, Ahmad Haj Hamoud, 31, might be the person who bought the ‘Blue Sky M” from Saleh Emad. We got a copy of his passport from a Romanian source and it was later confirmed by the Moldovan Ministry of Transportation via email. We cannot be certain: the ship was sold using offshore companies; the buyer hiding behind Junos International Inc., a company created in Belize, and the seller using Fairway Navigation Ltd., based in the Marshall Islands. All we know for sure is that the sale took place on 8 December 2014, three weeks before the ship arrived in Italy. Junos International Inc. was set up especially for this transaction: it only appeared on the Belize company registry on 18 November 2014.

The smuggling operation began soon after the sale of the “Blue Sky M” to Ahmad Haj Hamoud. At the time of the sale, the ship was in the port of Varna, Bulgaria. It then sailed through the Dardanelles, the inlet connecting the eastern and western part of Turkey, and towards Mersin. On December 20, the ship had an engine failure off Tasucu, a port on the southern coast of Turkey – at least, that is what the crew communicated to the port authorities. Tasucu is a small port located 100 km to the west of Mersin. On 28 December, with the migrants probably onboard, the ship first sailed towards Greece, then headed to Italy. Two days later, it was rescued by the Italian coast guards.

CAGED IN

On 1 January 2015, only a few days after the “Blue Sky M” arrived in Gallipoli, the coast guards take their helicopter to rescue a ship that had no fuel left and was adrift in the Mediterranean. At 3 am in the morning, they attempt to take control of the ship. There is no electricity on board. The coast guards move around with torches, knowing that being on the ship isn’t safe.

“It was an extremely dangerous situation”, one of the coast guards told us.

The “Blue Sky M” and the “Ezadeen”: both ships made headlines when they arrived in Italy after being rescued by the coast guards. The “Blue Sky M” was a cargo ship, so the migrants travelled inside the dark cargo holds of the ship. The Ezadeen was a livestock carrier: the ship smelled of excrements and the windows were lined with steel bars.

The ship is towed to Corigliano Calabro. A coast guard who was waiting on the dock when the ship arrived told us that he had never seen anything like it. The passengers had been sailing towards Italy literally caged in, the floor of the ship patchy with the droppings left behind by the cattle which the “Ezadeen” had previously carried. The migrants’ fingers were squeezed around the steel bars that were covering the openings in the hull of the ship. Those who could afford to pay more had stayed in the cabins of the crew. The coast guards count about 400 people on board. But they find life jackets for only about 100 passengers.

According to our Italian sources, the “Ezadeen” also left from Mersin. In a shipping database, we see that the ship left Tartous, Syria on 21 October 2014, and didn’t reappear on the radar until 8 December, in Cyprus. It left Cyprus on 17 December, presumably for Mersin.

According to sources close to the investigation into the “Ezadeen” in Italy, the crew onboard the livestock carrier disappeared with the crowd of migrants once they reached the port of Corigliano. WIth the disappearance of these key witnesses, finding out who organized the smuggling mission has become very difficult for the authorities.

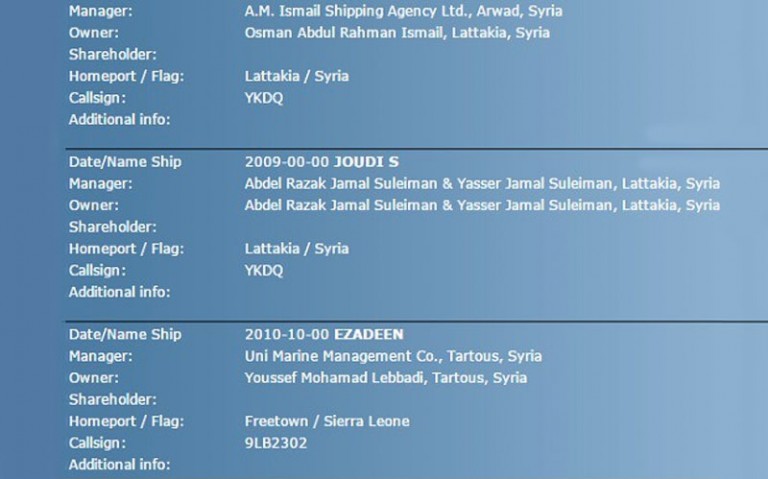

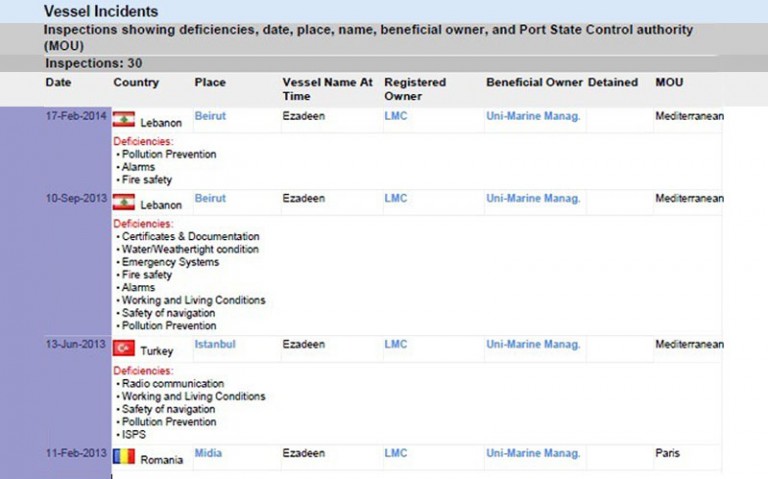

However, two companies behind “Ezadeen” can easily be traced: Lebbadi YM and Uni-Marine Management Co., both located in Tartous, Syria. Youssef Mohammad Lebbadi, a Syrian citizen, is the owner of the “Ezadeen”, which he bought when it was still named “Joudi S.”, according to a Dutch shipping database. His company, Lebbadi YM, used to be located at 726 Al Mina street in Tartous, the same address as for Uni-Marine. Today, he has dissolved his company and moved to Dubai where he founded another company, Lebbadi Shipping & Ship Management. We were unable to reach Mr. Lebbadi for comment.

The owner of Uni-Marine Management Co., the second company behind the “Ezadeen”, is 52-year-old Abdallah Allouf. Allouf told us he delivered safety certificates for the “Ezadeen” through Uni-Marine. He has another company, Allouf For Safety (or AFS Shipping services), located at the same address as Uni-Marine. Actually, Uni-Marine shares the same address as at least seven other companies with different owners, including thus Lebbadi YM, and each company has its own vessels.

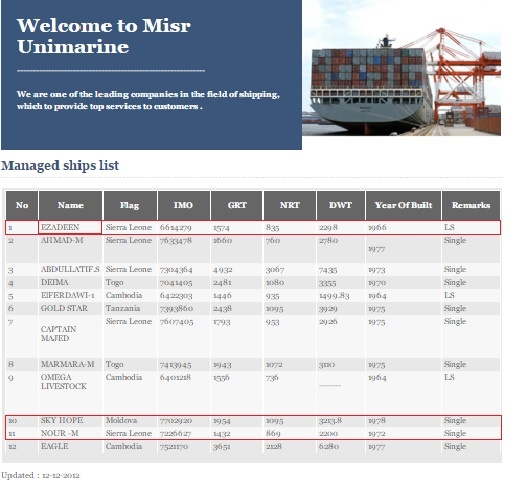

Abdullah Allouf is also director of Misr Unimarine, an Egyptian company. Misr Unimarine is another safety management company. On its website, we found the “Ezadeen” and the “Nour M”, which was seized in Greece on November 8, 2013 after the authorities found onboard 55 containers filled with ammunition. The “Nour M” was sailing towards Libya. The report by the panel of experts on Libya (sent to the president of the UN Security Council in February 2014) suspects that the ammunitions were destined to criminal organizations or terrorists.

We reached Abdallah Allouf for comments. He told us that the management contracts concerning the “Ezadeen” and the “Nour M” were signed through Uni-Marine Management Co. He didn’t mention Misr Unimarine. He told us that his role is to ensure that ships are in conformity with international safety rules, but that the management contracts he signs have no bearings on what cargoes the ships transport or their itineraries. Allouf told us he hasn’t entered into business deals with Youssef Mohammad Lebbadi, whom he says is only an acquaintance. But he said Lebbadi was the owner of the “Ezadeen”.

Allouf didn’t tell us that he also is director of three Panamanian companies. Through Uni-Marine Management Co and one of his Panamanian companies, Crest Shipping & Trading SA, Allouf owns the Sky Hope, a cargo ship flagged in Sierra Leone that was banned from entering European waters in June 2014 because it had been detained multiple times by port authorities of various European countries.

It’s not the only one.

The “Georgiana H”, flagged in Togo, was banned from entering European waters in July 2015 because of multiple detentions. The “Georgiana H” belongs to Johar Shipping, which is owned by another Syrian national, Hasan Johar, 35 years old. The Johar are a big family present in Syria, Romania, and in the UK.

In Constanza, we find the local branch of a company that delivered the safety certificate to the Georgiana H: Bia Shipping Co Ltd, created in 2010 in the Marshall Islands, an official partner of Johar Shipping. Hasan Johar is behind Bia Shipping as well, as he confirmed to us over the phone: “I’m not the owner of Bia Shipping, but I can be considered as such. I have the power to sign papers in its name”.

In a maritime database, we found a company called Bia Shipping Company Srl. But in Romania, where it’s supposed to be based, we found no trace of the company.

Next to the “Georgiana H” being banned, the Johar own four ships that violated European Union sanctions against trade with Crimea imposed in 2014. The Johar operate a shipping network that has ties to illegal and illicit activities.

Hasan Johar owns another company based in Constanza, Shnar Shipping Srl, together with another three Syrian nationals: Adnan Hassan, Ferhad Hassan and Abdul Rahman Hassan. Shnar Shipping Srl and Johar Shipping share the same address in Constanza. Abdul Rahman Hassan, 53, was arrested in 2014 in Constanta for smuggling 40,440 cigarettes from Turkey to Romania while he was the captain of the “Rania H”, a cargo ship owned by Johar Shipping since September 2014. The “Rania H” is operated by Bia Shipping.

Abdul Rahman Hasan was convicted, in October 2015, to three years and eight months in prison. According to the Prosecutor of Constanza, next to the illegal cigarette smuggling, Abdul Rahman Hassan was also convicted for human trafficking after he facilitated the illegal entry of two Syrian Kurds into Romania. The “Rania H” is still part of the fleet of Johar Shipping.

SMUGGLING INC.

From what we were able to determine from using social networks, the Johar, the Hassan and Saleh Emad have friends in common. They live and do business in Galati, Constanza, Tartous, Latakia, Lebanon, Egypt, and sometimes, Turkey. The Johar are very well connected in the shipping world. They are also connected to the “Blue Sky M”.

On 26 September 2014, the “Blue Sky M” was docked in the port of Constanza. Adrian Mihalcioiu, an inspector for the International Transport Workers’ Federation, was onboard the ship to check the complaint of two Indian cadets that had been sailing on the “Blue Sky M” for six months. In the course of his investigation, he found out that the captain of the “Blue Sky M” was a Syrian national. His name was Abdul Osaili. According to our Italian sources, it is conceivable that Osaili has been involved in other illegal smuggling operations using the “Blue Sky M”.

Abdul Osaili was probably not onboard the “Blue Sky M”. for the migrant smuggling operation of December 2014. The Italian authorities have no record of him, and he wasn’t arrested or questioned by the police.

We found the trace of Abdul Osaili in another ship purchase, which also took place in Turkey: the “Azra S”.

Until June 2014, the “Azra S” belonged to Khaled Jaohar, a family member of Hasan Johar’s. It then became the property – at least on paper – of Info Market Srl. We know this company: it provided services to Saleh Emad for the “Blue Sky M” and other ships he owned. At the beginning of January 2015, Abdul Osaili was captain onboard the “Azra S” when the ship arrived in the port of Constanta.

Three people we talked to over the course of our investigation told us that Osaili bought the “Azra S” from the Johar after he had sold the “Blue Sky M”. We don’t know if he financed the “Azra S” with the product of the sale from the “Blue Sky M” – 400,000 USD, according to a Romanian source.

The Johar can also be connected to arms smugglers.

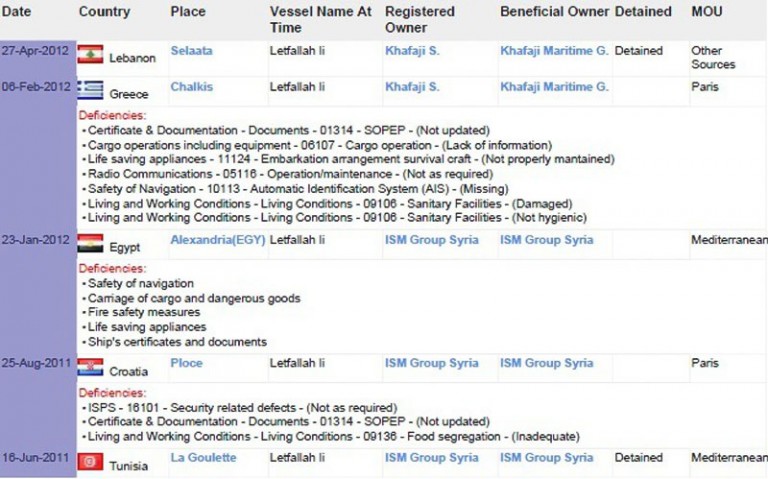

Another Johar, Ahmad, owned a cargo ship called “Letfallah I”I from 2010 to 2011, through a company called Letfallah for Navigation. In January 2012, Mohammad Khafaji, a Syrian citizen, bought the “Letfallah II”. In April 2012, the Lebanese navy intercepted the ship and found three containers filled with ammunition onboard. The ship came from Libya. The ammunition was probably destined to fuel the Syrian conflict. In August 2015, the Lebanese Military Court convicted Khafaji of weapons trafficking – in abstentia.

Khafaji also owned the “Alexandretta”. When the Greek authorities inspected this cargo ship in the port of Volos in February 2013, they found “three containers containing more than 1,700 hunting rifles and 1 million hunting cartridges, as well as 2,500 blank-firing pistols and 500,000 rounds of related ammunition”, according to a report compiled by a panel of experts appointed by the UN Security Council.

The “Alexandretta” came from Turkey. The Greek authorities seized the shipment but the ship was released. According to the report by the panel of experts, “the companies and some people working for them are complicit in weapons trafficking activity”.

The “Leftallah II” is not the only connection Khafaji shares with the Johar: in June 2015, Khafaji bought the “Basel S5”, a cargo ship flagged to Palau, from Johar Shipping. At the time of the sale, the ship was in Turkey.

The “Letfallah II” was sold to Khafaji in January 2012 by a Syrian company called the ISM Group Ltd, specialized in maritime services. Two of the ships owned by the ISM Group Ltd are listed in a report about arms trafficking, published in 2013 by the US think tank the Centre for Advanced Defense Studies, C4ADS. The “Mega Star” and the “Hiba K” renamed the “Rasha D” in October 2015.

The ISM Group Ltd was also the previous owner of the “Nour M”. the ship onboard which Greek authorities found ammunition in 2013. The ISM Group Ltd sold it to its current owner in 2007. Another business of the ISM Group Ltd is to operate the registration of ships for the flag of Sierra Leone, from Tartous. The “Nour M” and the “Letfallah II” were both flagged to Sierra Leone.

The “Haddad 1”, which we linked to Rani Sarkas, was shortly under the ISM Group’s ownership, from September 2014 to February 2015. In November 2014, the “Haddad 1” was detained by Spanish authorities in the port of Malaga. They let the ship go to Egypt to fix the deficiencies they had signaled for the ship. The Haddad 1” never made it to Egypt. Instead, it sailed to Turkey where it remained until it was sold to its current owner, whose identity we were unable to confirm.

OPEN INVESTIGATIONS

In Greece, five of the seven Syrian and Afghan nationals who had been arrested in July as members of the crew of the “Baris” were found guilty of people smuggling and were sentenced to 25 years in jail. Each of them was fined 200,000 EUR. The other two men were found innocent. The “Baris”, flagged in Kiribati, had left from Mersin on EUR 5,000 and EUR 7,000 for this trip, which only lasted for two weeks.

Human trafficking is a crime in many countries, including in Syria, where a 2010 law aims to prohibit and prevent it. On the other hand, human smuggling – when migrants and refugees voluntarily use smugglers’ services to bypass border controls, such as was the case onboard the cargo ships we investigated – is not necessarily the doing of the same groups.

It remains to be seen whether the perpetrators of the human smuggling made onboard cargo ships will be caught. From what we have gathered over the course of our investigation, the countries have so far failed to collaborate in the judiciary sector. Investigations are sliced up. Information-sharing hasn’t yet become the norm. The rogatory commissions, sent by prosecutors to other countries to ask for information, are slow and often unsatisfactory. On 22 February, Europol launched a new taskforce to help countries investigate human smuggling. Yet, the issue of human smuggling still remains a low priority in many countries.

Editor Note: a special Thanks for the help from: Investiagtivedashboard.org and Organized Crine & Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).