Wooden swords, toy rifles, and black headbands bearing the words “Cubs of the Islamic State” are some of the items sold at the Ibn Taymiyyah grocery store in the village of Qashlat, in the eastern Aleppo, now under the control of the Islamic state (IL), formerly ISIS.

The store opened after IS seized the village in late July 2014. It sells Harisseh(TN: Middle Eastern dessert) and soft drinks, as well as black shirts and loose trousers, the kind worn by members of Islamist groups in emulation of the “pious ancestors.” (The first few generations of Muslims)

On the opposite side of the shop lies a primary school. The wall still bears slogans of the ruling Arab Baath Socialist Party : The word “freedom” spray-painted in green. The word appears as though it was sprayed with trembling hands, reminiscent of a time dissidents would write their slogans in secret. On top of the word “freedom,” someone else wrote “Islamic State” using black spray paint.

This was one of the first things both investigative reporters spotted as they headed to al-Qashlat on January 3, 2015.

In line with these contradictory slogans, the students of this village and nearby ones follow different educational curricula, depending on the faction that dominates in their respective areas. Most of the curricula contain exclusionary ideas that urge “jihad and sacrifice for the sake of God,” at the expense of science and math, as the authors of the investigation have documented.

The IS-improvised courses conflict with the state-run unified curriculum – regardless of its pros and cons – that was in use when the Syrian regime was still in control of the entire territory of Syria, before the revolution erupted in the spring of 2011. The first pages in the books that have been cancelled had staple words that never changed regardless of any amendments to the curriculum: The Syrian Arab Republic and the Ministry of Education. The ministry relied on expert committees, which produced courses based on studies and priorities related to the national and religious identities and behaviors desired for children according to the criteria of the authorities.

In parallel with the multiplicity and contradiction of these curricula, thousands of students have dropped out due to forced displacement, disintegration of families, destitution, and the collapse of the educational system as hundreds of schools were destroyed amid a shortage of teachers.

The British organization Save the Children estimates the number of children now outside the education system at 3 million. This number represents more than half of all Syrian children, compared to the last figure provided by the Syrian Education Ministry in 2012, which counted 5.5 million Syrian students in all stages of study. However, Save the Children’s figures, published on September 18, 2014, ranked Syria second on the list of states that lack enrollment among school-age children worldwide.

What is worse than dropping out is that some students have joined informal schools that teach different curricula tailored to the whims of the rival factions. These students are at risk of ignorance, extremism, and effacement of their national identity, not to mention the loss of their future. For one thing, their education is over at the end of the stage set by respective factions. And the degrees they issue are unrecognized by universities.

All the students whom the authors met appeared confused without a clear vision or ability to answer questions quickly.

Fragments of a state

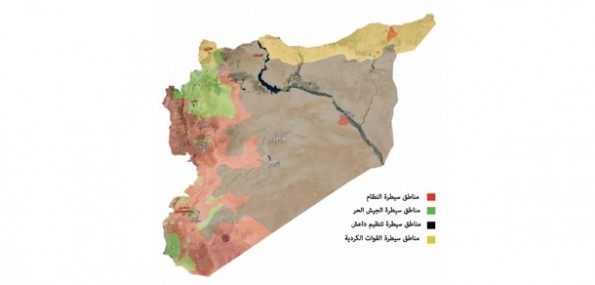

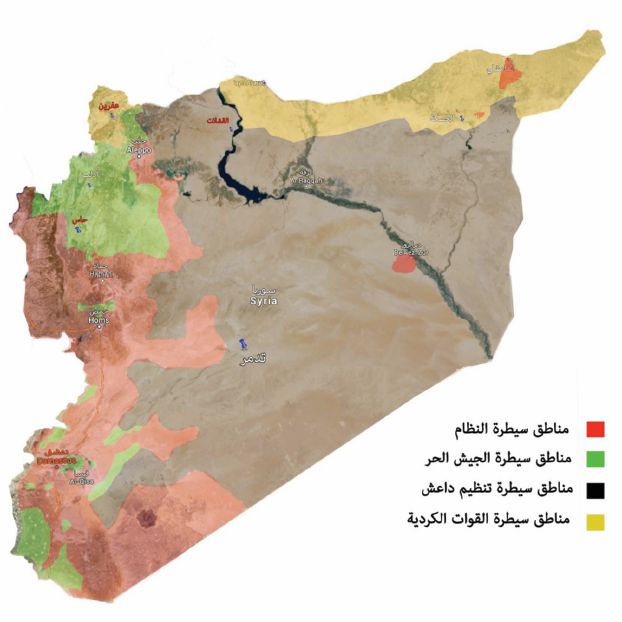

(Map showings the areas controlled by armed factions in Syria)

Red= Regime control

Green = Free Syrian Army

Black = IS

Yellow = Kurdish control

Syria is currently subject to several divisions. They are not necessarily separated by demarcations, but are under the control of different armed factions, many of which have defined the form and religious identity of the area they control in accordance to their respective vision.

Both reporters have chosen four regions controlled by different armed groups. There, they distributed a one-question survey addressed to students in basic education there. The question said: “What is the name of your homeland?”

The answer came as follows:

| Student’s age | Answer (name of homeland) | Class | Area | Armed group in control |

| 9 | Rojava | Fourth grade | City of Afrin | Kurdish Protection Units |

| 9 | Syrian Arab Republic | Fourth grade | Town of Has | Syrian opposition |

| 9 | Syrian Arab Republic + Baath Party slogans and Bashar al-Assad as head of state | Fourth grade | Damascus | Syrian regime |

| 9 | Islamic Caliphate State | Fourth grade | Village of al-Qashlat – Eastern Aleppo countryside | IS |

Trip to the village

We travelled to Qashlat by motorcycle. For one thing, motorcycles are rarely searched at IS checkpoints, and their passengers do not raise any suspicion.

Both reporters had arranged to meet with a family in Qashlat, a village with a population of 3,000. The family expressed its willingness to cooperate on the condition that its identity is kept secret. The family feared retribution from IS. The meeting seemed easy to arrange, thanks to the prior acquaintance between one of the authors and that family.

Moaz has extremist tendencies and Ayman is under-schooled

The authors of the report met with Umm Muhammad – mother of two boys, Moaz in 6th grade and Ayman in 1st grade. Umm Muhammad says that her son Moaz studied under the regime’s curriculum, before the non-Islamist Syrian opposition removed the course dealing with nationalism and everything related to the Syrian regime. She did not notice that the curriculum altered her son’s behavior or thinking. However, things did change after IS took over, she says, and now, her son wants to be a mujahid rather than a doctor.

Moaz no longer draws Syria’s flag or plays football in the neighborhood. His favorite toys are rifles and swords. “I saw him once shout at his friend while playing: I will punish you by beheading you,” says Umm Muhammad, in reference to the Sharia-inspired corporal punishment imposed by Islamic groups.

Umm Muhammad speaks with regret as she glances at Ayman, her younger son: “I would prefer for Ayman to leave school and sit at home until the situation returns to normal, than for him to act like his brother Moaz.”

The Caliphate State

“The Islamic Caliphate State,” Moaz answered when asked about the name of his homeland, and continued with a quote from IS leader “Caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Moaz does not recognize Syria and says: “Democracy is blatant apostasy, judgment belongs to Allah.”

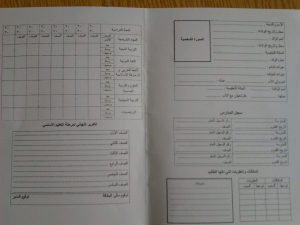

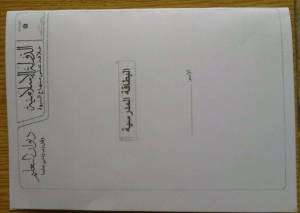

The authors of the report were able to enter one of the printing presses belonging to IS. They took pictures of the school card showing the names of the courses used in the basic curriculum. The press was not modern. It contained printers of various sizes, originally belonging to the Technical and Municipal Services Department that IS had seized.

(Table showing the main differences between the Syrian regime curriculum and the IS curriculum)

| The Syrian regime curriculum | Islamic State curriculum |

| Math | Pythagorean theorem removed |

| Arabic | Islamic and Arabic calligraphy added |

| Religious education | Jihadi education added, containing lessons encouraging jihad and related fatwas by medieval scholar Ibn Taymiyyah |

| Natural sciences | Unchanged. Health education added, containing disease awareness lessons |

| Physics and chemistry | Abolished based on fatwas prohibiting them for interfering in “divine matters” |

| Art and music | Abolished based on fatwas prohibiting drawing and music |

| Social science and Civic Education | Abolished |

(Photos of school card)

Using video, the authors filmed an example of the curriculum in use, for which educators received training during a “Sharia course” with the Diwan of Education of IS. The curriculum is essentially based on

interpretations and fatwas of Ibn Taymiyyah, the primary authority for the radical group’s theorists.

Both reporters have obtained voice recordings of the slogans IS teaches to its students each day before classes start. The slogans replace those of the Baath Party and the Baath Vanguard Organization previously used in government schools.

البطاقة المدرسية

One of the members of IS chants instructing his students to repeat after him the following phrases:

“Our youths come to the lofty places, let’s go climb the high mountains

Let the stubborn arrogant fall let the stubborn arrogant fall

Tomorrow we shall rule by the law of our Lord, tomorrow the unbelieving Taghut shall fall.

Allah is Great!”

(Supplied with an audio clip of the pupils in a class being taught the slogans)

It was completely different from the slogans of the Baath Vanguards Organization and the Baath Party that the pupils used to chant.

“One Arab nation with an eternal message, our goals: Unity, Freedom, Socialism.

My Vanguards comrade, be prepared to build and defend the Arab socialist society,

Arab, Baath ”.

Rojava: The state of Western Kurdistan

The reporters’ next destination was the Afrin canton, 90 km from Qashlat. There, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) run the territory it has declared as the state of Rojava, which translates to Western Kurdistan. It was similar to a large extent to what happened in government-schools, in terms of the formalities: portraits of Abdullah Ocalan, leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party – incarcerated since February 1999 in the Turkish island of Imrali in the Sea of Marmara – and the red flag of the party along with slogans written on the walls in Kurdish.” These symbols have replaced the portrait of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his party’s slogans, as the YPG in control of the cantons of Rojava are the Syrian branch of the PKK.

Receiving an official permission from the Asayish, the local security authorities in the Afrin canton in the Aleppo countryside, was impossible for security reasons. Hence, it was not possible to move easily. The second-best option was to choose a random sample.

We chose a 4th grade student we met as he left his school. We pretended to ask about an address, then we asked him about the name of his country, and he replied: “Rojava.”

The school teaches its curriculum in the Kurdish language, which is not used by official Syrian schools or schools in the areas controlled by Islamist groups or opposition groups. The school also removed from its curriculum all phrases containing the words “Syrian Arab Republic,” replacing the words with “Rojava.” It also abolished civic and religious education courses that followed the Syrian government curriculum.

In mid-June 2015, the first conference for training in a democratic society held at the Celadet Bedir Khan Academy in the city of Qamishli, in north-eastern Syria, approved a series of decisions concerning the education system. The decisions proclaimed that the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party is Abdullah Ocalan and that he is a symbol representing all communities in Rojava and the Middle East. It was also decided that education in the schools of Rojava will draw from the ideas of Abdullah Ocalan.

The conference approved the courses that would be taught in the schools of Rojava in primary education.

Stage 1

Grammar and literature of the mother tongue; geography; culture; ethics; the environment; history of Kurdistan, the region, and the world; women’s issues; math; sciences; health; language of a people from the region; foreign language; arts; music; painting; folklore; drama; and sports).

Stage 2

(Kurdish, social sciences, culture, history, monotheistic religions, math, sciences, sports, painting, music, and visual studies—film/theater).

The ‘two’ Syrian Arab Republics

On the morning of January 25, the authors travelled to the Has region in southern Idlib, an area controlled by the Syrian opposition.

In this area, the “nationalism” course was abolished along with everything related to the Syrian regime in the curriculum.

Classrooms have been moved from school buildings to shelters because of constant shelling. “The stoppage of education means the clock is moving backwards indefinitely,” says Youssef, a teacher who escorted us to one of the schools here.

There are eight classes for different ages. The ceiling is two meters high from the ground. There are no windows for air or sunshine to enter. Health standards are not as important as safety from barrel bombs and shells. Entering the school requires going through a slope that has over ten steps, some of which are broken and slippery. But for the authors of this report, they were a picnic compared to the rugged road they had to travel through from Aazaz via al-Atarib, Ram Hamdan, al-Maara, to Has.

We spoke to Aboud, a 4th grade student with average grades, as Youssef described him.

“What is the name of your homeland?” Aboud replies: “The Syrian Arab Republic.”

What else? “I don’t know.”

“Do you want to share anything else you learned about Syria, an organization you belong to, or something of the sort?”

He shakes his head, smiling. “No.”

We asked the same question to two other students, but their answers were similar. Youssef explains the situation by saying that most educational institutions have agreed to keep education neutral. “Educational value is the goal and having degrees that are recognized is the objective, and this can only be achieved through concessions from both sides. Everyone agrees about this.”

Our questions were not yet over. For this reason, the authors arranged another meeting in the Aleppo countryside on January 26 with Dr. Yunus. Yunus had sent his wife and kids to Damascus, so that the children could enroll to study the “officially recognized curricula,” in reference to the program run by the Syrian regime’s Ministry of Education.

The visit took place during the weekend, and the children were back from the capital. Ahmad – a 4th grader too – has a similar answer: My homeland is the “Syrian Arab Republic.” However, he adds without being solicited the slogans of the Arab Baath Socialist Party: “One Arab nation with an eternal message.” He did not separate the name of the homeland and the slogans, as though they were one and the same, before he hastened to add: “Under the leadership of President Bashar al-Assad”, who succeeded his late father as head of state in 2000.

IS has the most influence on the minds of the pupils

Abu Nizar is an elderly teacher due to retire next year. Abu Nizar – who declined to share his real name for security reasons – is one of the teachers who was hired by the Ministry of Education to amend the curricula in Damascus, beginning in the academic year 2007-2008. The new curriculum was trialed in a number of schools in 2008-2009, before it was adopted and circulated to all grades and schools in 2010-2011.

Abu Nizar’s work as a teacher underwent three stages in the eastern Aleppo countryside: first under the Syrian regime, then under control of the Syrian opposition control, and finally, under the control of IS. In his home library, Abu Nizar has booklets distributed by IS during a “Sharia seminar” containing guidelines for the teachers.

Abu Nizar goes inside for a few minutes then returns with a small box. He takes out a dusty notebook and a plastic green folder with the words “Preparation book” on the cover. The book contains notes recorded by the teacher about his daily classes and signed by the school director.

Abu Nizar speaks with regret and sighs. “It was a boring daily routine, but today I understand its value. The current chaos has made me believe that all details related to teaching methods, even the boring ones, were important.”

He continues: “Under the regime, specifically in recent years, students lost their concentration and focus in general because of the new complicated curricula. The Ministry of Education held training courses for teachers to make it easier to deliver the learning outcomes to the students.”

As for the national identity used by the regime, it was nationalistic and sought to promote the goals of the ruling Baath Party through the ideas that permeate the civic education course. The regime have a small margin for religious education through two sessions a week, unlike IS, which made religious education the core of its curriculum. Religious education has no significance when it comes to university admission, so students under regime areas usually ignored it.

He recalled that the military education course along with the shooting training, which the regime started at the 7th grade in schools, was abolished by a decree issued in May 2003. The phenomenon was dubbed “militarization of education” at the time, with pupils donning military fatigues, including both boys and girls. The trainers had absolute power and could discipline students in any way they wanted.

After the opposition took over, civic education was abolished along with everything associated to the Baath Party and the regime. The main focus shifted to pure education, without imposing a different national or religious identity.

One reason was that the opposition was fragmented and divided, and did not have a unified educational curriculum or national identity. For example, those in charge of the Interim Ministry of Education disputed over the slogan “the Syrian Republic” and the “Syrian Arab Republic,” with opposition from Kurdish figures, who ultimately developed their own curriculum recognizing a Kurdish autonomy and bypassing the notion of a Syrian Arab Republic with one united territory.

After it took over in late January 2014, IS abolished the national and religious identities used in official curricula and launched its own versions, first as an “Islamic state” then as a “Caliphate.” This identity has no limitations, because it is constantly expanding. IS showed exceptional ability in influencing young students by manipulating their religious sentiment and inducing them by using money, according to Abu Nizar. IS thus “succeeded and surpassed both the regime and the opposition in indoctrinating [students] especially in the age group 6-13 years with its ideas and identity.”

Upbringing – that is child behavior – is so important that it was put ahead of education in the ministry’s definition. Syrian teachers would thus first define the function of the entity in which they were enrolled, pointing out to them the importance of discipline and good behavior in the early years of basic education.

Government recognition only

Despite efforts by the factions controlling the Syrian territory to impose their curriculum, international recognition of the degrees they grant is only confined to Syrian government schools. For this reason, IS opened its own medical school in the city of Raqqa with its graduates going to work in areas under the group’s control. Several universities opened in areas controlled by the opposition, such as the Umayyah University and the Free Syrian University, but they failed to obtain international recognition of their degrees. This did not help them reflect enough confidence to attract students to enroll. Meanwhile, the Kurdish forces did not open universities that recognize degrees issued by their schools until the moment of writing this investigation.

Minister of Education declines to comment

On March 23, 2015, the authors of this report went to the Interim Ministry of Education in the Turkish city of Gaziantep to obtain a comment from the Interim Minister of Education Dr. Ammar Barq. However, Barq declined to make any comment. Both journalists repeated their attempt on March 26, 2015 by contacting his office director at 10:30 a.m. An employee answered the phone and asked them to call again half an hour later. The reporters did, but the employee asked them to call again, later. Both reporters called a third time at 11:23 a.m. and were transferred to the minister’s assistant, who told them Dr. Barq declines to give any statement on the issue.

Ideas presented in “rigid boxes” in curricula

Both reporters shared samples of the children’s answers and the curricula with Aya Muhanna, psychologist and expert on Syrian issues. Muhanna said education in Syria follows a “rigid pattern”. This, she says, is contrary to curricula in developed nations, which are modified every four, seven, or twelve years, with a trial period during which specialists measure their impact.

In the climate of war in Syria, children discover things prematurely, and their minds are not equipped to deal with them. This poses a grave risk to the children’s intellectual development, according to Muhanna. This weakness among children is exploited by the political and military factions wishing to indoctrinate them politically, religiously, and philosophically.

This investigative report was completed with support from Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) www.arij.net.