Al-Iqtisadi – His entire life’s work vanished in minutes, but not from the bombings and battles.

Upon returning to Saqba, east of Damascus, Abu Ghayyath and his family were happy to find that their house was not damaged by the battles. But he discovered that the stones of his house had collapsed through fraud: someone else came up with documents proving ownership of the house.

Abu Ghayyath and surviving members of his family are now sleeping on one of Damascus’s sidewalks without a roof over their heads. He may be one of thousands of displaced refugees who have been twice victimized and twice displaced: The first time by the war. The second time by falling prey to war merchants exploiting their absence to sell their property through fraud.

This investigation documents the labyrinths of fraud and impostors that have spread since the eruption of the Syrian crisis in 2011 by war merchants and in collusion with civil servants and lawyers exploiting gaps in the laws related to power of attorney (POA), real estate ownership, and the penal code. The loose Criminal Penal Code, which is supposed to deter fraud, exacerbates the problem, in which one of the affected parties would lose their rights during a lengthy legal process in courts which could take up to 10 years.

These reporters paid repeated visits to the notary departments and tracked down the steps taken to issue forged POAs. They also documented the methods of fraud and gaps exploited to complete this process.

The deceased are also victims of fraud. Tawfiq Almadar from Damascus had his property stolen through a POA forged by a network in his name two years after his death in 2011.

Fraud apparently rotates with the cycle of the crisis in Syria, grinding at the rights of citizens fearing the loss of their homes at the stamp of a forger.

Chaos has been a companion in all circumstances as the war continues. One Syrian family is displaced every 60 seconds — or 9,500 civilians per day — according to a report by the UN’s Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC).

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), meanwhile, announced that 10 million people have fled their homes, with 6.5 million internally displaced and 3 million across borders, according to a report published on August 25, 2014. None of these people can secure their property from the phantom of fraud through a POA forgery carrying the name of the owner or impersonating the owner with a counterfeit identity card.

Organized networks

In the absence of official statistics on property fraud, these reporters documented nine cases during six months of investigation, including six POA’s, two contracts, and one property embezzlement case. One case condemns several lawyers. All officials interviewed acknowledged fraud. These reporters managed to look at official records and documented more than 2,300 lawsuits filed by Syrians requesting their property ownership deeds, which were either forged or lost in the war. Another (attached) chart includes 22 court rulings against convicted frauds during a one-year period according to documents collected from real estate registries between August 15, 2013 and August 30, 2014.

Furthermore, these reporters tracked a forgery process to issue a POA for a person abroad after clinching agreement with the wrong-doer. Indeed, the process went smoothly until the end and could have been officially stamped and endorsed.

“Organized networks with expertise in the law are behind fraud cases and they are not isolated,” according to Tayseer al-Smadi, aid to the Syrian justice minister. He likens forgery cases to tearing up the Syrian Constitution, noting that “attacking the first constitutes an attack on the latter because individual ownership is safeguarded under Article 15 of the father of all laws (constitution).” But he adds that “justice will not stand idle and has taken tough measures to eradicate fraud.”

According to Article 443 of the Syrian Penal Code, fraud is defined as “an act distorting truth, facts, and data sought to be proven in a contested deed or writing, which could cause material, moral, or social harm.”

Official numbers

Real estate expert Dr. Ammar Yousef is a member of several real estate committees, including one that was formed in 2013 under Decree 1244 to reconsider existing property laws and draft unified legislation following a rise in fraud and cases of illegal takeover. Yousef was not reluctant to share high numbers of fraud cases with these reporters. He estimated 30,000 cases in Damascus and its countryside (Rif Dimashq), the highest in Syria, followed by Aleppo governorate with 8,000 cases and Homs with 6,000 cases. The remaining 11 governorates had a combined total of 5,000 incidents in the past three years.

Court of Cassation Judge Badie Hazzaa, who heads the same committee and was interviewed twice by these reporters, disagreed with Yousef’s estimates, saying there were 11,000 fraud cases in Damascus and its security-heated countryside since 2011. This estimate is further reduced by Mohammad Yassin Qazzaz, 7th district attorney in Damascus , who talked about 5,000 cases in Damascus and its countryside, including 50 percent registered before the eruption of the conflict.

Qazzaz’s estimate is closely backed by a senior official at the Palace of Justice, who estimated 20 cases per day in 2014: nearly 7,300 cases.

According to lawyer Dalal Hashem, pursuing a fraud case in court costs an average of 150,000 Syrian pounds ($885). Therefore, the cost of pursuing 49,000 court cases amounts to an average of SYP 735 million ($43 million).

Making the POA

With the forced displacement or migration of Syrians due to the war, thousands line up outside the notary offices for POAs allowing friends or relatives to act on behalf of those abroad or displaced to handle their respective property. But actually, numerous cases were nothing more than property theft through fraud and identity theft.

Every morning, dozens of petition writers gather outside the Palace of Justice to draft POAs, which include information on the real estate and names of the two parties (grantor and agent) in return for SYP 200 ($1.30). The draft POA is then sent to the notary for registration at a cost of SYP 1,050 (approximately $7.00) before the two sides obtain the official and final stamp in a process that takes no more than 10 minutes. The first copy of the POA is retained by the agent and the notary keeps the second copy by gluing it in his registry book.

According to Article 665 of the Syrian Civil Law, a power of attorney is defined as “a contract in which the agent is committed to handling the legal matters of the grantor.” The POA related to selling property is divided into two: “General,” which authorizes the agent to handle all the grantor’s affairs, including the sale of his property, and “special” for the sale of property. There is absolutely no difference between the general and special POA, whether in terms of the issuing or forgery process, other than the latter requires a real estate deed during the sale, which comes under Article 86 of the Syrian Real Estate Registry Law.

Four methods of forgery

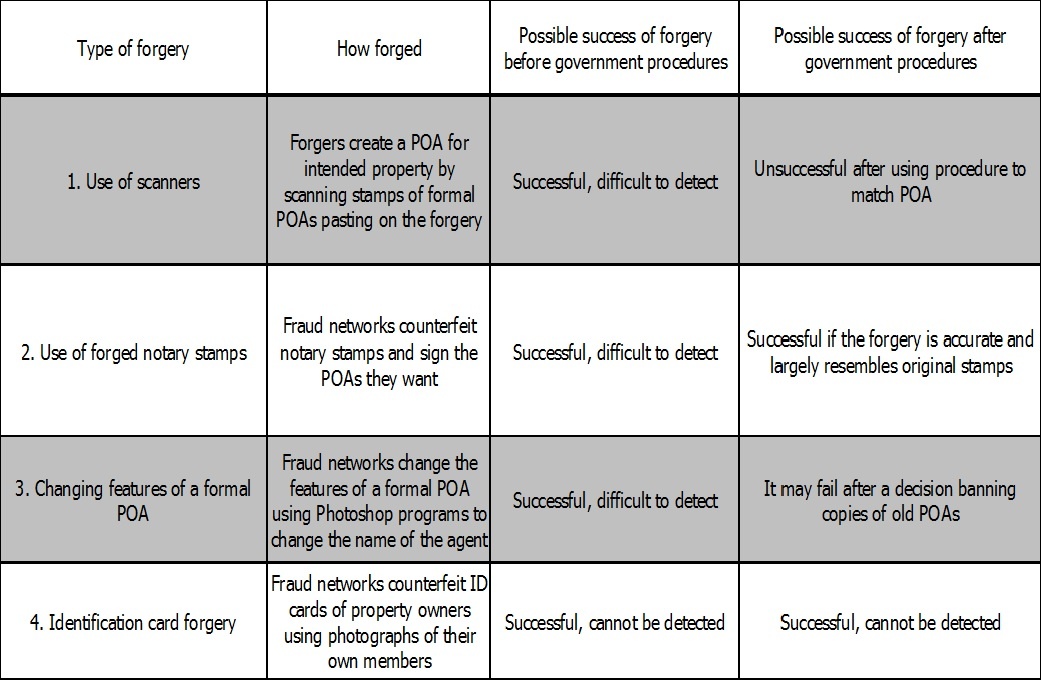

These reporters looked at the notary’s registries in Damascus. In reviewing most of the records, they monitored the steps taken to forge POAs. The process began by confirming that the intended property is vacant and its owners are displaced or traveling. It followed by pulling out the intended property record and including its information on the POA document. These reporters, in cooperation with a specialized judge, tracked four types of forgery as follows:

ID card forgery cannot be detected

Muhannad Rajula is a victim of identity theft. A fraud network devoured his property after it managed to counterfeit his ID card and add a photograph of a member of the same network and handed another element power of attorney over his house.

The networks obtain a copy of the ID of the targeted property owner by virtue of knowing the person or from the civil registry without his knowledge.

Alaa Tinawi, the 5th district attorney in Damascus, said that Muhannad is not alone. This method, he says, “was the most commonly used to forge POAs.” He acknowledges that inquiry clerks have no means of detecting them.

Tinawi says the only way to stop this is by using electronic archiving and linking ID cards to specific numbers and providing the notaries with the proper detection devices. Agheed al-Jallad, director of the temporary registry, agrees that “electronic automation” system is the only solution.

The threat caused by counterfeit ID cards is not met with stringent penalties. Articles 452 and 454 of the Penal Code consider it a misdemeanor with a prison penalty ranging from two months to two years. This is because the forgery process took place without coordination of government parties, but with a special device used by counterfeit mafias.

Loss of property deeds serves forgers

People losing their property deeds is the worst disaster in the service of fraud networks because retrieving them is extremely difficult, especially if the property is in a security-tense area.

During a period of six months and on a daily basis these reporters tracked and documented 2,317 people who lost their property deeds in most Syrian governorates — except in the east because of difficulty in reaching the area’s real estate directorates.

Lawyers, judges implicated in networks

According to the Justice Ministry, no fraud network, no matter how professional and organized, could complete its task without the help of lawyers, judges, or civil servants. If it is not collusion, it is the negligence of judges, at best. The ministry issued Circular 67 to judges saying that Judicial Inspection Report 69 of 2013 found some judges to have committed “serious professional mistakes,” especially in verifying identities.

This negligence is not the essence of the problem, according to Cassation Court Judge Hazzaa and head of the Real Estate Commission, who said that several judges were assigned to hear the trials of other judges implicated in endorsing forged POAs. He revealed that six judges are currently under investigation in Damascus alone and talked about the arrests of several cells. In one case, a judge and five lawyers were implicated. Hazzaa showed these reporters one of these decisions, but refused to reveal the names to preserve the confidentiality and immunity of the judicial corps.

Fifth district attorney Tinawi confirmed that several notaries have been under investigation for months on suspicion of collusion with fraud networks, adding that a judge’s penalty ranges between a warning, disbarment and prosecution. But he stressed the need to differentiate between a judge’s negligence and implication in a crime.

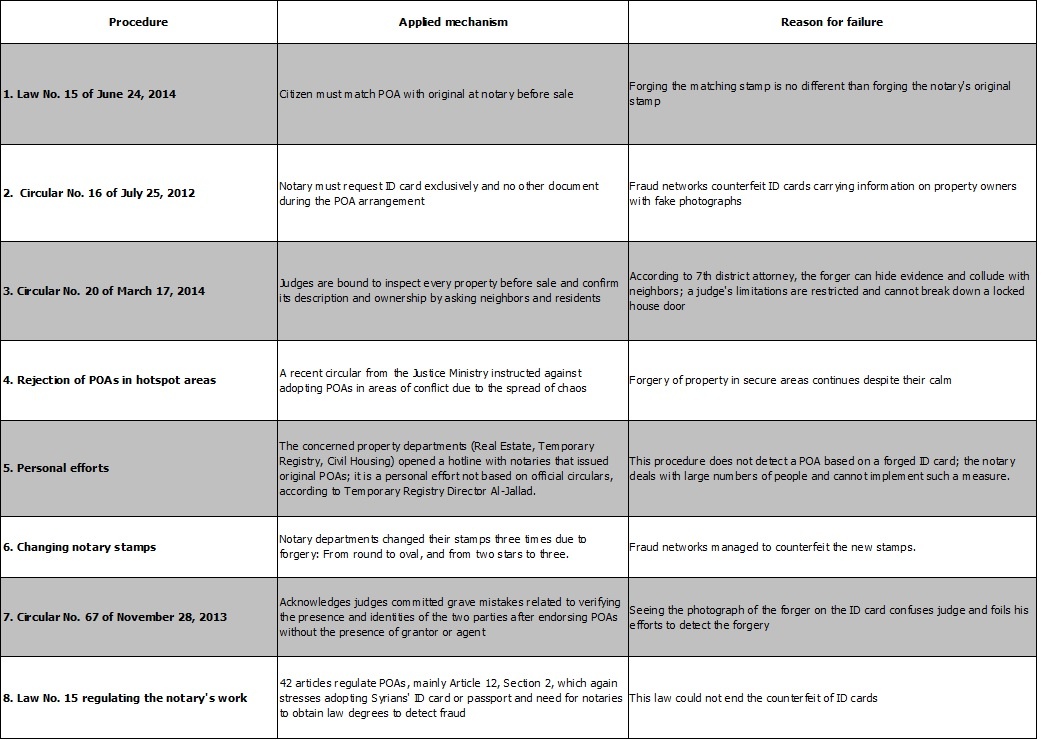

Useless procedures

This investigation’s reporters accompanied eight individuals seeking to issue POAs over a six-month period to monitor and document the integrity of the procedures and identify the relevant gaps. Eight legal and procedural gaps were documented which could be used to commit the crime of POA fraud. Judge Qazzaz expected deterring procedures would reduce fraud cases by 30% to 40% and complained at the lack of final solutions to end fraud during this crisis.

Most of the above procedures appear to have failed due to the way ID cards are forged to obtain POAs.

Loose criminal penalties

Fraud operations will continue heavily due to difficulty in stopping them and because the penalty for proven fraud is considered loose, according to Judge Qazzaz, who revealed that the judiciary intends to establish a committee to reconsider the Penal Code, which he said contains numerous mistakes for fraud. According to Article 448, forging personal documents that do not carry an official stamp in transfer of ownership, such as contracts of sales, is considered a crime carrying a penalty of three to 15 years in prison because it was carried out in coordination with government departments. But Articles 452 and 454 of the same law regards the forging of an ID card as a misdemeanor with a penalty of two months to two years only, although counterfeiting ID cards is the most serious and undetectable method to obtain POAs. It is a misdemeanor because the mafias operate without coordinating with government departments through a special device used to individually counterfeit the cards.

Qazzaz added that the judges handle all the cases on a minimum basis; if a defendant confessed to his crime and appealed for mercy and pardon, the judge would commute his sentence to almost a quarter under the related provisions of Articles 243, 244, and 245. Judges also use their own discretion, such as the nature of the crime and the amount and size of damage caused.

Labyrinth of retrieving property

These reporters accompanied Abu Ammar, a victim of fraud, on a journey to retrieve his house. The response was: “The buyer of the property proved his ownership at the Real Estate Registry and you have no right to the house.” Five people interviewed for this report failed to retrieve their property.

According to cases monitored, fraud networks are eager to sell property that they directly steal. This is where the war begins between the original property owner and buyer. Judge Qazzaz said: “The two have the right to the property if the buyer proved good intent; in other words, he had no knowledge of the fraud.” Confirming that the courts are hearing such cases, he added that if the property was sold under a POA alone, the original owner would retrieve it and the buyer would lose it. If the latter proves his ownership at the Real Estate Registry, the property becomes his right and the original owner loses it, although this standard adopted by the courts is not regarded as a final ruling in specifying ownership.

Abu Ammar wondered: “If fraud took place without my knowledge and the security services arrested the perpetrator, why don’t I get my house back?” He added: “It’s not my concern whether the buyer proves his ownership at the Real Estate Registry. This house is mine.”

Qazzaz acknowledged that “this way is not fair but it is the most logical.” He said that the courts try to pressure the forger to compensate the side that lost by detaining him for 90 days under Article 460 of the Court Procedural Code. If his term ends and proves he does not have the money, everything ends. This applies to “easier cases” which are rare because most lawsuits take years and come under the court’s discretion rather than a law determining the identity of a property owner.

Indefinite lawsuits

Some property fraud and takeover lawsuits take 10 to 15 years in the courts due to several factors, according to Judge Tinawi. This depends on the presence or absence of the defendant, whether the plaintiff pursues the case, and the time it takes to gather the documents and evidence from different places through correspondence between the civil court and the parties where fraud took place. Tinawi explains that “long court cases exist in most countries in the world due to procedures involved in collecting evidence. There are no statutes specifying duration of court trials; if the defendant appeared in court and the plaintiff pursued and completed collecting evidence, the case would take only a few days.”

In the meantime, the resident on the property, even if under suspicion, would remain in the property until the end of the trial.

Tinawi said that the judiciary cannot force anyone out of his property until the identity of the owner is verified for fear of libel, which constitutes 60% of all lawsuits filed. He added that the main reason for delays is the legal status of the property, the number of properties, the number of plaintiffs and defendants, the nature of the fraud, and degree of consequent damage.

Fraud today has become a fact that must be fought. Amending the relevant articles in the Penal Code has become urgent, according to lawyer Mohammad Manar Hamijo. He stressed the need to raise the fraud penalty to 15-20 years of hard labor, deeming POA fraud as a criminal offense, and criminalizing civil servants cooperating with the mafias in the Economic Penal Law because this crime affects the public sector.

On determining property ownership, Hamijo expected restoring property to its original owner and the state’s compensation to the buyer at half his losses, at least, if the criminal is unable to pay compensation. In the latter case, putting him in prison for 90 days is not enough; he must face severe penalties.

Meanwhile, Abu Ghayyath will continue to sleep on the sidewalks and parks of Damascus while Um Mohammad and her children live in a tent after returning to find that her house in Aleppo is now occupied by a man claiming ownership. So far, her daily journey between the courts and notary authorities to retrieve her house have borne no fruit.

This investigation was completed under the supervision of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, ARIJ: www.arij.net