Damascus,Nov 29,2015.

By Ziad Omar and Ahmed Abdallah

Alhayat– Beyond the known suffering of Syrians who are living under fire or migrating through rough seas in rundown boats, another more brutal and dangerous world exists, that of a black market in organ trafficking leading to a worst fate.

This report investigates the involvement of medical doctors in organ trafficking networks targeting Syrian victims. The networks begin in Syria and move across the borders to Lebanon, Egypt, and Turkey.

Others are also involved in the business, starting with fake security officials and ex-convicts and ending with pimps. This investigative report documents hitherto details on unknown cases involving organ traders who were arrested by the Syrian authorities.

In addition, the report reveals how hospitals and doctors continue to practice the business, benefiting a security breakdown since 2011. These gangs resort to a loophole in law number 3/2010 on combating human trafficking, as article three does not punish or incriminate the donor.

Complex networks

Among those revealed by the report are doctors, gunmen, women, a convicted pimp, and a fugitive wanted for “debauchery and organ trafficking”.

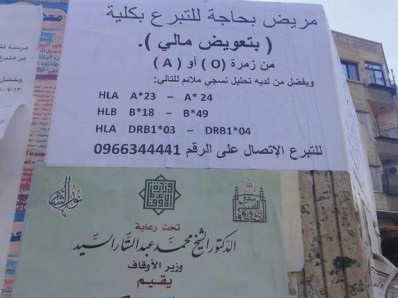

Members of these networks work in clinics and hospitals across most Syrian cities and regions. Some of them carry unlicensed guns, while others manage the e-marketing of human organs, as per in the following advert:

“For sale: Kidney of a 27 year-old male who needs the money to travel to Europe. Free of any viruses or genetic diseases. Currently residing in Turkey. For inquiries: send private message.”

Both reporters went undercover once posing as donors (sellers) and once as recipients (buyers). In both cases, they recorded conversations with the person behind the advert, who turned out to be a mediator for an organised network.

The mediator asked about their blood type to match recipients with donors. He also offered his services for other organs if needed, as there are “fresh goods everyday”.

The reporters then continued to track Syrians who sold their organs to networks of doctors and mediators.

Donors sell their organs voluntarily to raise money to travel to Europe, or forcibly, as in the case of Ahmed Abdul Karim, who was buried in his hometown of Morek, north of Hamah, next to other bodies whose organs were stolen during medical treatment. These thefts started since 2013, according to locals in nearby villages, as well as human rights and media reports that documented this growing phenomenon as the Syrian war grew fiercer.

On July 6, 2015, the head of Syria’s Doctors’ Syndicate Abdul Qader Hassan announced the dismissal and discipline of five doctors who were found involved in organ trafficking.

Our reporters followed up on the case of these doctors and through a senior judicial source, managed to obtain a copy of the syndicate’s decision to dismiss them.

The document, number 4/3/2011, was issued by the central disciplinary council of the Syrian Doctors’ syndicate.

“The Syndicate has banned the doctors from practicing medicine permanently, referring them to the relevant judiciary authorities after investigations revealed their involvement in a transnational network that takes pregnant women to Lebanon to give birth, before selling their babies for large sums of money for organ harvesting,” the statement read.

According to the statement, the sale took place in compliance with a doctor called Samir H., whom the recipient and donor had met at a conference earlier.

The court based its decision on an initial confession by one of the doctors, as well as his secretary and driver, following extensive investigations, which also included a testimony by one of the victims.

Other doctors led a 12-member network, from Damascus to Aleppo. Our reporters managed to obtain a copy of their case after they were arrested by the criminal security unit in the period between 2013 and 2015.

The network was described by a security source as the “most active”. One of its members would pose as a security officer in charge of an armed group. Some of them had been arrested once before while others were arrested three times in less than two years.

Ziad W. and Mohammed Ammar K. are wanted for organ trafficking. The latter is also wanted for attempted kidnapping for the purpose of debauchery and organ trafficking, according to the police report.

Both reporters found that Ziad and Mohammed Ammar were the doctors whose names were included in the e-records announced by the doctors’ Syndicates of Syria and Aleppo.

Abdul Qader Hassan confirmed that in July 2013, they were dismissed and deprived of their syndicate rights, including pensions, health insurance, personal protection, and medical licenses.

However, according to Hassan, the syndicate cannot take other measures against them, as they no longer live in regime-controlled areas in Aleppo.

Ahmed Sh., Naji F., Mohammed Ghazi S., Ahmed H., Nisreen F., Ahmed H. H., Ibrahim H., and Khaled A. are wanted on charges of organ trafficking, while Fadia D. has also been accused of mediation.

Omar H. is wanted for running a prostitution network with the purpose of organ trafficking.

Ahmed al-Sayyed, the attorney general in Damascus, told our reporters that Syrian courts had processed more than 20 cases related to organ trafficking in the past four years, once a rarity.

Sayyed believes the total number of organ trafficking instances had exceeded 20,000.

Dr. Hussain Nofal, head of the recently-founded general authority for forensic medicine, estimates the number of Syrian cases of organ trafficking at over 18,000 in the past four years.

By early 2013, he says, organs from 15,600 people (out of 62,000 wounded who received treatment in neighbouring countries) had been harvested.

Dr. Nofal based his numbers on a comprehensive study conducted on those who were killed in war zones and border areas. The study includes pictures, videos, and other documents that should be released by the courts later.

If you think children are not affected by organ theft, then you have not heard the story of Yasmin Shahada, 9.

The doctors tried to steal her kidney in a hospital that her family cannot locate until now. She was only identified after three bullets were removed from her body following and injury during clashes in Latakia’s northern countryside in 2013.

Our reporters met with the girl and her father in the neighbourhood of al-Daatour, near the city of Latakia.

According to the father, he was informed on August 4, 2013 that his daughter was dead, so he requested an official death certificate (number 1367) from authorities in the nearby town of Salanfa. However, 17 days later, a Turkish doctor called him and said the girl was alive after surviving an attempt to harvest her organs.

The father expressed gratitude and they agreed to meet at the Kassab border crossing. As the doctor delivered the girl, he told her father about the details of how members of the organ trafficking network agreed to sell her kidney through the hospital.

The deal was made in the presence of the girl before the Turkish doctor saved her and smuggled her to Syria.

During six months of extensive investigations, Both reporters documented 12 cases of organ trafficking through direct interviews with victims in Syria, Istanbul, and Beirut, including seven cases of voluntary donation for economic reasons, three cases of forced organ harvesting during medical treatment after war injuries, one case of survival from a harvesting attempt, and one case of fraud based on a medical excuse.

All cases have been documented through audio-visual recordings. They include victims who are still alive, as well as family members in Syria and neighbouring countries. Yet, there are no accurate official statistics, even though all Syrian officials interviewed in this report have admitted the presence of organised networks that exploit the Syrians’ poor conditions to sell their organs.

Our reporters, using hidden cameras, posed as escorts of patient in Damascus to document the doctors’ involvement.

At 11 am on July, 7, 2015, Thura Ahmed, 16, is accompanied by her parents to undergo a corneal transplant surgery (Keratoplasty) in her left eye at a Damascus hospital.

The girl and her family seemed at ease with the surgery, as the doctor had reassured them about its success rate, how it will be transplanted and the healing period. He said the new cornea would be officially imported from the US for $1,500.

According to the doctor, the surgery has a 95 percent success rate. He said the cornea will arrive with a certificate detailing the donor’s medical information, including the harvest date and the donor being free of any genetic or microbial diseases.

In addition, the doctor said the entire transplant surgery would be recorded on camera as a legal procedure that takes place in all transplant operations.

Two days later, the cornea arrived from the US. “How could it arrive here so quickly?”

The doctor called and said the cornea had arrived, according to the girl’s father. Within 20 minutes, the surgery took place in a hospital near the clinic, but the girl’s condition kept deteriorating.

We showed Thura’s case file to Dr. Mohamed Raslan, head of the state-owned eye bank, which includes the official records of all doctors who import corneas.

According to Article One/B of the legislative decree number 61/2010, the health minister can allow ophthalmologists to import corneas in exceptional cases for limited periods of time and for the public interest.

We compared Thura’s information with official requests made by doctors to import corneas, but we could not find the name of the doctor who performed Thura’s surgery.

We tried to search for Thura’s name in the patients’ database, but we still could not find any record of her.

This means that the cornea was either smuggled into Syria or came from local sources.

While the report was being published, Thura’s family was in the process of submitting a complaint to the doctors’ Syndicate.

In Egypt, home to nearly 132,000 Syrian refugees, 29-year-old Mohamed Zaher (alias) was subjected to a new kind of experience.

An organised group managed to set him up and buy his kidney for a certain amount of money, exploiting his need and ignorance of the country and its laws.

Originally from Homs, Zaher works in auto-repairs. He currently lives in Istanbul, where he moved recently.

Zaher left Cairo after he sold his kidney for $3,000 to someone whose real name he did not even know. All they had was a 15-minute face-to-face conversation to agree on the terms of the deal, including price, time, and place.

We met with him in a house he shares with other Syrians in Istanbul.

Zaher is consumed by regret. Every time he is reminded of the deal, he remembers the tragedy that is yet to end. He does not wish a similar fate upon anyone.

The young man hesitated before he agreed to speak out. No one knows about it, not even his wife, whom he married using the money he made from selling his kidney.

“This is the biggest crime I have ever committed in my life,” he said, “and I will never forgive myself.”

Zaher had just returned from a medical examination, as he went to see a doctor after feeling pain in his remaining kidney.

When the doctor found out he had sold his kidney, he told him: “You will inevitably die if your remaining kidney fails.”

How did Zaher come to decide to sell his kidney? And why? What are the details of the procedure that took place at a Cairo hospital at midnight?

We discussed the case with the Egyptian health ministry. Assistant health minister Saber Ghonaim said that if the hospital was proven to have allowed the Syrian young man’s surgery, the doctor and medical team who performed the surgery would be prosecuted, and possibly suspended.

Ghonaim also said the young man should file an official complaint. However, this is not possible as he is currently not in Egypt.

In addition, the Syrian donor has refrained from any official measures to avoid unnecessary legal consequences.

Zaher’s story in Egypt is not one of its kind. Dozens of other Syrians abroad resorted to social media to sell their organs in order to make ends meet or fund a journey to Europe.

Adverts found on online markets reflect the size of the tragedy, with some people advertising their organs online to flee the tragic situation in Lebanon.

The idea began on social media pages related to migration and Syrians abroad. It has now become the norm. At least one or two new adverts are posted everyday by Syrians who want to sell their organs. There is even a Facebook page called “kidneys for sale”, where donors and brokers discuss their deals.

We tried contacting Facebook to discuss the legality of these pages, as well as the social network’s policy to report them. They replied saying that the pages did not violate Facebook’s standards, as they do not incite violence or post inappropriate pictures.

Organ sale online has even extended beyond kidneys, to liver, lung lobes and anything that could save the donors from their misery.

In March 2015, an UNRWA report revealed that poverty and destitution amongst Syrians had reached 82.5 percent in 2014, compared to 64.8 percent in 2013.

As a result, according to the report, “conflict-related transnational networks and criminal gangs emerged to engage in human trafficking.”

Online investigation

Our reporters infiltrated these networks, posing as brokers searching for organs. They posted an advert on a closed Facebook group for Syrians in Lebanon, asking for kidneys, without specifying a blood type.

Syrian citizen Ali A. offered his kidney for sale, and asked about the price we were willing to pay.

Reporters: $2,000 for one kidney.

Ali: For a poor person, this is a fortune. All I want is to cover my children’s expenses, at least for a couple of months.

The second offer came from Mohamed (alias), a 29 year-old Syrian living in a refugee camp in Rashaya, Lebanon. He is a father of three, including two disabled children who need medical care.

Reporters: How much would you sell one of your kidneys for?

Moahmed: I do not know much about this. If the price is good, I will go ahead with it. I need to go to Europe to treat my kids.

Reporters: How about $4,000?

Mohamed: Yes, I would leave Lebanon and travel immediately to Europe.

On the other hand, we contacted a Syrian refugee who advertised his kidney for sale. He seemed professional, as he mentioned the blood type (B+) in the advert. However, he asked the reporters about the blood type they were looking for, which meant he had access to several kidneys with various blood types.

Reporters: Do you still want to sell the kidney?

Seller: What blood type are you looking for?

Reporters: You said B+ in the advert.

Seller: How much?

Reporters: I do not know. How about $2,000?

Seller: *laughs* I want $10,000.

While markets for selling Syrians as spare parts host deals that occur both behind the scenes and in public, international organizations remain oblivious. Our reporters contacted more than four international organizations concerned with documenting these breaches to enquire about the phenomenon. The responses were either “we do not have any information on the phenomenon” or a complete refusal to respond to the enquiries.

For example, Human Rights Watch wrote back on Sept. 7, 2015 saying: “Unfortunately we have not looked into this matter. You can write to Amnesty international or look into the following journalistic material”. They were referring to a report published in the Oct. 12, 2013 edition of Der Spiegel highlighting the story of Raed, 19, who fled from battles in Aleppo to Lebanon, where he sold his left kidney for $7000. The surgery took place in a secret clinic in a residential complex through a Lebanon-based active network that acquires the organs through a middle man called Abu Hussein. The latter receives a commission of $700. The organs are later sent to GCC countries.

Afterwards, we wrote to Amnesty International, twice. The first time on Sept. 3, 2015 and again on Sept. 8, 2015 but we never received a response. As for the World Health Organization, the reporters received a response after enquiring about its role in monitoring the trafficking of Syrian people’s organs and ways to limit the activity across borders. The WHO response, received on Oct. 29, 2015, stated: “We do not look into the issue of organ trafficking. It is the responsibility of the Interpol. We only examine how countries can prepare organ donation programs and the systems, which may discourage or eradicate the illegal trafficking of organs”.

Doctors without Borders (MSF) did not respond to the reporters’ correspondence sent on Sept. 6, 2015. Their letter was not the only one MSF or other international humanitarian institutions did not reply to.

Dr. Morhaf al-Mialim, in charge of the Syrian Centre for Political and Strategic Studies, claimed that he had written to numerous international organizations since early 2012. Nonetheless, they did not write back. Mr. Nizar Skief, the head of the Syrian Lawyers Union supported this discourse. He said he wrote to the Arab Lawyers Union twice. In the first time he wanted to alert them to crimes committed by Arabs in Syria and in the second time he wanted to shed light on the implication of Arab smugglers in arranging illegal migrations to Europe. Both correspondences were part of his personal effort to look into the matter of trading in Syrians abroad. Nonetheless, his correspondences received no response for the Arab Lawyers Union, which was established in Cairo in 1944.

| Transport method | Transport mechanism | Consequences |

| 1-Sale camouflaged as organ donation within the national borders. | Organ donation is used as a legal loophole, but the transaction comprises a sale agreement between the two parties | The symptoms of having one kidney manifest after an undetermined period of time. |

| 2-Sale abroad in exchange for material gain. | Most refugees suffer terrible economic conditions. As such, they sell their organs either to better their conditions or to flee to Europe. | The symptoms of having one kidney manifest after an undetermined period of time. |

| 3-Secretly stealing non-vital organs | The refugee is persuaded that he/she needs an operation. His/her kidney is removed without him/her knowing. However, he/she soon finds out once the symptoms of the organ removal are experienced | The symptoms of having one kidney manifest after an undetermined period of time. |

| 4-Intentionally stealing vital organs | Occurs in Syria’s neighbouring countries, over borders, or in regions experiencing chaos. | Death |

| 5-Stealing stem cells from corpses or cloning | ||

| 6-Selling sperms or fertilized eggs | A very serious issue, which is rarely looked into. While it is not physically harmful, but the sperms can be used to fertilize an egg and breed embryos. The practice is internationally criminalized. Moreover, whoever purchases sperms uses them to breed illegal children. | Stolen from amongst the deceased’s organs |

| 7-Stealing Placentas and umbilical chords | The placenta and umbilical chord comprise some of the most important stem cells for cloning embryos as they are rich for blood cell. Moreover, people neglect burying them after birth | The placenta is rich in blood cells and can be used to clone embryos. |

Non-Deterrent Punishments

While the Syrian law goes in line with UN conventions on toughening the punishment against human trafficking, the phenomenon has spread during the war. Among the most important agreements signed by Syria is the “United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols”.

Signed by Syria in 2009, the Convention seeks the manner with which to pursue the perpetrators of transnational crimes regardless of the political circumstances. The convention also stipulates the responsibility of the state in combating these crimes. However, Syria has reservations concerning paragraph 2, of article 35 of the convention pertaining to transferring these case to the International Court of Justice

Moreover, the Syrian laws were developed along similar lines. Legislative decree no 3 issued in 2010 deals with human trafficking. It increased the punishment in cases of international crimes or if they are committed against women or children. In the aforementioned cases, article 8 of civic degradation is applied. The later stipulates “whenever there is a reason to increase the punishment, it is increased from the third to the half”. As such, a sentence of 15 years would become 20-22 years and a half, and so on.

The head of the Syrian Lawyers’ Union said: “It is true that the law is a deterrent yet the crime continues”. He added that the “chaos ensuing from the Syrian crisis strengthened organized crime gangs at the expense of parties, who are responsible for pursuing them. Consequently, the phenomenon is likely to expand even further and affect neighbouring countries unless there is an international effort to monitor these crimes and combat them”. The head of the Doctors’ Union agreed with that view. He emphasized that the only way out is through international cooperation to monitor the phenomenon to pursue and capture these networks through international police.

In one of its latest reports on Syria by the United Nations entitled “Squandering Humanity” the issue of trafficking Syrians was highlighted. It spoke about people who are murdered in their country, drown in the sea as they attempt to run for their lives, or who die in hospitals in the pursuit of healing. Those who manage to survive all of that offer themselves and their organs for sale perchance their children can survive.

Editor’s Notes:

The following researchers contributed to this investigation: Hussam al-Agha, Qassem Mohamed, and Mohamed al-Qazzaz.

• This investigation was completed with support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism(ARIJ) www.arij.net and coached by Hammoud al-Mahmoud