EBAS MOUSA – Qamishli

Barely three days after admission to Al-Hikma hospital in the north-eastern Syrian city of Hasakah, Jihan took her last breath to the great astonishment of her family members.

Jihan’s husband, Yasser Mustafa, a man in his forties, could not believe the rapid deterioration in his wife’s condition: “She became sick so I took her to hospital, and on the next day doctors amputated her right foot after a gangrene infection, and then she died” he said in disbelief.

Mustafa tried to save her life by transferring her to the capital Damascus, only to find the doctors telling him “It is too late… there is no hope in saving her life.”

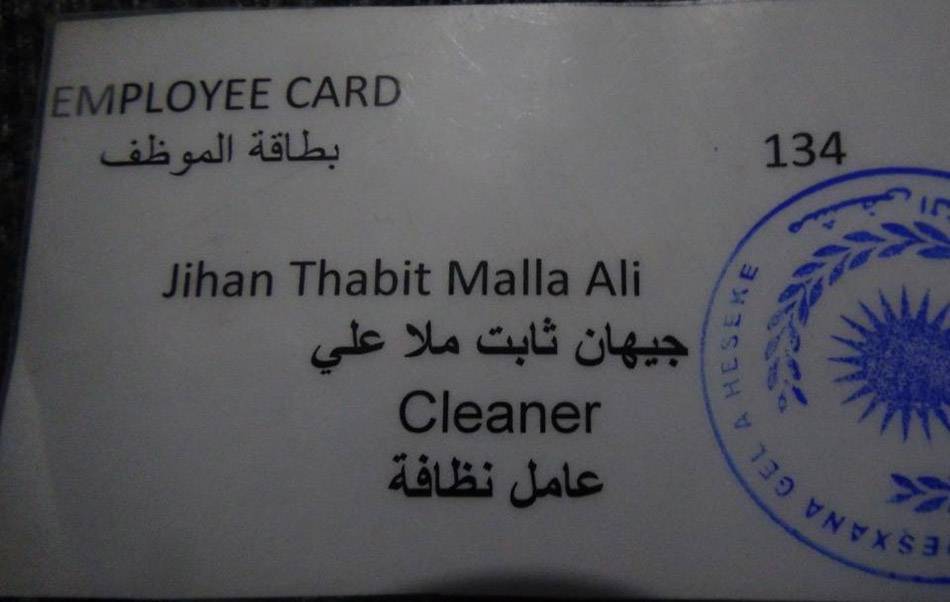

Jihan Mullah Ali was 33 years of age, and had previously taken up a job as a cleaner of operating rooms in the governmental National Hospital in Hasakah, in order to help her husband support their six children. For the next two years she would sterilise and clean operating rooms and doctors’ scalpels while collecting the remains (waste) of surgical operations in bags, according to her husband.

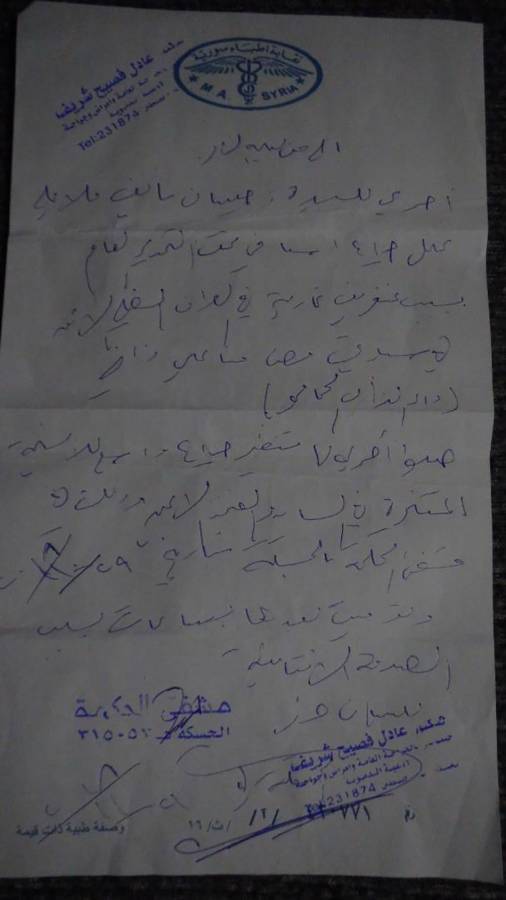

According to doctor Adel Sharif, “Jihan had Lupus, an auto-immune inflammatory disease that attacks the immune system of the body, and this was the reason for her gangrene.” Gangrene is a type of tissue death resultant from a shortage of blood supply or a serious bacterial infection. Sharif proceeds to explain that the nature of Jihan’s work and her exposure to medical waste and remains from operating rooms played a role in her infection.

The medical report on Jihan’s case reveals some further details of her condition: “Ms Jihan Mullah Ali undertook emergency surgery under general anesthesia because of gangrene in the lower-right part of her body as a result of an auto-immune condition (Lupus); she was subject to an endoscopy of her coagulated tissue in her leg and right thigh in the Al-Hikma hospital on the 29th of October 2018, after which she died a from septic shock.”

Mohammad al-Darwish, a doctor specialising in internal disease, explains there are two main causes of Lupus: the first is genetic, the second environmental – the latter which can be spurred on by certain viruses and medications, which raises the likelihood that Jihan’s exposure to medical waste played a key role in her Lupus infection and subsequent death.

In addition to Jihan’s case, this investigation also documents the stories of five other men and women who work in hospitals and medical centres in north-east Syria, and who were infected with chronic and fatal diseases because of their unsafe exposure to medical waste.

This pattern has taken place amidst a failure by hospital cleaners to follow the preventative and safety procedures for dealing with medical waste, and in the absence of oversight and regulation from above.

Accordingly, the problem has been exacerbated by the failure of the hospitals examined in the investigation in the province of Hasakah to apply the safety procedures stipulated in the “national guide for the safe management of healthcare waste in Syria” relating to the collection, transport, storage and discharge of medical waste, which causes nurses and cleaners to handle the medical waste in the same way that they would ordinary rubbish (litter).

The investigation followed and documented the entire journey which medical waste undergoes, starting from its discharge from operating rooms to its placement in normal plastic bags, disposal in municipality garbage trucks and finally its transport to city outskirts where they are burned in a primitive fashion in random pits.

Furthermore, the detailed standards and criteria stipulated in the Syrian Health Ministry’s hospital guides (which stipulates the conditions for the establishment of hospitals before they are built) lack any mention of the need for a medical waste incinerator at the hospital.

According to Yunis Abu Zaid, who works in a medical laboratory in the city of Qamishli: “There are no warnings in public and private hospitals against the spread of certain diseases,” adding that “hospital cleaners are the most exposed to infection because they are less aware of preventative measures than doctors.”

For his part, Shirzad Yusuf, a specialist in general surgery in Qamishli, explains that infection is transmitted after a wound is contaminated by the substance present amongst the patient’s medical waste which carries the virus, adding that the infection rate in the city is high.

Unsafe exposure to medical waste

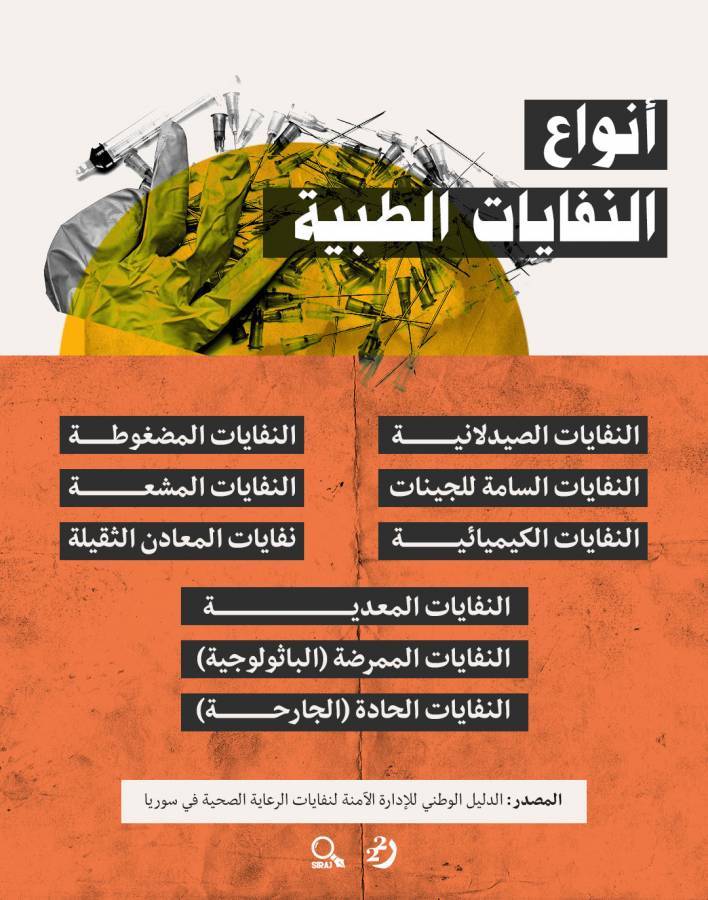

The World Health Organisation defines medical waste as “secondary products of healthcare that encompass sharp and non-sharp objects contaminated with blood, body parts, bodily tissue, chemical substances, pharmaceuticals and radioactive materials.”

WHO affirms that the poor management of health-care waste exposes healthcare workers, waste-handlers, patients and the general community to cases of infection and avoidable toxic effects and injuries.

During a few field visits to public and private hospitals especially in the province of Hasakah, researchers met with workers and doctors, all of whom affirmed the absence of medical incinerators either inside or outside these hospitals; the investigator also inspected and observed the mixing of different types of waste with each other, including sharp medical waste that causes injuries and transmits viruses.

According to Abu Zaid, “the disposal of medical equipment such as needles, scalpels, arterial catheters and laboratory glassware in a rubbish bin without abiding by the safety precautions can lead to injuries and infections being transmitted to patients,” while adding that it is necessary for every hospital to have an incinerator.

It should be noted that healthcare management in the north-eastern region of Jazira (encompassing the provinces of Raqqa, Hasakah, and Deir al-Zor east of the Euphrates) is split between the Syrian government – comprised in the Health Ministry – and the Kurdish-led ‘Autonomous Administration’, with both parties sharing authority in the aforementioned geographical expanse.

The co-president of the “Health Authority” of the Autonomous Administration in the city of Qamishli, Dr Abir Hassaf, admits the existence of a major problem because of the absence of medical waste incinerators, declaring: “The only incinerator is in the city of Derika (Al-Malikiyah), which was installed in 2018 with the aid of an international organization, and is only sufficient for the hospital in that area and the medical centres in its environment.” Hassaf adds that the price of an incinerator is $23,000 US Dollars – or more than 14 million Syrian Liras.

Hassaf justifies the absence of an incinerator by stating that the hospitals in question were built before the establishment of the Autonomous Administration, and therefore the Health Authority is not at fault for the absence of medical waste incinerators. Yet a field visit by the head of the investigation revealed that the eye and heart hospital in the city of Qamishli, managed by the Autonomous Administration’s Health Authority and which opened early on this year, also lacked a medical waste incinerator.

In February 2019, the investigation followed a municipality car collecting and transporting waste starting at Qamishli – after he received a tip that medical waste was disposed of alongside the ordinary rubbish which the car transported.

A cleaner in the ‘National Hospital’ in Hasakah told Raseef22 that medical waste, including bags of blood, empty and used syringes, body parts, soiled dressings and scalpels used in surgery were collected in specific bins placed in the hospital’s corridors, before the bins are emptied in a dumpster whose contents are then thrown in the back of municipality garbage trucks without wearing any gloves; the municipality’s cleaners than mix the medical waste with general waste inside the garbage truck. Finally, the waste is transported and incinerated.

The garbage truck’s journey ended in the ‘Nafkari’ landfill near the city of Qamishli, after having passed through several hospitals and medical centers to collect their medical waste, which is then piled up, accumulated and intermittently set on fire, so that the fire is not extinguished. Even after the combustion process was over, the investigator found the remnants of medical waste in the landfill, including catheters, vaccines and bottles of medication, amongst others.

From Cleaning the Nephrology Units to Kidney Failure

42-year old Wa’il al-Salem cleaned units at the nephrology department in al-Hasakah’s National Hospital between the years 2015-2017. He would receive 70,000 Syrian Liras ($120 US Dollars) every month for his work in order to support his family of eight only to eventually succumb himself to kidney failure and lose his job.

“I used to clean the floors of the nephrology department in the hospital, and often collected waste without wearing medical gloves, while I sometimes wore [medical] face masks” al-Salem says.

After a period of time, Wa’il started to feel exhausted and was unable to go to work; he returned to the same hospital he worked in to undergo a medical examination, only to discover that his kidneys were failing and he additionally had high blood pressure and a calcium deficiency, according to the medical report examined by the investigator.

During the investigator’s meeting with Wa’il, he noticed that he appeared very weak and also had rashes on his skin, which meant that he had to undertake repeated dialysis sessions.

Wa’il explained that most of the rubbish which he collected as a cleaner in the nephrology department contained bags of serum, needles, soiled dressings and blood-soaked cotton.

Faisal Askar is a specialist in internal medicine; he believes that the country’s conditions following the outbreak of the Syrian war in 2011 led to a decline in health and cultural standards, and consequently to the appearance of certain septic diseases such as brucellosis, typhoid and hepatitis A, B and C – which often in turn led to patient dehydration and acute kidney failure, both in the general public and to those working in the medical field.

Askar called for the “necessity of reviewing the training of medical cadres to avoid any medical defects.

Lack of Prevention

Aisha Helal – 39 years-old – has worked as a cleaner in the emergency department in the National Hospital in Hasakah for the past three years. She earns a salary of 80,000 Liras ($150 US Dollars) monthly to support her special-needs husband and four children. However, as with others she began to suffer a severe difficulty in her breathing and a fast heart-beat during her work. She says that she has since spent 200,000 Liras on treatment.

Explaining how she contracted her illness, Helal said: “Every day I carry the bins that are filled with medical waste from the emergency department to the main rubbish containers in the hospital, and I clean the floors from medical waste and blood, needles and other things.” Helal goes on to confirm that she did not wear gloves or medical masks during her work, stating that she did not feel comfortable when doing so and never even tried it, despite their availability in the hospital.

According to Abdul Rahman Amin – Aisha’s doctor – the patient had a chronic allergy that was exacerbated when exposed to dust, cleaning substances and waste from surgical operations.”

As with the case of Aisha, most cleaners inside hospitals and medical centres do not wear precautionary gloves or masks, a reality also extending to the approximately 2,000 municipality cleaners who handle the waste outside of hospitals, according to Tariq Mohammad, who works in the Environmental Office in the Municipalities’ Committee in the Municipality of Qamishli.

These workers are often exposed to medical waste without taking any preventive or precautionary measures. The compiler of the investigation similarly found that municipality workers did not wear medical gloves designed to prevent the spread of viruses despite their availability in hospitals, and in the absence of any oversight or regulation that compels them to wear it.

We put these findings to the head of the Autonomous Administration’s Health Authority Hassaf, who responded: “Gloves are available in hospitals, and if they are not worn by cleaners then they are not following hygiene standards.” As regarding the municipality’s cleaners, Hassaf blamed the health department in the municipalities for not enforcing regulations on their workers.

No Vaccines, No Tests

Sulaiman Ahmed, a doctor in the province of Hasakah, stresses the need for workers to undergo medical tests before being accepted for work, in order to make sure that they were not infected by certain diseases, such as tuberculosis and hepatitis, noting that these are necessary tests because of their contagious nature which can be transmitted through blood or breathing.

As for the post-recruitment stage and how to deal with medical waste once inside work, Ahmad states that the workers are obligated to undertake a periodic test to check for communicable diseases, not least because of the fact that medical waste is contaminated with diseases – with various diseases being transmittable through needles, syringes and scalpels, and through piercings and wounds.

Ahmed stresses that hepatitis vaccines have to be taken over several intervals, in the event that a person did not have Hepatitis B. The first vaccine dose is followed by a second after a month, a third after six months and a fourth after four years – after which it is possible to take a supplementary supportive dose.

Through its co-president Abir Hassaf, the Autonomous Administration’s Health Authority admits that it has not conducted hepatitis tests for hospital workers, attributing the reason to the absence of vaccines – with the World Health Organization only providing the Syrian government, and not the Autonomous Administration, with vaccines as the only ‘recognised’ authority in Syria.

Hassaf clarified however that an understanding has since been reached with the World Health Organization by which vaccines would be provided; however, medical tests for workers have to be conducted before the immunisation can take place, a process which Hassaf says has so far not happened, alluding to the fault of local municipalities.

The head of the investigation attempted to reach the World Health Organisation on the 16th and 28thof March 2019 by email, in order to further examine the case and its findings, but did not receive a response up to the publication of the investigation.

Unenforced Laws

Amongst the most prominent reasons for the establishment of hospitals without medical waste incinerators is the failure to enforce the Syrian hygiene law which obligates the acquisition of these incinerators – the absence of which have led to most hospitals in the al-Jazira region dispose of medical waste in an unsafe manner.

Accordingly, the fifth chapter of the Syrian Hygiene Law (no. 49 for the year 2004) set out the mechanism for dealing with medical waste – however, this mechanism remains unenforced in the country’s north-east.

Article 23 of the law stipulates that owners of medical facilities have to segregate the different types of medical waste (non-hazardous from hazardous), with each labelled accordingly and placed in specific rubbish containers.

Article 24 of the law meanwhile obligated those transporting medical waste to not mix it with any other rubbish, and to subject it to hygienic and safe treatment; Article 25 delineates the need to provide cooling (refrigeration) units for the medical waste in the event that they are stored for 48 hours – a requirement which the investigation showed has not been followed.

As for the means of disposal, the Syrian Health Ministry stipulated six methods, the most important of which was to burn them at high temperatures in specific medical ovens.

It should be noted that the city of Qamishli contains 10 private hospitals and one public (governmental) hospital, as well as tens of medical centres, according to a chart published by the Syrian Health Ministry.

According to a 2015 report by the Roj Centre for the Protection of the Environment, hospitals leave behind almost two tons of medical waste every week, with a small hospital of 25 beds producing approximately 10 kilograms of waste.

Environmental Damage

The negative impacts of incinerating medical waste in landfills do not only encompass workers being infected with disease, but also includes the environment through the emissions produced by the unsafe incineration of medical waste.

According to Dilibirine Mohammad, a member of the board of trustees of the local Keskayi Organisation for the Protection of the Environment: “Dumping medical waste with general rubbish leads to the altering of the composition of the waste by changing its contents – thus transforming it from normal substances to toxic substances which are hazardous to both humans and the environment.”

Mohammad explains that the primitive incineration of medical waste releases a huge quantity of pollutants, including heavy metals such as arsenic, chromium, brass, mercury and lead which accumulate in drinking water, soil, plants and animal bodies – adding that the imbibing of high concentrations of these minerals by humans has toxic effects, especially lead and arsenic.

According to a 2018 study by the World Health Organisation titled “Healthcare waste”, the unsafe burning of medical waste and inappropriate substances leads to the release of pollutants into the atmosphere and the release of ash residue, explaining that the burnt substances that include PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), dioxins and furans are cancerous substances which have been linked to an assortment of damaging effects to human health.

The study further illustrated that medical waste landfills can poison drinking water if they are not safely constructed, stressing the need to use modern incinerators that operate at a high temperature ranging between 850°-1100°C, and equipped with special equipment to discharge gases safely; these alone fulfill international standards on dioxin and furan emissions, with the burning of medical waste constituting one of the main sources of dioxins, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Dioxin is the common name given to a group of 75 purely toxic chemicals which form from the combustion of waste that contains chlorine or through the production of products that contain chlorine.

Ultimately, despite it being more than a year since Jihan Mullah Ali’s passing, her husband still digs up her old pictures, reminiscing on their nine-month long engagement and the beautiful days they spent together. Today, Jihan’s husband worries about the future of his x children who were deprived early on in their lives from their mother’s care, who went from being a worker who helped people to survive with their lives to a victim that lost her life as a result of their medical waste.

*This investigation was accomplished with support from (SIRAJ), and under the supervision of Ahmed Haj Hamdo. Published on Raseef22