On June 23, 2024, it was an ordinary day for journalist Haneen Imran, 26, as she moved around the Syrian capital, Damascus, running her daily errands. What she did not know was that Syrian security services were tracking her movements and would arrest her later that day, just minutes after she settled in a specific location.

That day, Haneen, who was working from Damascus with media outlets opposed to the Assad regime under pseudonyms, moved through several neighborhoods in the city. Around midday, she entered an educational center to use its internet connection and electricity. Suddenly, an unfamiliar man entered one of the halls, quickly scanned those present, and left. Minutes later, he returned and asked everyone to present their personal identification.

He began with journalist Haneen, who was sitting near the entrance. After identifying himself as an officer from the Political Security Directorate, he took her ID card. He did not check the documents of anyone else in the room because Haneen was the target.

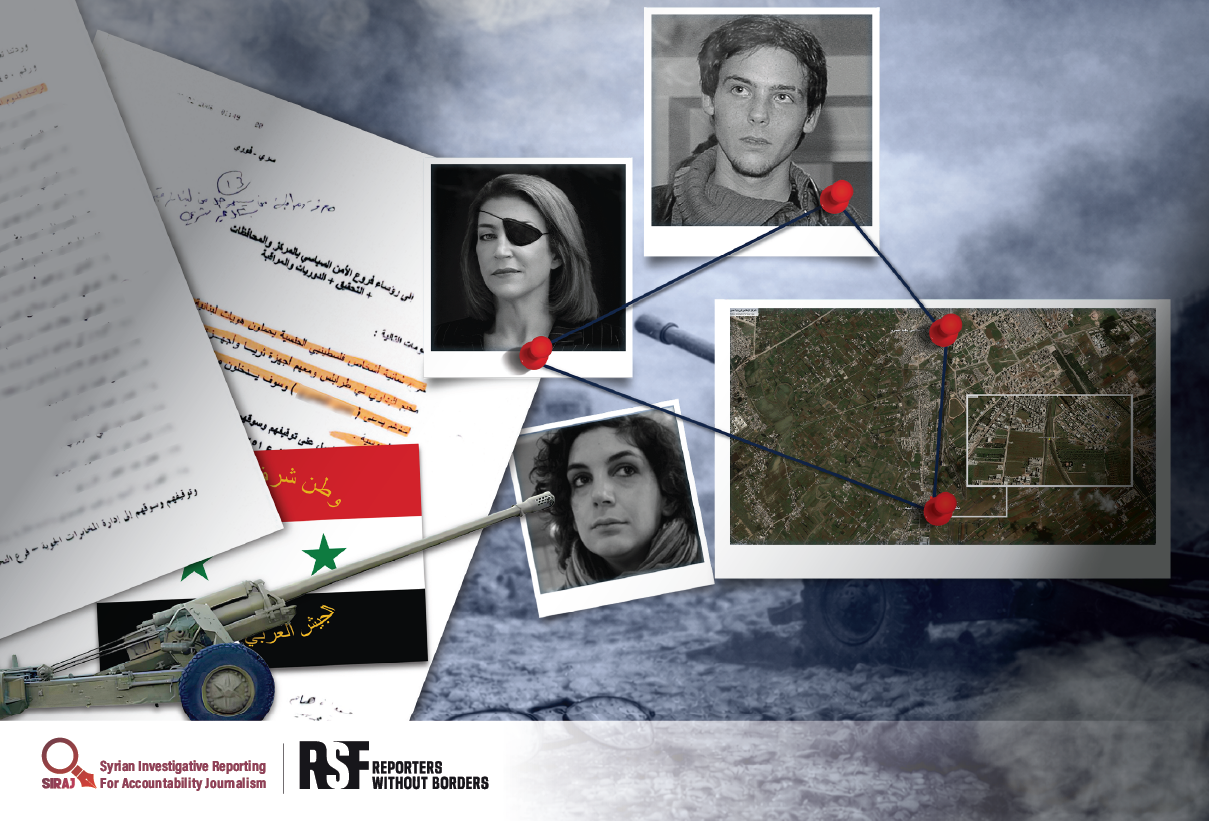

Haneen was arrested and transferred to the Air Force Intelligence branch at Mezzeh Military Airport. During her detention, she was subjected to various forms of torture, both during interrogation and outside it, after investigators retrieved all the data from her communication devices. “I ended up in the hospital,” she told the investigation team, explaining that she was arrested through surveillance of her communications. She believes she was tracked by a device known locally as al-Rashida, technically referred to as an IMSI catcher.

“Shortly before my arrest, I started receiving SMS messages to reset passwords on my phone,” Haneen said. “When I was arrested, I saw three cars parked outside. The arrest happened just minutes after I arrived at the center and sat down.”

Haneen was not the only person arrested after being tracked through surveillance technologies under the former Assad regime. Arrest records show dozens of “targets” detained after being digitally monitored by security forces during Bashar al-Assad’s rule.

The technologies used by the Assad regime to spy on Syrians and arrest them are typically employed by states to protect national security and combat organized crime. Assad, however, repurposed these capabilities to pursue political opponents—and later, individuals involved in business activities.

This occurred at a time when the Syrian regime and its allies on Syrian territory (Hezbollah and Iran) were themselves subject to Israeli intelligence penetration.

Digital copies of documents shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) as part of the “Damascus Dossier” project with the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism – SIRAJ, reveal that before its fall, the Assad regime received training from technical and intelligence specialists from the People’s Republic of China and Iran on the use of so-called Rashida devices—4G systems designed to “track wanted individuals” and apprehend them.

The Damascus Dossier project is a collaborative investigative initiative led by the ICIJ, in partnership with Germany’s public broadcaster NDR. It brings together journalists from around the world to uncover new and disturbing details about one of the most brutal state-run killing systems of the 21st century: the regime of former Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

ICIJ, NDR, SIRAJ, and 126 journalists from 24 partner media organizations across 20 countries spent more than eight months organizing and analyzing the documents, consulting experts, and interviewing Syrian families still searching for loved ones who disappeared during Assad’s rule.

The Damascus Dossier project exposes the internal structure of Assad’s security apparatus and its connections to foreign governments and international organizations. The leak comprises more than 134,000 files and documents, primarily in Arabic, amounting to approximately 243 gigabytes of data.

The documents span more than three decades, from 1994 to December 2024, and originate from Air Force Intelligence and the General Intelligence Directorate in Syria.

Both agencies have been subjected to extensive U.S. and European sanctions due to their brutal practices, including torture and sexual violence.

The leaked materials include internal memos, reports, and correspondence that reveal the day-to-day operational mechanisms of Assad’s surveillance and detention network, as well as coordination with foreign allies such as Russia and Iran, and communications with UN-affiliated agencies operating inside Syria. The highly sensitive database also contains the names of several former Syrian intelligence officers.

The Assad regime continued training its personnel on the use of Rashida 4G devices until the end of 2024. Digital images of documents reviewed by the investigation team, dated 2023, show that several intelligence officers received advanced training on Rashida 4G systems from what the documents refer to as “Chinese friends.”

In 2024, intelligence services continued—and intensified—this training program.

In addition, Assad adapted all available tracking systems to ensure the survival of his rule, including the pursuit of political opponents and individuals who possess foreign currency.

The Rashida, internationally known as an IMSI catcher (International Mobile Subscriber Identity catcher), is a device that intercepts mobile phone signals and captures the unique international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) associated with them.

Training Under the Supervision of “Chinese Friends”

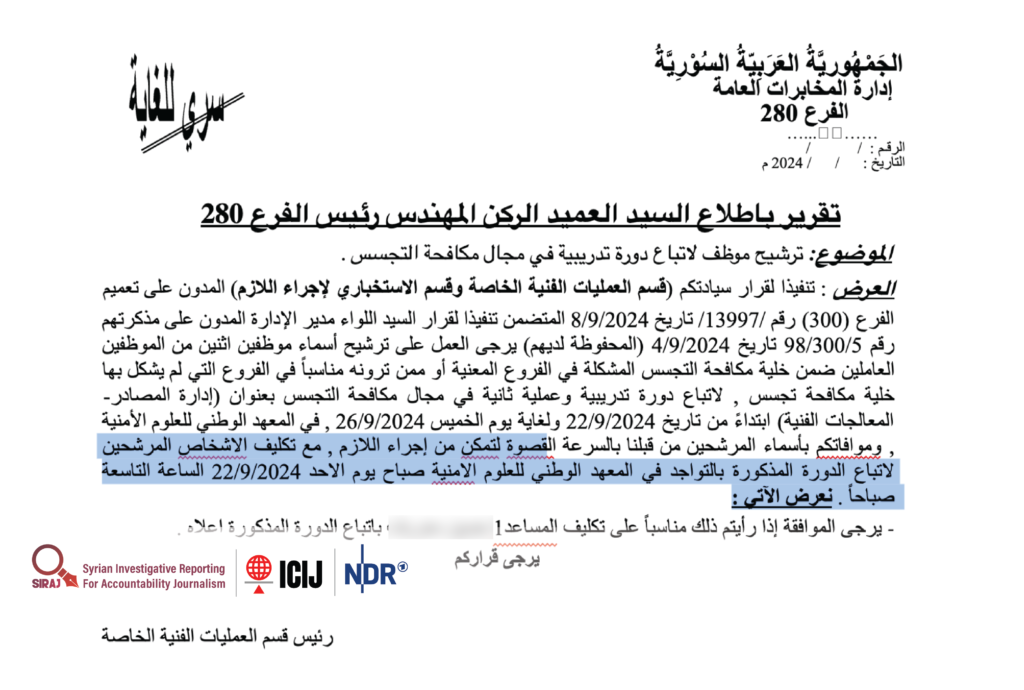

In September 2024, as the Assad regime was struggling to survive amid growing international isolation and the mounting impact of sanctions under the Caesar Act, intelligence agencies were keen to enhance their counter-espionage capabilities. They organized specialized training courses to that end.

A classified cable titled “Report for the Attention of Brigadier Engineer, Head of Branch 280” was issued under a Top Secret designation.

According to the document, a request was made to “nominate an employee to attend a training course in counter-espionage.” The cable asked the brigadier to nominate two employees to attend a second round of practical training on “source management and technical processing.” Shortly thereafter, Warrant Officer First Class Hussein was assigned to attend the course.

In the same context, a covert tracking system was installed, and personnel were trained to operate it and follow protocols for coordinating with the Communications Directorate to meet target-tracking requirements. Ten intelligence officers from the Directorate were trained on operating the Rashida system for covert tracking and on carrying out training missions to increase their operational readiness and tracking capabilities.

These developments formed part of a comprehensive work plan detailed in a document titled “Tasks Accomplished in 2023,” which also records the “implementation of a training course for personnel under the supervision of Chinese friends on the use of the Rashida (4G).”

Tracking operations carried out by Assad’s intelligence services in 2023

Rim Kamal, a legal officer in the Human Rights and Business Unit at the Syrian Legal Development Programme (SLDP), said that surveillance constitutes a violation of privacy, but what follows can amount to crimes against humanity, such as torture and enforced disappearance.

“This means that companies involved may have contributed to international crimes,” she noted, adding that several countries have enacted laws to regulate corporate activities and mitigate risks associated with their operations.

She also pointed to the European Union’s recent adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which imposes a legal obligation on large companies—including certain non-EU companies operating within the European market—to identify, prevent, and address human rights and environmental risks and adverse impacts throughout their supply and value chains.

Targets Under Surveillance

Another exclusive document indicates that a group of targets referred by the Director of the General Intelligence Directorate was processed, detained, and arrested. Additional cases were handled based on information received by the Directorate through officers of Branch 280 and other intelligence sources.

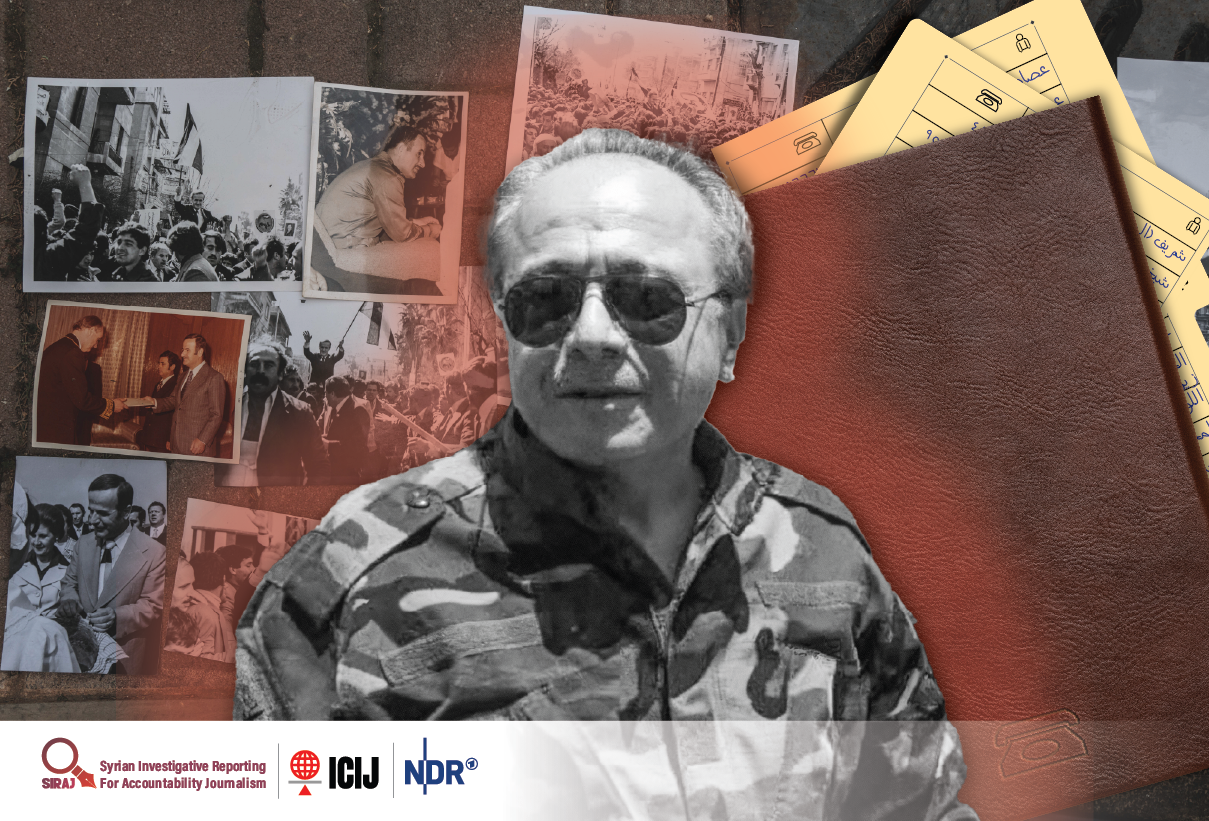

At the time, the Syrian intelligence apparatus was headed by Hossam Louqa (born 1964), a Syrian intelligence officer believed to be currently in Russia. Louqa served as Director of the General Intelligence Directorate from 2019 until the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024.

Drawing on decades of experience within Syria’s security services, Louqa played a central role in strengthening the country’s intelligence community and was known for his involvement in a wide range of security and intelligence operations inside Syria.

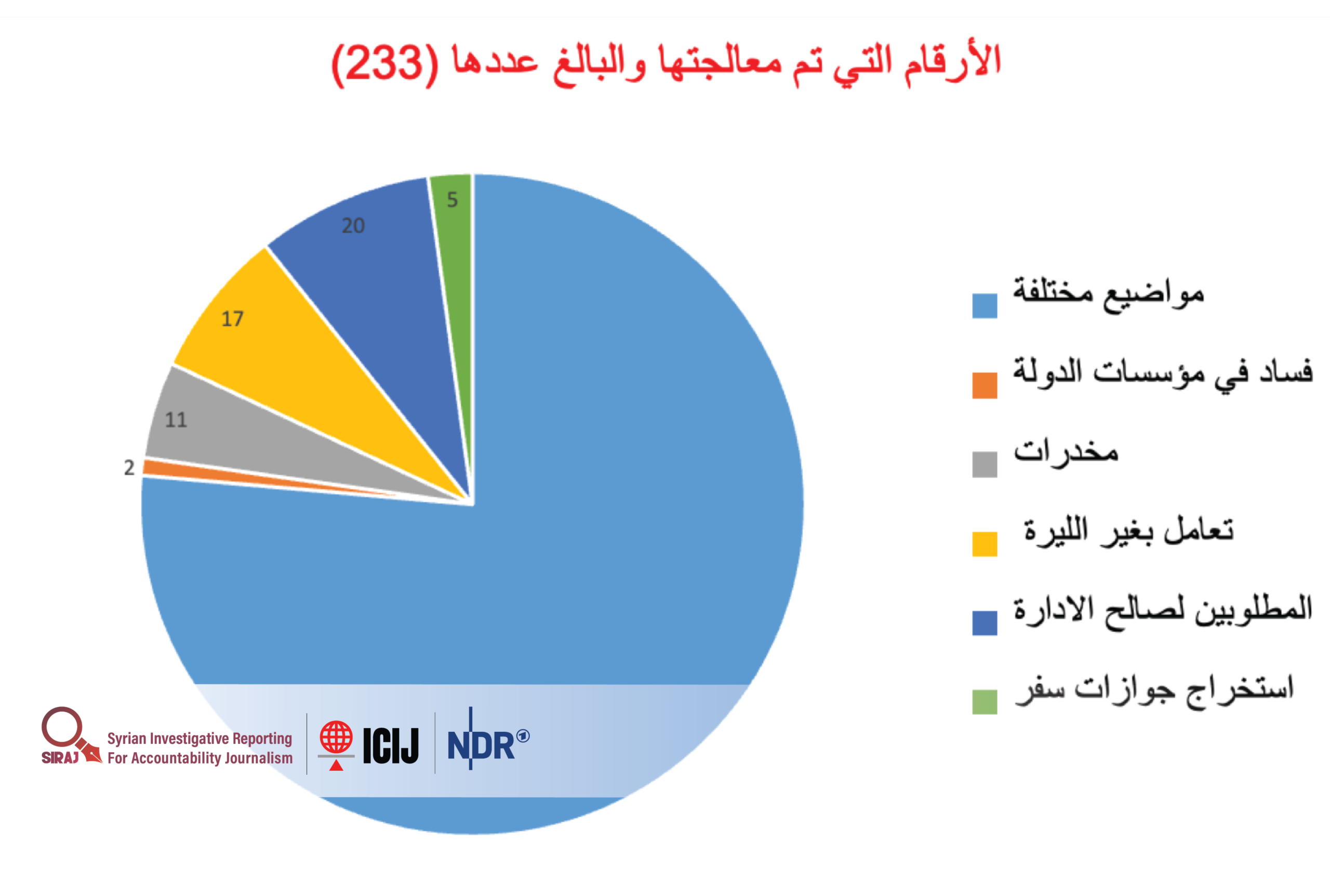

Under Louqa’s supervision, 233 targets (see illustration below)—all civilians—were tracked to arrest them. Among these were:

- 178 cases under unspecified “various topics,”

- two cases involving corruption in state institutions,

- five cases related to passport issuance,

- 11 drug-related cases,

- 17 cases involving transactions conducted in currencies other than the Syrian pound, and

20 individuals wanted by the intelligence services.

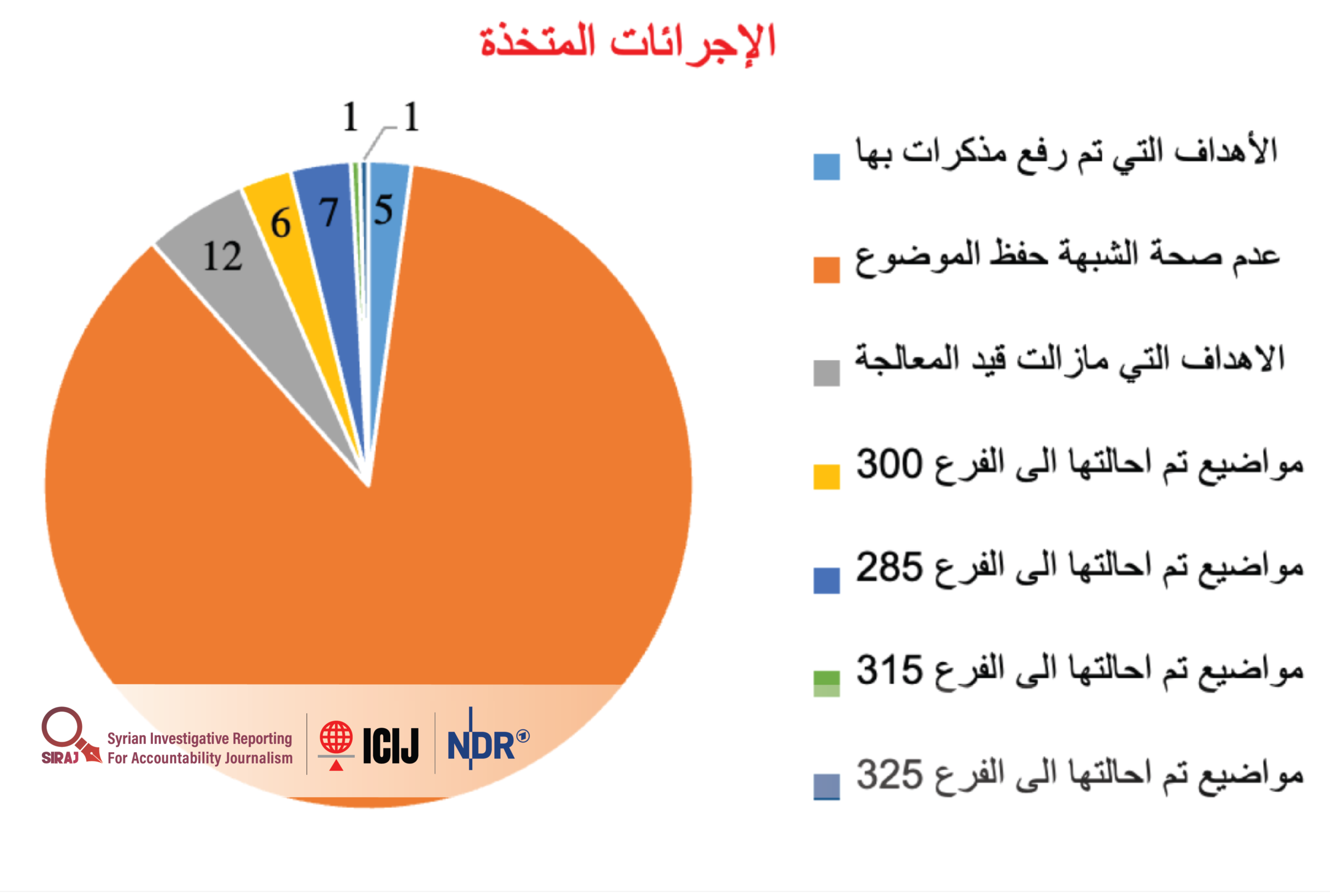

Of the 233 tracked targets, surveillance and follow-up memos were issued for five wanted individuals, while 12 targets remained under processing. Six targets were referred to Branch 300, seven to Branch 285, and the remaining cases to Branches 235 and 315.

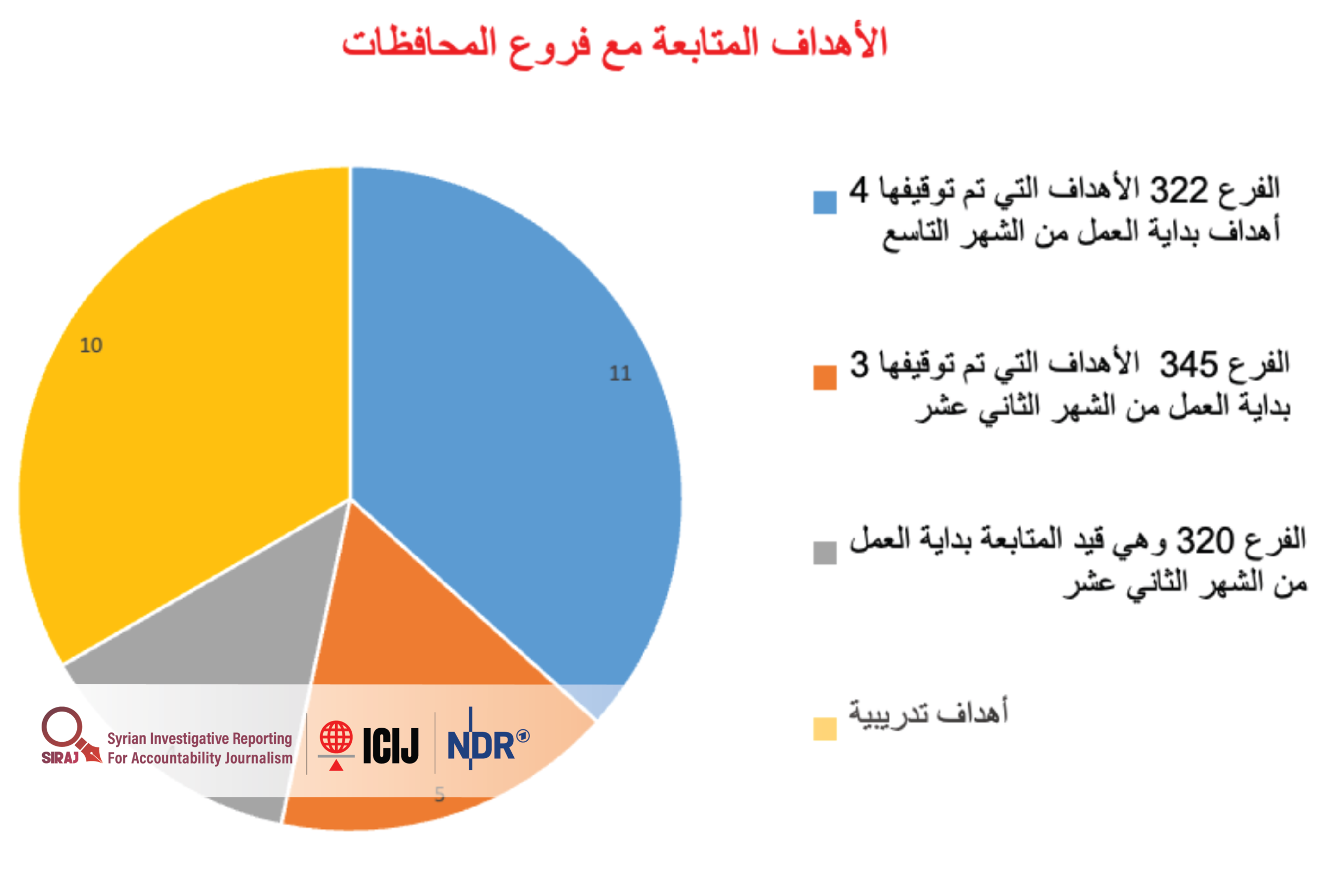

A document summarizing activities completed in 2023 states that intelligence branches cooperated to arrest targets referred to them through the Rashida system. In the final quarter of that year, 30 targets were tracked, and seven arrests were carried out. These included 11 targets linked to Branch 322 (four arrested), five targets linked to Branch 345, four targets linked to Branch 320, and ten training targets.

Each year, intelligence branches compiled summaries of their surveillance activities in a file known as “System Targets.” The investigation team reviewed a document detailing targets tracked by the surveillance system between 2019 and 2024.

For each target, multiple phone numbers were listed, along with the names of subscribers and the alleged charges justifying surveillance. The records show hundreds of mobile numbers linked to their owners, locations, and accusations ranging from political to economic offenses—such as “communicating with a terrorist,” “special target,” “livestock smuggling,” or “discussing weapons.”

In some cases, targets were pursued for contacting a Lebanese number and insulting Hezbollah, while others were accused of conducting transactions in foreign currency. The final outcome for each target was recorded, often indicating arrest and detention, continued pursuit, or failure due to phone line deactivation. In some instances, surveillance led to numbers registered to individuals already detained, with the SIM card later reused by another person. Others were arrested after being tracked through their IMEI.

In an undated document reviewed by the investigation team—believed to date to 2024—Branch 280 of the General Intelligence Directorate offered assistance in tracking 19 individuals in November, shortly before Assad’s fall, using Rashida 4G devices. Four notorious security branches known for repression and torture—Branches 322, 318, 325, and Counter-Espionage Branch 300—jointly requested the arrest of these 19 individuals. Four of them were arrested using the Rashida systems.

Abusive Use of Technology

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, the Assad regime has systematically exploited technology to entrap opponents. Internet services were cut off from entire communities that relied on social media to report violations against civilians during protests against Assad.

Mehran Ayoun, director of the Salamtek team specializing in digital security and digital citizenship, said: “In the early days of the Syrian revolution, communications were completely cut off from the city of Douma and its surroundings. Yet at the same time, phones inside the city were receiving a signal, confirming the presence of Rashida devices impersonating cell towers.”

Ayoun added that in its final phase before collapse, the regime increasingly used Rashida devices to track traders and individuals engaged in financial activities, aiming to extract as much money as possible—not for criminal investigations or the public interest. He noted that in the final period before Assad’s fall, there was no revolutionary or military activity in major cities, particularly Damascus.

He emphasized that while states may possess IMSI catchers, their use normally requires a judicial warrant and must serve the public interest. Unauthorized data interception results in prosecutions and financial penalties—something that never occurred under the fallen regime.

Waseem Hassan, a telecommunications engineer who previously worked on building Damascus’s Al-Nasr Exchange within the central Operations and Maintenance Center (OMC) for landline communications, said that the rear section of the Al-Nasr Exchange building was—and remains—responsible for monitoring and controlling all communications in Syria. The same building housed communications monitoring rooms operated by Branch 225.

Hassan defected and left Syria after Branch 225 tasked him with developing an algorithm to detect relationships among callers. “If a group of people frequently call each other, that indicates they are an organized coordination group,” he said.

“At the time, the head of Branch 225, a brigadier, told me I had full authority to assemble a team of engineers and programmers to develop the algorithm internally, because procuring it from abroad would require a tender process and too much time.”

Before defecting in the early days of the Syrian revolution, Waseem Hassan accompanied one of his colleagues on a multi-day tour with technical equipment. He later discovered that the device was using a Rashida system, without his knowledge at the time of what kind of data was being collected. Prior to the mission, a communications antenna had been installed on the vehicle and connected to the device.

Intelligence Training in China

Possessing IMSI catcher devices is not, in itself, a violation. Most countries around the world own similar equipment, typically using it for strictly security and military purposes, in wartime, or to maintain public order and combat organized crime. However, following the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, the Bashar al-Assad regime expanded its surveillance capabilities by acquiring new 4G Rashida systems and receiving technical training with direct assistance from China, then a key ally of the regime.

Syrian-Chinese relations date back to 1956, following Syria’s independence. During the Cold War and throughout the 1990s, relations remained limited before improving significantly in the early 2000s, driven by increased trade and economic exchanges.

By 2004, economic cooperation had grown substantially, with China becoming one of Syria’s largest suppliers of goods. Documents from Syria’s Air Force Intelligence indicate that between 2012 and 2024, Syrian intelligence officers and military personnel received training in various technical fields from Chinese military and intelligence officials. Syrian delegations traveled repeatedly to China for this purpose.

Documents dating back to 2012 show that the leadership of Air Force Intelligence sent several military personnel to China to attend a three-and-a-half-month workshop on YLG-6M military radar systems.

One document reviewed by the investigation team lists the names of Syrian officers dispatched to China for training in various fields related to communications and defense. These officers were nominated by Air Force Intelligence, which at the time was headed by Jamil Hassan, who is subject to both U.S. and EU sanctions.

China was among the countries that politically supported the Assad regime during the years of the revolution and used its veto power multiple times at the UN Security Council to block resolutions condemning Assad.

Neither the Chinese Embassy in Berlin nor the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded to requests for comment from the investigation team and journalists from Germany’s public broadcaster NDR.

Data Extraction and Lock-Breaking Capabilities

Under Assad, security services also conducted training programs under Iranian supervision, which included equipping a so-called “Lock Unit” within one intelligence branch with specialized devices to open various types of locks. The unit received manual tools for opening vehicles, duplicating keys, detecting lock frequencies, and copying them onto new keys.

According to a document outlining activities completed in 2023, a training course was conducted to “qualify Syrian intelligence personnel in opening residential and office locks.”

In parallel, the Digital Crime Detection Unit was equipped with advanced skills, including specialized training in data recovery from hard drives, USB flash drives, and memory cards, particularly from damaged devices.

Syrian intelligence sought to further enhance its technical capabilities with Iranian support by keeping pace with modern applications, monitoring and tracking social media, and employing social engineering techniques, in addition to training in opening modern mechanical locks and electronic and mechanical safes.

Intelligence officers also received training in opening modern biometric vehicles, cloning frequencies of modern car remote controls, and acquiring the necessary tools and equipment for such operations.

Documents from Syrian intelligence dated 2012–2014 indicate that Iran trained Syrian military personnel, including on how to respond to unguided missile attacks on aircraft. The documents also allege that Iran assisted in maintaining Syrian government aircraft on several occasions and sold aircraft to Syria.

Another document from 2018 refers to a chemical weapons facility in Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus (Haran al-Awamid), reportedly operated primarily by Iranian workers.

Another document dated 2023 indicates that “Iranian colleagues” trained Syrian intelligence officers in opening vehicle, office, and residential locks and duplicating keys—training that appears aimed at improving their ability to pursue intelligence targets.

Neither the Iranian Ministry of Justice nor the Office of the Supreme Leader responded to requests for comment from the investigation team and NDR journalists.

Surveillance Technology Before the Syrian Revolution

The Assad regime had a long-standing history of importing surveillance technologies and electronic equipment to monitor communications and internet traffic.

Open-source research identified several companies worldwide that supplied the Syrian regime with surveillance technologies prior to the uprising, showing how the regime acquired communications equipment that enabled the tracking, arrest, and torture of dissidents based on intercepted calls and communications.

One month before the Syrian uprising began, in February 2011, the regime obtained a U.S.-made Central Monitoring System (CMS), supplied to the Syrian Telecommunications Establishment.

The supplier later paid a USD 100,000 fine to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security.

The system was capable of collecting data on internet browsing, email, online chat, and Voice over IP (VoIP) calls. The U.S. State Department concluded that the system could be used by the Syrian government to intensify repression against the Syrian population.

The regime also acquired Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technologies, enabling intelligence services to monitor internet activity, including browsing and email communications. One company reportedly sold DPI systems that could be used by the Syrian regime for surveillance purposes.

Following the outbreak of the revolution in March 2011 and the imposition of international sanctions, the Assad regime appears to have turned increasingly to China for technological systems. Numerous Chinese companies have faced allegations of selling telecommunications equipment to authoritarian regimes such as Iran and Syria. A Reuters report revealed that Chinese tech giant Huawei used front companies under names such as Skycom and Canicula.

Assad’s Interest in Chinese Technology

Months before the regime’s fall, Branch 280 prepared a detailed study of a Chinese company, which was reviewed by the investigation team. The study included extensive information about the company’s smart solutions, related systems, and technologies involving identity verification, data storage, and transportation systems. However, it remains unverified whether the company supplied any equipment to the Assad regime or established any commercial relationship with it.

Engineer Waseem Hassan said, “During my work, most of the equipment came from Huawei. They provided all the technologies and equipment, to the extent that employees competed to be selected for training missions to China.”

He added that in 2011, following sanctions and the withdrawal of many companies from Syria, Huawei significantly expanded its presence with the Syrian government.

“I personally worked with Chinese technicians who came to install servers and other equipment. Chinese experts were continuously operating at the Syrian Telecommunications Establishment,” he said.

According to a report by SC Media, multiple companies in Hong Kong and China sold Rashida (IMSI catcher) devices on the black market for up to USD 15,000, contingent on “promises of legal use.”

Legal Responsibility of Companies

Rim Kamal, a legal officer at the Human Rights and Business Unit of the Syrian Legal Development Programme (SLDP), said there are legal consequences in such cases.

“Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies can become involved in violations in several ways.”

She added that even if companies do not directly cause harm, they may be complicit through intermediaries.

“It is the responsibility of the selling company to know who will ultimately benefit from this technology before completing the sale,” Kamal said.

Access to Sensitive Data Without Judicial Authorization

Digital copies of documents reviewed by the investigation team show that security agencies had access to sensitive information on all mobile phone users.

Security branches routinely submitted names, phone numbers, or national identification numbers to Branch 300, which coordinated with the Communications Directorate to retrieve data such as incoming and outgoing calls, subscriber identity, last known geographic location, and in some cases, recorded call and message content—confirming expert testimony.

When asked whether security agencies could access subscriber systems without facilitation or consent from telecom companies, Alaa Ghazzal, a digital safety and information security specialist, explained: “Most systems—particularly subscriber identity, coverage, IMEI, and IMSI systems—require telecom companies to grant access in order to retrieve data.”

He added that telecom companies control both subscriber identity systems and coverage systems.

Subscriber identity systems provide phone number data, including subscriber identity, point and date of purchase, and sales outlet information. Coverage systems provide data on cell towers connected to a device or number, enabling location tracking.

Mehran Ayoun, director of the Salamtek digital security and digital citizenship team, said:

“This means that security branches have access to telecom companies’ infrastructure, as evidenced by their ability to know when someone uses a new phone number or to identify all numbers associated with an individual via their national ID.”

Neither Syriatel nor MTN, Syria’s two mobile phone operators, responded to questions from the investigation team regarding intelligence access to sensitive user data or the role of cell towers in facilitating arrests.

Creative coordination and visual solutions: Radwan Awad

Research contribution: Wael Qarsaifi