Ahmad* is 11 and has lost his hacksaw – or rather, it was stolen by a man whom he recognises as a former soldier of the toppled Syrian regime. Only now, the man haunts the ruins of Damascus’s periphery with a pistol, clad in civilian clothes.

Without the hacksaw, the day’s haul is paltry. He and his friend Basel*, two years his senior, used the fine-toothed blades to weaken the steel rods sticking out of building debris, then twisted them until they snapped. They must now resort to picking up scrap off cuts, but after months of scavenging among the same mounds of grey rubble- once opposition suburbs turned battlefield during the 14 years of war – there is only so much left.

To them, steel scrap fetches only 500 Syrian pounds per kilo – the equivalent of four US cents. On a good day, their harvest might come to 25 kilos. On a bad day, a meagre ten. It’s a risky business, and they know it, but it reportedly pays more than picking up plastic.

While Ahmad and Basel’s day is slow, around them, others are swarming across the blasted land. They drift in and out of the scene, swallowed by the open bellies of the buildings, only to resurface in their gouged-out undergrounds, as they pick their way across a pale blanket of shattered masonry, perhaps just inches away from the next sleeping mortar round.

They are covered in multiple layers of clothes and white chalk, their faces half-hidden by dusty rags: men and women distinguishable only by their eyes, bloodshot with fatigue, and by the forms of their white, calloused hands, which they would not shake with visitors. Almost every day, they scavenge from morning until sunset, amid the reek of burnt plastic, asbestos dust, and broken concrete.

For years, long before rebel troops marched over the capital in December 2024, poor displaced families and their children have come to the ruined peripheries of Damascus to collect scrap rebar, aluminium cables, and twisted pieces of iron plates. Under the Assad regime, most of these lands were no go areas. For the past four years of war, Ahmad and Basel’s families have had access under a special agreement: they would be among the many that made up Assad’s personal army of scrappers.

“The Fourth Division would grant you permission to enter here to work and sell to them,” said one of the men that gathered around us during a break from scavenging through the rubble, the face hidden by an ashy rag, “you couldn’t sell to anyone else.” rights

A scene that should haunt us all: one piece of this steel scrap – bought for a mere 500 Syrian pounds per kilo by desperate families during and after the war, with the covert backing of local warlords – may have been used to build a stadium in Brazil, the Hong Kong International Airport or Dubai’s most famous luxury hotel, the Jumeirah Burj Al Arab; it may also have ended up in a brand-new building apartment in Germany, or found its way into motorways in Romania.

Ahmad and Basel are at the bottom of a supply chain that is indispensable for ‘cleaning’ one of the dirtiest industries in the world: steelmaking.

‘Clean’ steel

Steel forms the backbone of industrial society: from railway lines and ships to the beams that support our buildings, and the weapons that can destroy them. The process of producing this durable material from iron ore, carbon, and various other metals is responsible for almost 11% of the global CO2 emissions.

In the last decade, new technologies to produce recycled steel have garnered the industry’s interest: it is cleaner and, most of all, cheaper; electric arc furnaces, under the correct conditions, consume around 70% less energy than traditional iron ore-based blast furnaces. Turkey’s producers were particularly compelled: in two decades they turned recycled steel production into the fifth largest contributor to the national economy. Turkey is now listed among the major steel producers in the world, with a steel export value estimated at $16.1 billion USD.

The issue with scrap metal, indispensable for the production of recycled steel, is that it is limited. There is barely enough of it in the world to meet the demand. As production volumes of steel are surging worldwide, ferrous scrap is now treated as strategic for the future of many national metal industries.

As the world’s largest importer of ferrous scrap, Turkey has turned it into its humble gold. Yet, not all is known about the country’s discreet sourcing network, which experts and researchers we spoke to described as opaque, unmonitored, and hard to trace.

In economies that industrialised early, scrap metal is abundant. Europe’s scrapyards are overflowing with end-of-life ferrous goods, which are the source of more than half of Turkey’s imported scrap. When the corridors of Brussels filled with whispers of a possible export ban – meant to protect the continent’s bleeding supply -Turkish companies began to look elsewhere to keep the imports flowing, sources in the sector told us. And as it happens, few events generate metal waste as swiftly as war.

We estimated that over the last five years, between 6 and 10% of the scrap recycled in Turkey came from countries we can define as in conflict: Syria, but also Libya, Lebanon, Ukraine, Russia, and Israel/Palestine.

Despite the pittance paid to vulnerable people in conflict zones to dismantle entire battle-scarred neighbourhoods, the scrap metal trade represents a $46 billion market. Because of a lack of international monitoring and an opaque supply chain, Turkey – and the world’s – hunger for scrap predictably attracts exploitative individuals hoping to bankroll their wars.

The New Arab (TNA), in collaboration with SIRAJ and El Paìs, documented the journey of steel scrap headed to Turkish mills from war-torn countries. We searched for documents in abandoned Assad-era checkpoints, sifted through tens of thousands of maritime traffic records, examined satellite images for shipments, and pieced together leads through dozens of conversations with workers and experts across multiple countries.

This year-long investigation proves that, during the last decade, roughly one tenth of Turkey’s ferrous scrap was sourced from war economies. Under Assad’s order, scrap-loaded trucks exited the country from Lebanese border crossings, to eventually turn up in Turkish private companies’ scrapyards.

Trade data show that several Turkish steel mills ship their finished products to European clients – meaning that conflict-sourced steel is most likely used across the continent.

Opaque due diligence

TNA contacted human rights officers within large European construction companies. Though they requested anonymity, they admitted that human rights abuses in the scrap metal supply chain can go overlooked within due diligence processes. They justified this by pointing to the complexities of the trade, notably its fragmented procurement and limited traceability.

Other sources from Artimet, an independent Turkish inspection company monitoring various stages of the scrap supply chain, confirmed to TNA that their quality controls consist of merely visual inspections.

Artimet representatives added that inspections would not probe how the scrap had been collected or who had profited from it. They told TNA that the end client would not care.

Many of the steel companies in Turkey declined to speak to us or ignored our requests for comment. These include Diler, Kroman, Mescier, Yazici, and Yesilyurt Demir Çelik, companies which this investigation found to be involved in procuring scrap metal from conflict countries. TNA also contacted Turkey’s Ministry of Customs and Trade, inquiring about the controls in place to detect conflict-linked scrap metal. We received no response in time for publication.

The general director of one of Turkey’s major steel companies candidly admitted, during a conversation on background, that scrap may be sourced from war-ravaged territories, including Lebanon, Israel/Palestine and Libya: “The steel of the destroyed buildings [there] will become scrap.” The company publicly declares exporting to more than 60 countries.

Many in the sector seem to be mostly clueless about the possible implications of their tainted supply chains.

The Foreign Trade Department of one of Turkey’s major scrap-dealing companies told TNA that they didn’t have specific policies in place to rule out links between imported scrap and warring factions. “We only purchase scrap from places we know and have worked with for many years,” they explained. The same scrap may then be sold to European countries like Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands.

While the Turkish scrap-dealing company claimed it was not importing scrap from Syria, they admitted to buying from both eastern and western Libya. Our investigation shows that this is not uncommon: Syria and Libya are just some of the many countries in conflict where the scrap metal trade has been exploited to feed the region’s war machine. Turkish companies are even trading with entities with which the Ankara government has been at loggerheads for years.

Israel, for instance, is among the countries at war from which Turkey buys scrap metal. It remains difficult to determine how much of this scrap originates from Israeli industrial and consumer waste, and how much comes from the devastation it wreaks upon the occupied Palestinian territories. Turkey imposed a commercial embargo on Israel only in mid-2024, in protest of its genocide in Gaza. Despite this, some Turkish media outlets reported that scrap shipments continued through third-country vessels or falsified freight documents, leading the Turkish government to sanction several ships involved. This way of dodging restrictions would be consistent with industry practices revealed by our investigation.

Trading with entities in conflict affected countries is not inherently illegal, but in some cases trade is restricted or banned under sanctions, laws or embargoes. Specifically, for cargoes of steel scrap coming from Haftar’s Libya or Assad’s Syria, the habitual supply standards and procedures are not enough, a senior researcher at the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), Blanca Racionero Gomez, explained to TNA.

“It’s not so important if you have suppliers coming from war-torn countries. What’s important is if their supply is financing conflict, is exacerbating human rights abuses and is causing environmental damage. That’s what’s important, and what needs to be addressed through due diligence processes,” said Racionero Gomez.

“Because it’s a conflict-affected area, you need to […] be more vigilant than in other areas where information is easier to access,” explained the BHRRC researcher, calling on any company downstream the steel scrap trade to be held accountable.

Syria’s 4th Division and its army of scrap pickers

Wherever Assad’s special army of scrap collectors went, only cement would remain.

Most of Qaboun, a suburb in Damascus, long contested between opposition and loyalist forces during the civil war, has been reduced to a grey wasteland of pulverised cement. There are paths to walk through the mounds and the waste is partitioned into small islands of debris. Anywhere outside these beaten trails may be unsafe: unexploded ordnance lays below the surface, sleeping but only lightly.

The horizon of desolation, sentenced by the low, uneven expanse of crumbling concrete, is betrayed by cut-outs of lush green, disorienting against the opaque haze that surrounds us. Life is flowing back in, now that the Assad forces can no longer prevent residents from returning to the hull of their homes.

As in many of the areas that bore witness to years of fierce battles, none of the buildings’ roofs remained: not because of the fighting, but because the steel rebars had been stripped from the supporting columns. Some recognised what remained of their home only by the pattern on the floor tiles, recalled Mohammad al-Imam, an activist from Daraya, another gutted town south-west of the capital, which rose to prominence as an iconic arena of civil resistance during the early phase of the uprising against Assad.

As Mohammad walks us through Daraya’s barren streets, ringed by the husks of roofless buildings, he regularly points at floors hanging in the void, pinning it on Assad’s forces: “This one was taken down, you see, look, its iron was removed – but this is not detonation, this has been taken down to take the iron.”

They wouldn’t say anything about the children; anyone could work, confirmed Ahmad’s mother, recalling the four years where they had no choice but to toil as steel pickers for the 4th Division, the Syrian military’s elite unit. Her large blue eyes gleaming over a face powdered in white dust by a day of sifting through rubble. “They used to buy it cheaply, [but sold it] expensively,” she told TNA, “it’s known.”

Formed in the 1980s, the 4th Armoured Division effectively served as a praetorian guard for the Assad family, charged with protecting the regime from internal and external threats. Over the course of the civil war, Western sanctions cut Syria off from the global financial system and the 4th Division became central to the regime’s war economy, developing into an amorphous parastate towering over strategic – and mostly illicit – businesses in Syria (such as the manufacture and smuggling of captagon).

It operated under Major General Maher al-Assad’s command, the brother of toppled President Bashar al-Assad and arguably the second most powerful man in the regime. Their intimidating checkpoints were pervasive across the country, yet the Division’s true circle of power clustered around Damascus’s peripheries.

It’s no accident that Qaboun and Daraya, among the areas to suffer the most extensive pillaging, were under the Division’s control. The scrap metal trade – mostly extracted from plundered private properties and infrastructure in former rebel-controlled areas – was one of the unit’s economic revenues.

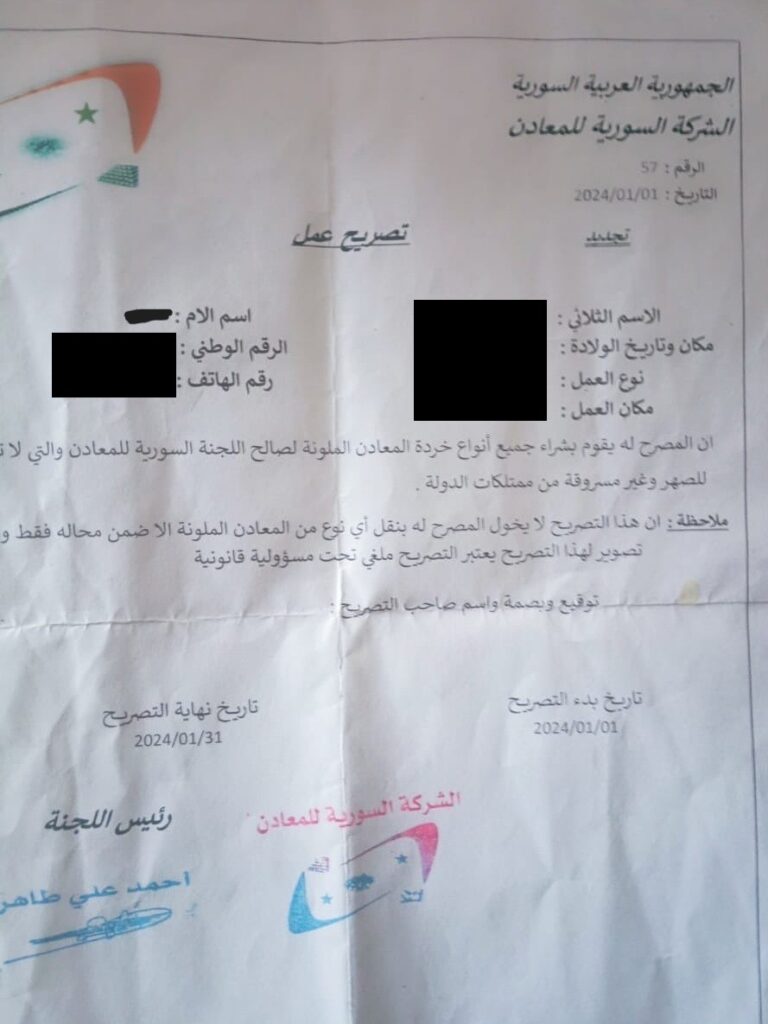

Bashar al-Assad used to layer relatives, proxies, and front companies between him and his revenue sources. The Syrian Minerals and Investment Company – a private entity founded in 2018 – worked as one of these fronts through the 4th Division.

In 2019, the Assad regime issued Resolution No. 3061, granting the company the right to import and export key materials, including metals, iron, and aluminium. The firm was in charge of issuing permits for contractors, who would purchase scrap on its behalf.

Two years after its establishment, it had already been sanctioned by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) for its connection with businessman Khodr Ali Taher, a man with long-standing ties with the 4th division. Taher was also known as the “Prince of Crossings” in national media, for the ease he would be wending his way across regime and rebel-controlled areas.

Western sanctions and arrest warrants hang over the heads of many businessmen and military commanders who were part of the 4th Division’s network that capitalised on the bloody scrap metal trade.

Previous investigations have already exposed how the Assad regime and its cronies had been profiting from looting iron scrap from opposition areas that would feed the country’s steel plants. Yet little is known about how scrap has turned into a profitable export commodity sold to Turkish companies; a discreet trade that lasted years, while Turkey-backed opposition militias and Assad’s army have been battling each other.

Burn the evidence

The road winding through the Masnaa-Jdeidat Yabous passage, connecting Beirut to Damascus, is lined with Bashar al-Assad’s faces. Most have been removed from billboards and posters, but those that could not be taken down have been crossed out.

Next to the traffic highway, amid sallow mountain ridges, vehicles laden with goods and people thread the main Beirut-Damascus crossing. An unassuming and doorless single-storey structure stands on the side of the road. Another of the President’s crossed-out faces, plastered over the outer wall, greets passersby.

The place is trashed, full of torched, half-burnt documents. Perhaps, as the news that Assad’s forces were crumbling, someone returned to the checkpoint in a bid to destroy evidence of the regime’s activities, a story often heard in Syria after December 8, 2024.

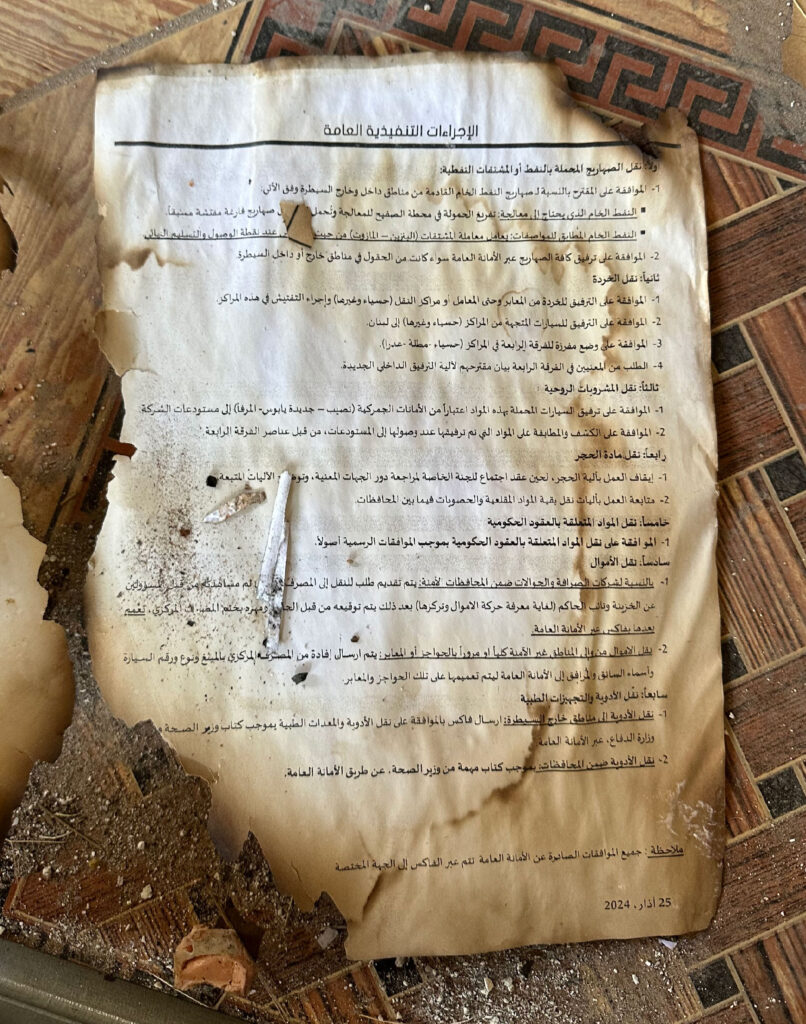

This was a 4th Division checkpoint located near the Yafour Bridge, in a rural area west of Damascus, along the M1 highway to Beirut, just 20 kilometers from the Lebanese border crossing. One of the many under the 4th Division’s sway, racked up across major domestic and international highways, part of a strategy to take control of vital export routes.

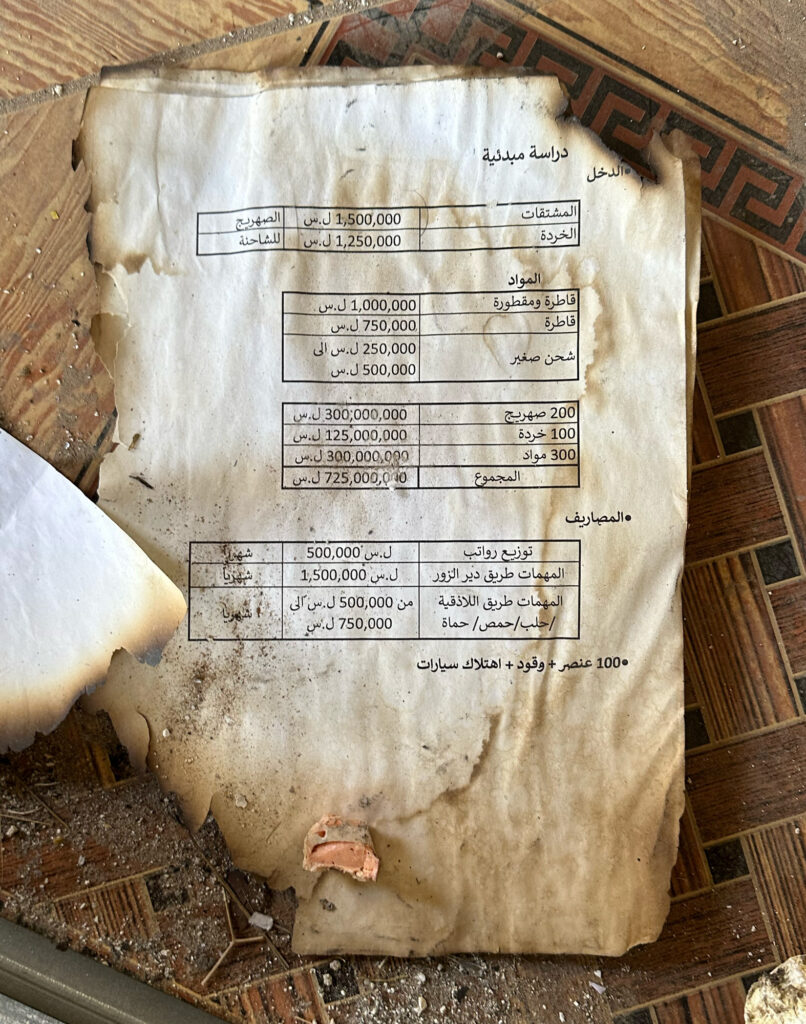

When Assad’s many faces still towered over these lands, this checkpoint was expecting to see a hundred scrap metal trucks cross in just one month. (We can’t know when exactly – part of the page was burned. The date was lost). Each lorry had to pay its due, the amounts spelled in black ink in an exclusive “pre-feasibility study” we photographed. In just one month, the 4th Division was planning to extract a total of roughly 125 million Syrian pounds [$9,615] from 100 scrap metal trucks en route to Lebanon.

For years, this unremarkable checkpoint quietly collected proof of a major export route for scrap pillaged by regime forces and its transfer to Lebanon. Scrupulous workers amassed records detailing the passage’s ins and outs. Most of them are lost in the arson. But the few pieces we were able to photograph provide insights into how Assad’s economic machine was moving metal scrap and other goods across the country. The documents also offer a rare glimpse into the hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue likely generated by this checkpoint. Some of the most recent records date back to September 2024.

On 10 April 2024, the Yafour Bridge checkpoint received a fax from another crossing. “For your information, no commercial convoy crossed the post.” Written in a few lines of black printed ink and signed twice, the headed notification passed from Colonel Louay Ahmad Habib, who was in charge of the Manbij crossing (also known as al-Tayhah crossing) between the regime and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), to Major-General Ghassan Bilal, Maher al-Assad’s right-hand man. Bilal is also on the EU and US sanctions lists for his affiliation with the Assad regime. By the time we found the document, he had likely already fled.

Documents we photographed confirm that scrap trucks, given their high value, were escorted by units of the 4th Division from the industrial centres of Hasiya, al-Matalla, and Adra across the border to Lebanon.

“They [i.e. the 4th Division] would give you permission to transport the materials to the factory. If you didn’t inform them, the vehicle, materials, and driver would be seized. This is the rule,” said a scrap reseller we talked to in Damascus.

According to the documents, the entity in charge of authorising the deployment of the 4th Division to escort scrap trucks was the Syrian Presidency’s General Secretariat, headed by Mansour Fadlallah Azzam, who is under Western sanctions for his role in the violent repression of the Syrian uprising. He was also Minister of Presidential Affairs between 2009 and 2023. The current whereabouts of Azzam are unknown.

Across the Syrian-Turkish border

The Masnaa passage isn’t the only corridor we were able to identify. Although to a lesser extent, evidence suggests that another crossing enabled metal scrap exports to Turkey.

Under a makeshift tent, nestled by mounds of grey waste and twisted metals that rest along the road connecting the small village of Killi with Idlib, in northern Syria, a collector we interviewed in a crowded scrapyard recounted the days during the war when larger players selling to Turkey would buy material from these very piles.

“This scrap iron comes from homes, and we buy it from local collectors” he explained. “The [local] iron companies buy it from us, export to Turkey, and also sell scrap within the liberated areas (i.e. areas under opposition control before Assad was toppled).” At a distance, young men press large chunks of iron scrap inside a deafening machine.

Turkey’s trade data indicate that, between 2021 and 2024, over 200 thousand tons of metal scrap entered the country from areas under rebel control in northern Syria. Most transited from the Bab al-Hawa border gate, which was manned by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the hardline Islamist paramilitary group which is leading the new Syrian administration.

The Idlib deputy governor, Qutaybah Khalaf, told TNA that, over the years, Turkey-bound scrap may have passed through the rebel-controlled border crossings. But he described this trade as “private work” that saw no involvement from local authorities.

However, experts do not discount the likelihood that entities loyal to the regime could have collaborated with opposition forces in facilitating the scrap trade.

“Even for the captagon trade, for example, there were some people inside opposition areas who were working with the 4th Division and Hezbollah,” said Ayman Aldassouky, a researcher at Syrian think tank Omran for Strategic Studies, who focussed on the 4th Division’s economic network.

Nonetheless, statistics show that only marginal amounts of scrap flowed to Turkey via Syria’s northern land crossings. Turkish customs data may capture just part of the trade, and the 4th Division may as well have used those routes to smuggle scrap directly. But inland roads were fraught with opposition factions, which likely made Lebanon the main route – an off-book trade some deny exists, given the lack of official records. Were it not for a small anomaly in those same data.

The Lebanon route: numbers don’t add up.

There is no trace of the trucks loaded with metal scrap flowing in through the Masnaa crossing in Lebanese public statistics. Yet something may give it away: the quantity of scrap metal generated locally seems not to keep up with the export volumes listed in national and international statistics. An unregistered source of metal scrap, slipping through the border, could explain the irregularity.

Most Lebanese workers and companies we spoke to deny dealing directly with Syrian scrap, but it seems no secret that Lebanon is a corridor for this trade. A source from the city of Baalbek – a known hub for smuggling, northeast of Beirut – with personal knowledge of these networks, reported they were offered Syrian steel for a construction project by a contractor once.

Antoine Srour, a scrapyard owner in Beirut, explained to TNA that, in the aftermath of the latest Israeli war on Lebanon, “metal from the South all went to traders from the South. And metal from Dahiyeh [i.e. Beirut’s southern suburbs] all went to traders down there, to Shatila in particular. […] Northerners […] profited from Syrian metal.” In early 2025, media reports described residents of the marginalised northern area of Wadi Khaled, near illegal border crossings, complaining about convoys of trucks entering Syria loaded with cement, fuel, and other Lebanese goods, and returning with vegetables and scrap metal. Detection would be hard: smuggled goods are often mingled with Lebanese ones, said the anonymous source.

In the Bekaa valley, tribal networks smuggle anything that has value – weapons, drugs, and stolen goods – in collusion with Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shia Islamist political and military group.

The anonymous source doesn’t believe the traders who denied having dealt with Syrian smuggled metal scrap are telling the truth. Hezbollah has had longstanding ties to Assad.

“Now, after Bashar al-Assad’s fall, I’m not sure how things are – they’re still bringing in stuff and taking stuff out, but it’s not the same as it used to be,” commented the source, “back in the day, when Hezbollah was in Syria, […] if you had permission from Hezbollah, you could just walk in and out whenever the hell you wanted without even an ID.”

International sanctions made the use of ports for exports difficult in Syria, with only a handful of vessels permitted to dock, explained researcher Ayman Aldassouky. This turned Lebanon into the perfect backdoor for the regime, allowing it to save face while doing business with an enemy in war such as Turkey.

Scrap iron and steel are Lebanon’s fourth largest export. UN Comtrade statistics show that over 2 million tons of iron scrap have left Lebanese ports headed to Turkey since 2013. Part of this may have consisted of re-exports from areas under the Assad regime’s control in Syria. The main customers of Syrian scrap exported through Lebanon were reportedly Turkey, India, and the United Arab Emirates, Ayman Aldassouky told TNA.

The other part comes from local production. Here too, waste pickers are often minors, many are Syrians. After Israel’s latest war on Lebanon, districts hit by airstrikes are also turning into a source of scrap, according to locals we talked to and media reports. With no active steel recycling mills in the country, a large part of this locally collected scrap is recycled in Turkey.

The Lebanese Ministry of Economy and Trade did not provide comment to TNA in time for publication.

Scrap fleet

Iskenderun, southeast Turkey, is a city tailored to industry: the outer roads are jammed with trucks, factories and their piers flank the highway, and a smoky chimney is always fixed on the horizon. Here, bulk ships carrying scrap from war-torn countries have been docking at the steel companies’ private piers for years.

In the Turkish companies’ furnaces, where a soup of metals and alloys is cooked at around 1,600 °C, the trail of the iron scrap’s origins melts away. Turkey’s finished steel ends up all around the world. Major destinations include Spain, Greece, Italy and Romania, but also Yemen, Egypt, Morocco, and Iraq.

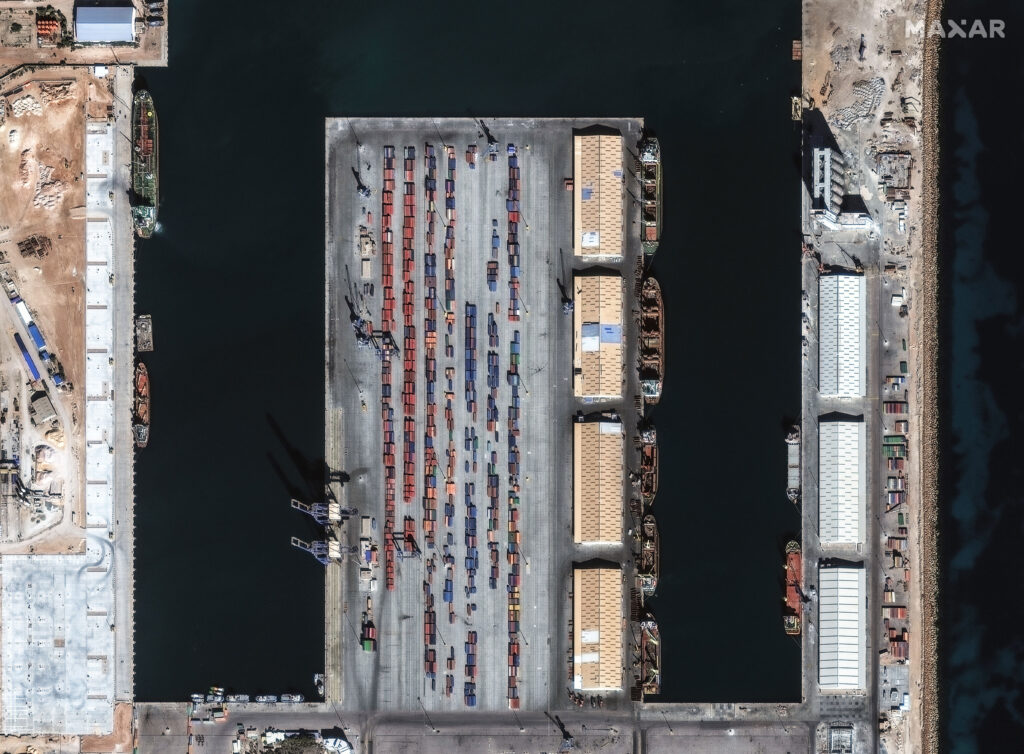

Based on data provided by MarineTraffic, a ship tracking and maritime analytics provider, TNA analysed tens of thousands of entries for bulk carriers docking at Turkey’s various ports. As none of the governments of the countries involved in this business would grant us detailed access to customs and trade data, we verified their cargo through satellite images obtained through Maxar and Planet. We could verify at least forty ships in 2023 alone: not only scrap-loaded ships sailing from Lebanon, but also vessels departing from ports in Libya, Russia, Ukraine and Israel/Palestine. In most of these countries, Turkish companies purchased scrap metal from both parties to the conflict.

What we identified is likely to be only the tip of this unknown trade, a fraction of the number of vessels whose tainted cargoes help bankroll conflict internationally.

Libya: rebuilding an army ‘scrap by scrap’

Following the toppling of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, Libya has been mired in conflict for around a decade. Despite the signing of a fragile ceasefire agreement in 2020, the country remains politically and militarily torn between two competing powers: the UN-recognised Government of National Unity (GNU) in the west and the so-called Libyan National Army (LNA) led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar in the east.

In mid-April 2023, a bulk carrier going by the name Nezha, approached the port of Benghazi in eastern Libya to fill its cargo with scrap. Two weeks later, it would unload the scrap at the Iskenderun pier of US-sanctioned MMK Metalurji, the Turkish subsidiary of Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works, a Russian steel manufacturer that ranks among the largest in the world. The Nezha was previously identified as having violated EU, US, and UK sanctions by docking at ports in Russian-occupied Crimea in 2019 and subsequently had its license revoked.

We sought comment from MMK Metalurji but received no response in time for publication.

In the last decade alone, Turkey imported over 3 million tons of scrap steel from Libya, according to UN Comtrade data – more than even petroleum.

Although official data do not specify which of the two rival authorities the exports derive from, satellite images show that in recent years one of the most active ports for loading scrap has been Benghazi, in Haftar’s zone of control – a confirmation of Turkey’s most recent rapprochement with the rulers of eastern Libya. All the while, Ankara continues to support the GNU in the west, both militarily and politically.

According to human rights’ groups and the UN, forces under Haftar’s control have committed “horrific crimes” – including torture, sexual violence, and forced labour – against Libyans and migrants alike. Forces under the GNU command have likewise been accused of gross human rights violations.

Experts highlight that scrap metal export revenues have helped fund the rearmament of General Haftar’s forces, as they fight against their rivals in the west of the country.

“They started […] in the mid-2010s. Haftar used the money from the scrap to rebuild his army. Used the scrap from war-devastated Benghazi. Then even when Turkey intervened against Haftar, [he] still continued selling his scrap to Turkey,” said Tarek Megerisi, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Despite a Libyan ban on scrap exports, imposed to support domestic steel production, cargoes of steel waste continue sailing from all ports.

TNA reached out to the LNA as well as longtime spokesperson Lt Col Ahmed al-Mesmari for comment but they declined to respond.

All the ships loaded with metal scrap sailing from ports in Ukraine, Russia, Israel/Palestine, Lebanon and Libya that this investigation was able to identify, bear the risk of being associated with conflict financing and human rights violations.

European and Turkish companies downstream the supply of this trade cannot erase this risk either, explained Racionero Gomez from the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Directives from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and UN guiding principles set important benchmarks for companies, but even if corporate policies align with them, “their requirements and stringency vary a lot and one cannot fully trust standards blindly,” said Racionero Gomez, “we need to remember that the duty to protect human rights is on states, so we need regulations as well. We shouldn’t just put all the emphasis on standards.”

Rubble and mortar rounds with no end in sight

That day, Basel and Ahmad’s workday ended early – the sun was already setting over their rubble realm. They spent the remaining hours lingering unpredictably, waiting for the middlemen’s truck to come and pick up the scrap. But the truck would never come; the adults hid the bounty in a big hole, trusting no one would steal it before their return tomorrow.

All of them had small red veins in their eyes. From the 35-degree September sun, from the haze of dust rising from the rubble, or perhaps from the black smoke billowing from the bonfire lit to strip the plastic insulation from copper wires. “They’re more valuable like that,” they explained.

“Are there bombs here?”

“There’s plenty,” Ahmad quickly replied. He wanted to show us one, but we convinced him to desist. His uncle was digging and a rocket exploded on him, the families would later tell us.

Buyers would pay less for scrap originating from war zones, as there might be a chance that bombs and ammunition would show up in their load during inspections at border checks. There is no cheaper scrap than the Syrian one.

Our presence agitated the two kids. In the deserted yard shadowed by once-lively apartment complexes in a suburb of Damascus, they started playing with the shell of an improvised explosive device. With a twist of his arm, Basel threw it in a perfect arc two metres away, back into the rubble where it came from. Earlier that day, standing over a pile of rubble as kings, Basel and Ahmad had claimed proudly that they knew how to stay safe from war’s leftovers.

Assad or not, their lives haven’t changed much. They had been coming here since they were five or six, almost every day from dawn till dusk.

Ever since the HTS-led government has taken over, many of the men of Assad, involved in the scrap metal monopoly, have fled; some of them made deals with the new ruling forces and were reintegrated. The offices of the Syrian Minerals and Investment Company are open again, nestled in the industrial city of Adra. TNA contacted the company, seeking comment on their activities under the Assad regime and on whether scrap-related controls were introduced under the new administration. We received no response in time for publication.

Last June, the new rulers in Damascus imposed an export ban on scrap metal – now valuable for the country’s reconstruction – though it’s hard to say whether it will be respected: provisional statistics for 2025 reveal that minor exports of scrap have continued until a few months ago.

When contacted for comment, Syria’s Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour directed TNA to regional directorates for further information. Neither the Syrian Ministry of Finance nor the General Customs Directorate replied to our request for comment.

The people managing the scrap trade in Syria may change; Ahmad, Basel and their families will not. Tomorrow, they will still be here, together with the unexploded munitions, the broken cement, and the scrap for which they are paid only 500 Syrian pounds per kilo.

* Pseudonyms have been used for these names for security reasons.

This investigation was developed with the support of JournalismFund Europe.

Additional reporting on Lebanon: Richard Salame.

Animated infographic on the Nezha vessel: Ornaldo Gjergji

Fact-checking and copyediting:

TNA Investigative Researcher/Journalist Jonathan Cole.

Commissioning, editing and supervision:

TNA Investigative Editor Andrea Glioti.