In Tripoli city, north of Lebanon, home turned into a prison for Amina, a Syrian refugee who chose to go by a pseudonym, after the Lebanese General Security confiscated her passport, and the passports of her family members. The nine-member family was ultimately trapped at home, and their life stopped moving; Amina’s husband, and her eldest son, could no longer leave home to work, while they all had to sneak out to run daily errands.

Amina, her husband, and five children arrived in Lebanon in 2012, seeking medical care for her husband who was injured in a bombing frenzy near Damascus.

Amina and her family are registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Beirut, and their basic needs, such as housing; food assistance; and the husband’s treatment are mainly provided by charities. They had no idea, however, that they needed to renew their Lebanese residence permits, which they learned of when Amina’s husband was notified of a non-renewal fine of US $800 (1,760,000 Syrian Pounds). By the time he managed to secure the fine’s money and went to pay it, Amina’s husband received a deportation order from the General Security.

During her stay in Lebanon, Amina gave birth to two other sons. One was born with a congenital heart disease and needed treatment that was expensive in Lebanon. Considering that medical care was free in Syria, the mother set her mind to travelling back with her two younger sons. “On the Syrian border post, the Lebanese authorities gave me a pink form, which was supposedly to help me legalize my status in Syria, except that it contained an order of no-entry to Lebanon because I overstayed my residence permit’s duration,” Amina says.

In keeping with the regulations enforced by the Lebanese government since early 2015, Syrian citizens adhere to certain entry procedures, whereby they must obtain the border authorities’ approval for entry and provide relevant supporting documents. Syrians are then granted permits of various stay periods. In cases of transit through Lebanon; medical visits; or an appointment with a foreign embassy, for instance, Syrians are allowed a 24 hours stay, which extends to a whole year for residents; university students; and the holders of a work authorization. It ought to be noted that these regulations have been declared illegal and annulled by Lebanon’s State Shura Council under Resolution No. 412/2017-2020, for being passed by an incompetent authority.

Amina tried to return to Lebanon three months later, having completed her son’s treatment in Syria. It was then that the Lebanese Border Guard told her she was denied access, and the reason, to her shock, was the non-renewal of her Lebanese residence permit. She had no other choice but to return to Syria once again. Amina eventually returned to Lebanon through her husband’s Lebanese personal connections, who helped him send an official letter to the General Security on the border post. Upon entering the Lebanese territories, the authorities confiscated Amina’s passport, and those of her two sons. She was notified of the need to refer to the General Security Office (GSO) in Beirut.

At the office in question, officials asked her to return 15 days later. She did, and again she was turned down. Amina, for quite a while, kept showing at the GSO, until finally one employee told her to never return, or otherwise he would arrest her.

This is the story of many Syrian refugees in Lebanon, whose life has stopped because their official documents, particularly passports; identity documents; and residence permits are seized by the General Security. Refugees thus have limited mobility, within Lebanon, while not allowed to go abroad. In addition, they are deprived of their right to seeking job opportunities, and registering vital events at the Civil Registry. Syrian refugees cannot record marriages; or divorces; or even births.

Playing on Terminology

It was the shared terrain between Syria and Lebanon why scores of Syrians living on the border strip flocked into Lebanon as combat escalated.

Compared to its per capita, Lebanon has hosted the largest number of Syrian refugees since 2011. And because it is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Lebanon has enforced no laws to protect refugees’ rights, who are usually stripped of their legal status as refugees, and are rather referred to as internally displaced people (IDPs). By opting for one term instead of the other, the Lebanese government manages to escape obligations it must adhere to should it recognize people it hosts as refugees. The latter are not offered a resettlement; or any of the other rights granted to citizens, including healthcare, education, and work. The distinction between the two legal terms is central; unlike refugees, IDPs have not crossed a border to find safety, and they are on the run at home. For their part, refugees are people who have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country.

According to Access Center for Human Rights, like Amina, 41 Syrian refugees in Lebanon were subjected to civil documents confiscations in 2019. In three of these cases, group confiscations were committed against civil society organizations employees. An additional 26 cases were documented by the center between early 2020 and 15 October, four of the victims were civil activists. Out of the whole, 22 of the people subjected to such seizures were registered with the UNHCR, and other 13 have entered Lebanon legally.

As might be expected, seizure of documents denies refugees their right to movement within Lebanon, or travelling abroad; making a living under their poor economic conditions; or even filing civil registration requests, such as registering marriages and divorces, or adding newborns to civil records.

Compared to its per capita, Lebanon has hosted the largest number of Syrian refugees since 2011. And because it is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Lebanon has enforced no laws to protect refugees’ rights.

The confiscations committed by the local authorities are a blatant violation of human rights, well-established in multiple international conventions, particularly the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Founded in 1921, the Lebanese General Security Directorate was called the “first bureau.” Formally, it is one of the agencies affiliated to the Ministry of Interior, and municipalities, while it is the chief agency to handle refugees-related legal affairs in Lebanon.

“Those with reported offences, or working without ‘an authorization,’ are at the risk of having a deportation stamp on their official documents, when arrested by a checkpoint, or during a visit to the GSO. Most of these deportation orders are not implemented, however, because of the pressure imposed by human rights organizations on the Lebanese authorities,” Nabil al-Halabi says, a Lebanese lawyer and the director of the Lebanese Institute for Democracy and Human Rights (LIFE). So, in most of the cases discussed here, people have to tolerate the victim/offender duality. Refugees are often coerced to breach the law due to such resolutions, which are in themselves a violation of local laws, and Lebanon’s international obligations. Deprivation of legal status makes refugees vulnerable, and an easy prey for the security checkpoints, as it allows for robbing them of their basic rights; denies them legal access to residency; and turns them into outlaws. Once these people leave Lebanon; they will not be able to return in any way.

No Syrian refugee is spared this deadlock. Amounting to 879,529 registered persons, according to UNHCR figures, Syrians in Lebanon, who primarily reside in areas across Beqaa and northern regions, constitute 15.8% of the total number of Syrian refugees hosted on the world’s level.

Confiscation Consequences

The Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2017-2020 (LCRP), the UNHCR reports, seeks to provide a framework for an integrated humanitarian-development response in which the needs of the refugees are met– to the extent possible, based on national laws and policies.

Despite the plan, Amina’s rights to her basic needs, and to reclaiming her confiscated official documents are nothing but a wish, she hopes will be fulfilled sometime soon.

In 2020, Amina said, “we were asked to refer to the Amioun Municipality, with our children and their documents, for there were instructions to deport us to Syria. We were also to pay a fine of 3 million Lebanese Pounds (LP) on behalf of my eldest son, who is 20-year-old.” There, the family fingerprinted the deportation order; their civil documents were confiscated; and only their expired passports were returned.

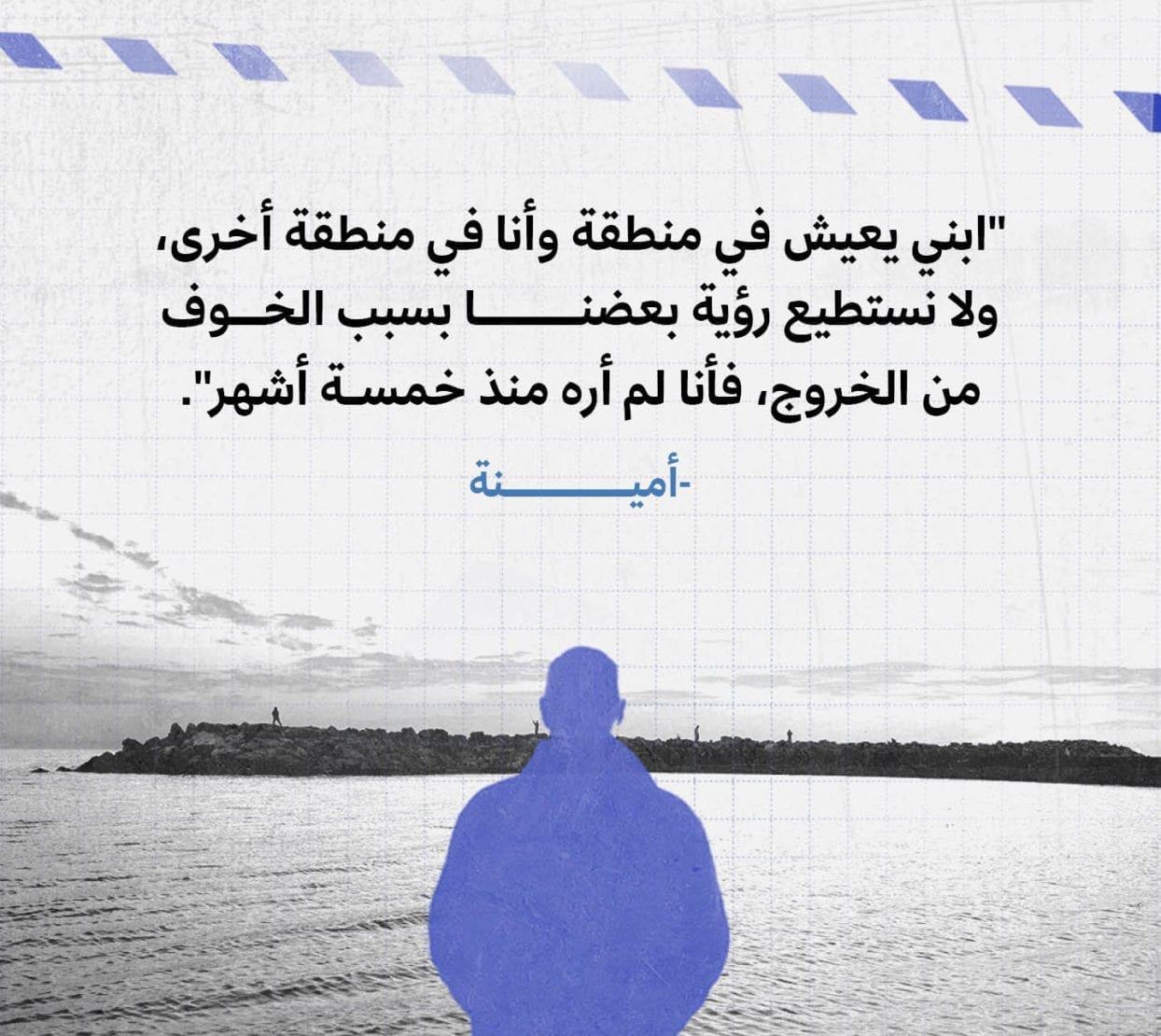

The family reached out to the UNHCR, which informed them to change their residence place. After they did so, Amina’s husband lost his job, and her eldest son, who got married and moved to live in another house, was no longer capable of working because his identity document was in the hold of the General Security. “We live in different areas, my son and I. We cannot visit each other for fear of leaving home. I have not seen him in five months,” Amina added.

Unable to retrieve her confiscated passport, nor those of her family, Amina missed the chance of traveling to Turkey in 2015. From Turkey, she intended to head to Europe as many other Syrian refugees did back then. She said, “my son and husband used to work, and now both are unemployed. My son was even offered a job opportunity at Tripoli Port, but he ended up losing it for not having an identity document.” Today, the family has no source of income, and lives in a 30-meter-room—actually a basement in a residential building. They were offered the room in return for tending the building’s door and cleaning its entrance.

According to the UNHCR in Lebanon, refugees face increased protection-related risks, given their lack of legal residency. They are vulnerable to arrest; deportation; eviction; sexual violence; gender-based violence; and child abuse. Furthermore, there is an extreme shortage of basic assistance, particularly in the fields of healthcare; shelter; and sanitation.

The confiscation of documents’ biggest loss, however, was Hassan Ahmad’s, a 28-year-old Syria refugee, who also chose to go by a pseudonym. He failed to register his marriage, and his son’s birth, at the Civil Registry. Hassan’s toddler is now more than a year old, and is stateless. In 2019, Hassan, who is a Syrian army defector, sought to legalize his status and renew his residence permit through the sponsorship system (Kafala). He also paid 900,000 LP ($600 at the time), but the General Security seized his documents, and instead gave him a deportation form, claiming he entered Lebanon illegally. Hassan so far could not recover his documents.

Hassan got married and had his first son while still attempting to retrieve his confiscated documents. He was asked to pay 400,000 LP ($265) in exchange for his documents, and the General Security told him he must leave Lebanon once he is delivered the documents back.

Hassan hopes to go to Erbil, in Iraq, but he fears the consequences of the journey. He might be “denied entry.” Such growing concerns are making the thought of travelling abroad a difficult thing, let alone making the decision.

“Neither my marriage, nor my son’s birth, are registered. My wife also entered Lebanon illegally. I dare not move around in Lebanon; I am scared the authorities might deport me to Syria for being an army defector,” he says. Hassan contacted organizations concerned with Syrian refugees’ affairs, including the Norwegian Council, but all his efforts were to no use. He even had an appointment with the protection department at the UNHCR, which was ultimately postponed due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

450 Cases of Confiscated Documents

The refugees’ failure to obtain official documents is a major barrier to accessing basic and simple services, and may even hamper their daily activities. Among many others, there are as many as three distinct reasons for the unlawful confiscation of civil documents; some people’s documents are seized during arrest; others’ documents are withheld either during the renewal of these documents; or at hospitals, when refugees cannot afford to pay the cost of their patients’ treatment.

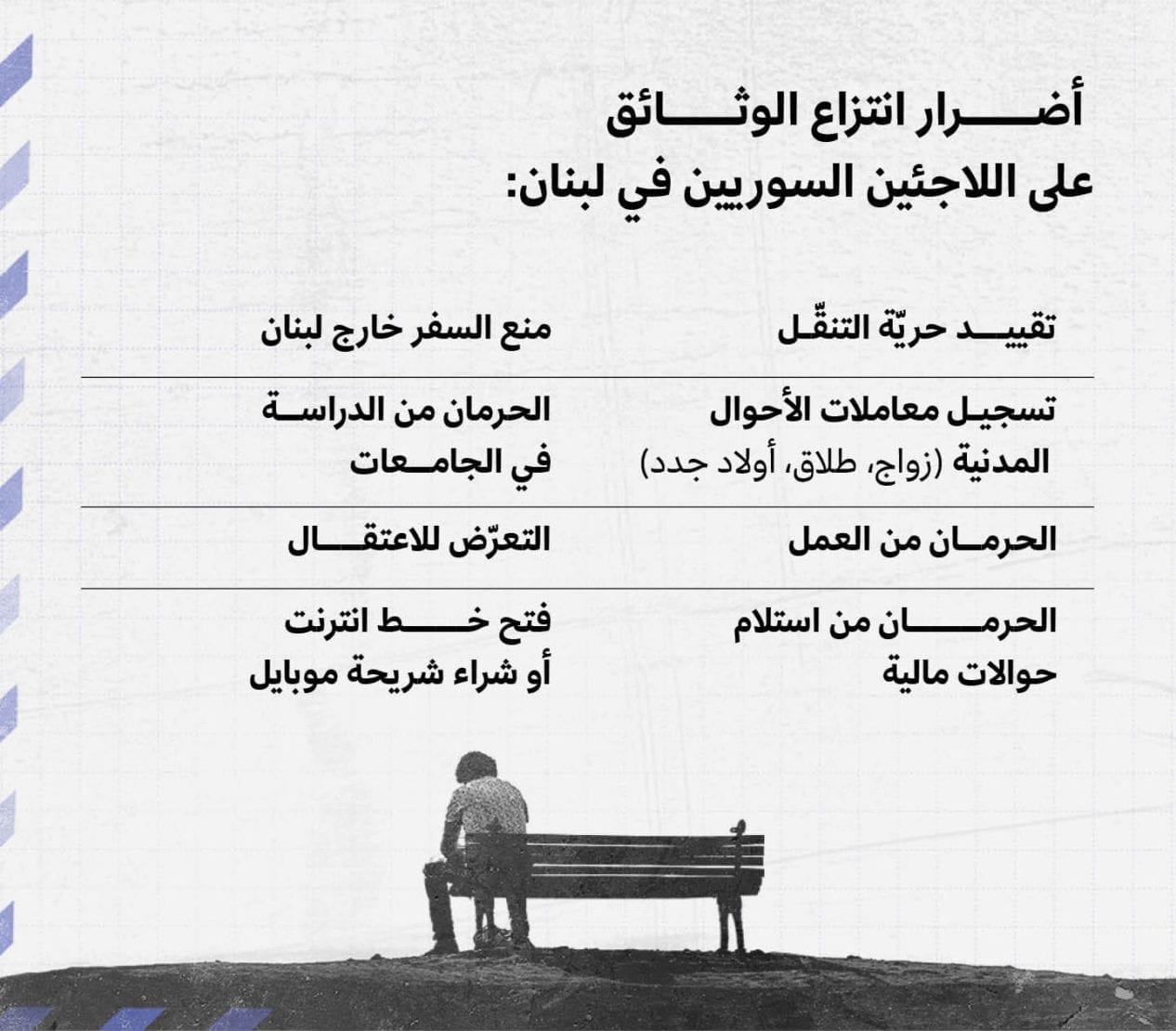

When Syrian refugees’ official documents are confiscated in Lebanon; they tend to suffer these consequences:

Arrested

Denied freedom of movement

Dined travelling abroad

Denied the registration of vital events, such as marriages, divorces, or births

Denied seeking job opportunities

Denied university education

Denied receiving remittances

Denied obtaining internet services, or a sim card

The Lebanese authorities embarked on two arrest drives in Arsal camps, in September 2014. They arrested a total of 450 Syrian refugees, over two stages and on the pretext of “terrorism”. All the detainees were subsequently, however, gradually, released, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).

Among those arrested were the brothers Maher and Muhannad, who lived in the Baalbek area. In detention, Maher claimed being subjected to beating and torture. As a result, he developed spinal disk problems, and could no longer work. After Maher and Muhannad were finally vindicated, the military seized their identity documents and released them. “The army told us to refer to the Arsal Municipality to retrieve our documents. We went there only two days later, but the municipality denied having the documents,” Maher says.

For months, the two brothers sought the municipality, and they achieved nothing every time. In the end, one employee told them: “You better forget about those IDs,” indicating that they might have been lost somewhere between the military, the General Security, and the municipality. Maher communicated with several concerned organizations, including the UNHCR. He had an appointment arranged with the latter, which was to offer him assistance because his health deteriorated severely, and he could not work. This attempt failed too, given the pandemic’s spread.

The confiscation occurred in 2014. Since then, Maher got married and had children, but was unable to register his marriage, or add his children to the civil records. Concerned organizations intervened, but still failed to help Maher do the registration, since he needed additional documents from Syria. He could not obtain the requested documents because there was no way he could return to Syria, while a checkpoint of the Lebanese military stood between him and the Syrian Embassy in Beirut. The said checkpoint was set up at the entrance to the Syrian embassy’s area, and it frequently harassed the refugees approaching it.

The two brothers stressed that it was the seizure of their identity documents that they could not obtain passports; or refer to the UNHCR; or even seek job opportunities. Without identity documents, they cannot navigate the streets policed by security checkpoints.

In a written response to the investigation team, the UNHCR said that “it supports the General Directorate of General Security (GDGS), providing it with equipment, software, and centers’ renovation to increase the directorate’s capacity to process Syrian refugees’ residence renewal requests. It similarly supplies the offices of the Personal Status Directorate (PSD), across Lebanon, with equipment and personnel to help the GDGS accommodate further requests of civil registration filed by refugees.”

The UNHCR added that, through its partners, it provides legal aid, including counseling and representation, and organizes awareness seminars and campaigns to enhance refugees’ knowledge on how to obtain legal residence permits, and civil documents to certify births; marriages; divorces; and deaths that occurred in Lebanon, and access procedures related to family affairs; domestic violence; civil or administrative disputes. Moreover, the UNHCR supports refugees as it conducts birth registrations on their behalf, at the foreigners departments of the PSD, while it also accompanies groups of refugees to the GSO to renew their residence permits.

Also with partners, it presents refugees individual legal advice on registering births, marriages, and deaths, and offers immediate assistance to families to register their children at the PSD and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In some particular cases, it even helps refugees obtain documents from the Sharia Courts, which confirm the children’s family lineage. The assistance it often offers includes obtaining retroactive evidence of marriages for those who have married informally earlier on, in addition to documenting marriages, and deaths.

“Voluntary” Return to Syria

The issue in question is not the withdrawal of documents, but it is rather deliberately keeping those documents in the authorities’ custody for extensive periods, for years at times, particularly if a security report is filed against Syrian refugees. In these cases, the General Security considers these people to be opponents, who want to travel abroad, and recount what they have been through in Lebanon. This is a security coordination process between the Lebanese authorities and the Syrian regime seeking to impede the lives of these refugees; make them miserable; and ultimately force them, in an indirect manner, to return to Syria, under the so-called “voluntary return,” the Lebanese lawyer Nabil al-Halbi says.

The express purpose of confiscating documents is to impose restrictions on Syrian refugees in Lebanon, according to lawyer al-Halabi. “Four years ago, the Norwegian Foreign Ministry made a statement, demonstrating how the Lebanese authorities are preventing Syrian refugees from traveling to Norway after they had been offered the opportunity to resettle in a third country. Similar restrictive measures were applied to other refugees who were not allowed to travel to Canada or other countries.”

Violations of the Law

Even though the Lebanese local laws lack legal texts that regulate the confiscation of official documents belonging to persons residing within the country’s boundaries, the Lebanese authorities should comply with their human rights obligations, which are grounded in equally important international conventions and treaties, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In the latter two conventions, several articles protect people’s right to freedom of movement and legal status, regardless of their place of residence; or the reasons that led them to leave their country of origin in the first place.

Furthermore, the nine core international human rights instruments grant people the right to nationality, as a non-derogable right, which cannot be abolished or suspended by the government, not even during emergency situations. Stressing this right, Article 6 and article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights respectively state that “everyone shall have the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.”

Individuals acquire legal recognition, when vital events are registered at the concerned departments, such as births; deaths; marriages; and divorces. This is a fundamental human right, through which individuals gain access to nationality, or legal residency, and the corresponding rights, privileges and responsibilities as citizens in a given country. Based on this, the confiscation of civil documents is a violation of these rights, because these proceedings prevent people from conducting necessary civil status registrations, and deny them access to humanitarian aid and basic services, including education; healthcare; and opening a bank account. Worse yet, these confiscations increase the risk of statelessness.

The seizure of documents also affects individuals’ right to unrestricted mobility, recognized by Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, whereby “everyone has the right to freedom of movement; to leave any country, including his own; and to return to his country,” and the first clause of Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, by which “everyone lawfully within the territory of a State shall, within that territory, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose his residence.”

UNHCR’s Role

Of the 41 cases of document confiscations recorded by Access Center for Human Rights, 37 people are officially registered with the UNHCR, which failed to intervene, according to the refugees interviewed by the investigation team. This lack of action on the part of the High Commissioner is at odds with its obligations towards registered refugees, since registration entails protection.

“The situation spirals when the Syrian refugees subjected to documents seizure are not registered with the UNHCR. If so, the organization’s Protection Office cannot intervene and is not granted the UNHCR’s authorization to react, even when human rights organizations transfer refugee cases to the UNHCR,” lawyer al-Halabi said.

Al-Halabi urges the international community, and the UNHCR, to address the confiscation of documents, including the cases of refugees who are not registered with the High Commissioner. The UNHCR must act on the situation, and follow up on the matter with the Lebanese authorities, since these seizures have an impact on all rights, including the implied rights to freedom of movement, and work, particularly because the documents are often withheld for an indefinite period of time. “Should the confiscations the Lebanese security agencies embark on be considered legal entitlements, the confiscation’s duration must at least be clearly defined,” the lawyer said, or otherwise, the confiscation will be an “abuse of this entitlement.”

What the UNHCR can do is to set up a protocol with the Lebanese General Security to process the files of persons whose documents are seized, while they do not have security-related issues. People in this group can at least be granted a six-month residence permit, till their situation is resolved, Muhammad Araji said, a Lebanese lawyer and the CEO of Access Center for Human Rights.

“We live in different areas, my son and I. We cannot visit each other for fear of leaving home. I have not seen him in five months,” Amina added.

The UNHCR, Araji said, must conduct a field survey to identify the number of Syrians who hold a residence permit, and those who have an illegal status, to tackle both groups’ problems in cooperation with the General Security.

In early 2020, the UNHCR reported as its propriety, “ensuring access to protection, temporary legal stay and birth and civil status documentation for refugees, and their protection from refoulement.”

As mentioned above, the investigation team requested the UNHCR’s comment with respect to the confiscation of documents; the steps it takes to address this violation; the measures it adopts to ensure that persons whose documents are seized are capable of conducting civil status documentations, and have proper access to hospitals, and the campaigns it launches with the Lebanese government to make certain that international laws are applied.

The UNHCR said, “should refugees report similar practices, the legal programs, for instance, the UNHCR will intercede with the Lebanese authorities. Responding to the High Commissioner’s unremitting advocacy efforts, the General Security issued an internal memo, demanding that all its affiliated centers refrain from taking originals of documents, such as identity documents; passports; civil extracts; and entry and exit visas, from Syrians renewing their residence permits. Instead, those centers are to ask for scanned colour copies of the original documents. The memo, thus, ensures that no documents will remain in the hold of the General Security, even when renewal requests are denied, while offering a solid legal ground for intervention should the confiscation violations continue to occur.”

The UNHCR said that it engages in continuous dialogue with the Public Security Directorate, on the central and local levels, to address any inconsistent practices and ensure they are all in harmony.

Concerning its measures, the UNHCR said that, “when documents are seized by individuals, say landlords, employers, etc., or private entities, including hospitals, the High Commissioner intervenes directly, or through legal partners. It plays the intermediary to ensure the documents are returned. In the cases where intermediary proves insufficient, other legal measures are adopted. A warrant is sent, for example, or the case is transferred to a higher authority, such as the Ministry of Public Health, if the perpetrator is a hospital.”

Should it happen that documents are confiscated or held by the authorities, UNHCR assists refugees to retrieve their documents, either by following the established administrative processes, for example, those adopted by the GSO, or through advocacy at the regional or central level, addressing the concerned authorities.

Lacking identity documents poses a challenge to refugees’ access to basic and simple services, and might disrupt their daily routine.

Regarding the education of children whose family documents were withheld, the UNHCR said that children without identity documents can register in schools, provided they have a proof of residence from the mukhtar, or a registration certificate issued by the High Commissioner.

Supported by the international community, other UN agencies, and the civil society, the UNHCR said it sustains communication with the Lebanese authorities to guarantee that Lebanon adheres to its local and international legal obligations.

The investigation team sent the General Directorate of Lebanese Security an email through its official address, copying the human rights directorate and organizations, as well as the immigration directorate, but the emailed entities did not respond. The email inquired into the General Security’s reasons for confiscating the Syrian refugees’ official documents; the requirements refugees must follow to recover these documents; whether the General Security facilitates document reclamation for refugees wishing to travel abroad, or provides them with alternative documents that grant them access to hospitals; or helps them register vital civil events, such as births; marriages; and divorces.

Meanwhile, Amina still waits anxiously to retrieve her documents and meet her son, who has been living away from her for years. Hassan, for his part, hopes to reclaim his documents to register his marriage and add his son to the civil records, so he would obtain an identity document, and never have to live on the margins of life like his parents.

This investigation is hosted by the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), and Accesses Center for Human Rights, while funded by Free Press Unlimited (FPU), and published in Daraj Media.

Contributors to investigation and data collection are Marielle Hayek, a human rights researcher, and Eid Al-khoder, a human rights activist.